|

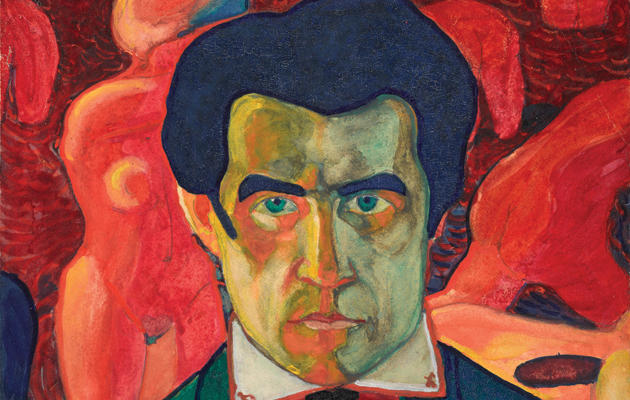

Self Portrait, 1908-10 |

||

|

Tate Modern’s retrospective captures the exuberance of an artist too busy running his own revolution to be tied down by party doctrine, finds Agata Pyzik How do you defamiliarise the avant-garde once it has become familiar? The question has been at the heart of recent retrospectives in London of the giants of modernism, such as Matisse, Mondrian and Malevich. Each of them changed ways of seeing in the 20th century, but perhaps Kazimir Malevich did so most spectacularly. This splendid show at Tate Modern brings together his greatest work from collections all over the world, but the man remains as enigmatic as his most famous painting, Black Square. Malevich remained an outsider to most of constructivism, but because of the full-on qualities of his abstraction he has become the most famous exponent of the utilitarian avant-garde. He was at once the charismatic sectarian leader of the suprematist tribe at the school of UNOVIS in Vitebsk, an author of theosophic treatises who was convinced of his own artistic genius, a faithful supporter of the communist party and the maker both of propaganda for workers and of seemingly more casual film posters. The early art nouveau work may surprise those familiar with Malevich’s ultra-abstraction. It was influenced by a particularly murky form of Jugendstil, full of demonic self-portraits and femmes fatales. Inspired by socialism and wanting to create something more authentically Russian, his canvases came to be populated by increasingly extraterrestrial peasants. His early fauvist compositions become more minimalist and ordered – and acquired a fluorescent colour palette. Scythe (1912) shows this transition from dark, nihilist colours into bright, ecstatic, optimistic ones. From then on, until roughly 1915, Malevich underwent a spiritual, cosmic journey towards suprematism, turning into a shaman of abstract art. He conceived his first version of Black Square as early as 1913, but didn’t paint it until two years later.

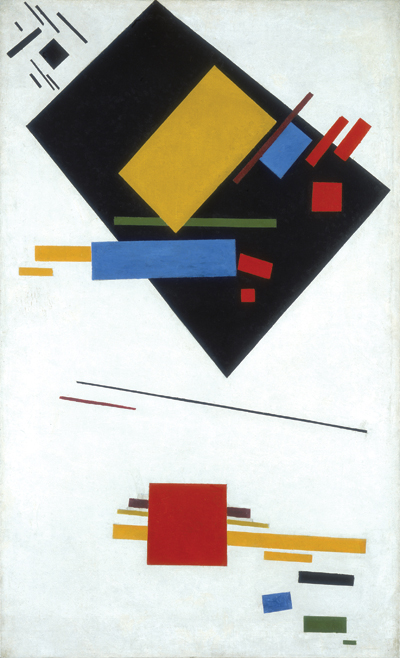

Suprematicist Painting (with Black Trapezium and Red Square), 1915 As with many great ideas, there’s no explanation for this new vision. In The Total Art of Stalinism, art historian Boris Groys quotes Malevich saying: “I have destroyed the ring of the horizon and got out of the circle of objects.” What if creating new worlds may require such Nietzchean convictions? (It wouldn’t be the first time communism has been interpreted in terms of religion.) After Malevich declared painting “dead” in the new post-revolutionary society, he embarked on his Architectons. These fascinating objects combined elements of sculpture, proto-conceptual art and the architectural model, projecting new worlds of divine dwelling. He was inspired in part by American skyscrapers but his ideas were taken up only later by others: by Mies van der Rohe and in brutalism (compare the relentless angles of Denys Lasdun’s National Theatre). At the same time, his painting dissolves into infinitely subtle shades, pointing to the work of Gerhard Richter – and even the likes of the Slovenian avant-garde music group Laibach. One of the reasons Malevich keeps resonating is his popularity among the punk subculture. The costumes for Victory Over the Sun (“the first Futurist opera”) today look more Devo than Bolshoi, and the rip-offs of his designs In response to the introduction of socialist realism (“socialist in content, national in form”) in the early 1930s, he created a new kind realist painting that had more in common with Soviet pop art of the 1970s and Moscow conceptualism of the 1980s than with the 19th-century realism of Ilya Repin. It was an almost ironic take on the requirements. Borrowing from Piero della Francesca or Botticelli in his portraits of peasant girls, workers or his own wife, he never stopped being a suprematist, with a little black square logo and suprematist badges visible on the lurid Renaissance gowns. |

Words Agata Pyzik

Images: Tate Modern; State Tretyakov Gallery

Malevich: Revolutionary of Russian Art |

|

|

||