|

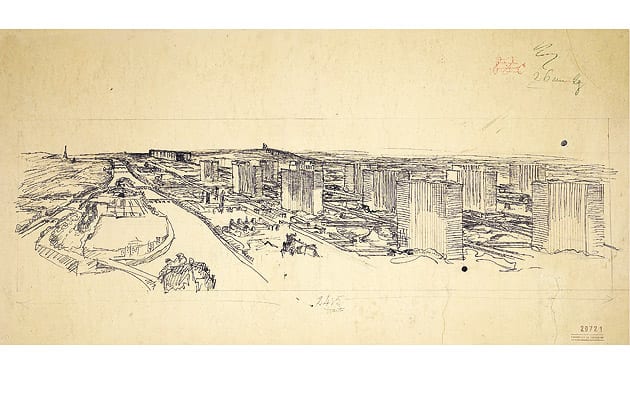

Drawing of Corbusier’s “Plan Voisin” for Paris, 1922 (image: Fondation Le Corbusier) |

||

|

The Picasso of architecture, the poet of the right angle, the Swiss psychotic … Charles-Edouard Jeanneret had many faces, now explored at the Barbican. Owen Hatherley explored the legacy of a busy life. In 2005 I took part in a head-to-head debate on “the legacy of Modernist architecture” at a political conference. I was arguing “for”. To my opponent, a Scottish architect, my citations of Bruno Taut and Berthold Lubetkin were irrelevant. Modernism was fundamentally about the baleful influence of one man: Le Corbusier. When he began by describing him as a “Swiss psychotic”, it was obvious this was not going to be subtle. Some will perennially blame Charles-Edouard Jeanneret for every under-serviced tower block, but the many discussions of Le Corbusier: the Art of Architecture – now at the Barbican, after a spell in Liverpool – have shown the solidification of a common-sense consensus. It is customary to divide his work into three facets – the city plans and collective blocks (mostly bad and “totalitarian”), the purist villas (good, albeit disturbingly bare and technocratic) and late expressionism, especially the Ronchamp church (unreservedly good, the work of a genius – the “Picasso of architecture”). This reflects neatly how architecture is perceived today – the Modernist notion of the architect as improver of mankind’s lot is replaced by the superstar designer of three-dimensional logos. Le Corbusier was unquestionably adept at that, from the trademarked Modulor Man to the Chandigarh Open Hand, now a city emblem used as a stamp on the local driving licences. By presenting an all-encompassing exhibition of the architect as Renaissance man, The Art of Architecture might seemingly offer a corrective to these pat divides. Here is a highly un-purist mass of stuff – models, paintings, magazines, films, chairs, found objects, plans, adverts, saucy postcards. Yet this chameleon and dialectician can’t quite be united into a consistent whole, and the last thing you will find here is “development” in his work, ever progressing and refining itself (as one might in an exhibition devoted to, say, Mies). Instead there are breaks and ruptures. One would have to have absurdly catholic tastes to approve of everything, and only the most dedicated architectural neocon could hate it all. If there is any narrative here, it runs from an early immersion in a Mediterranean Classicism, to the right angles and urban visions of the 1920s, a brief flirtation with constructivism, and then from the mid-1930s onwards, an increasingly organic conception of form. You could pleasurably lose yourself in the density of these artefacts, although it would help not to have been to many exhibitions in the last few years. Films of the Plan Voisin, Villa Savoye or the Philips Pavilion are pretty familiar from the Modernism and Cold War Modern shows at the V&A, as are some of the models. Some of these are successful in their own right as speculative sculptures – a wood mock-up of a projected skyscraper for Algiers, the frame of a Unité’s “bottlerack”. The “art” is diverting, but mainly worthwhile for the insight provided into the architectural designs – his adoring, post-purist sketches of Rubensesque women are more interesting as prototypes for his post-piloti “thighs” than as works in their own right. One section is named Privacy and Publicity after Beatriz Colomina’s excellent book – aptly, as we survey in these vitrines copies of his voluminous printed works, the detritus of a relentless self-publicist, overwhelming as his ego. Nonetheless, in the face of all this eclecticism, we should really have to choose one Le Corbusier. If so, I choose the architect who thrived on the most intense intellectual frictions, and who has the least current influence: the Corbusier of the La Tourette Monastery, of the public buildings for Chandigarh, or of the several Unités d’Habitation. That is, the architect who transformed buildings for communal life from mere filing cabinets into structures of raw, practically sexual physicality, then forced these bulging, anthropomorphic forms into rigid, disciplined grids. This might be the work of the “Swiss psychotic” at his fiercest, but the exhibition’s setting, the Barbican – with its bristly concrete columns and bullhorn profiles, its walkways and units – proves that even its derivatives can become places rich with perversity and intrigue, without a pissed-in lift or a loitering youth in sight. Unlike Ronchamp or Savoye, these collisions of collectivity and carnality have no obvious successors today.

|

Words Owen Hatherley |

|

|

||

|

Assembly building, Chandigarh, India, 1955 (image: Fondation Le Corbusier) Le Corbusier: The Art of Architecture is at the Barbican, London, until 24 May |

||