|

|

||

|

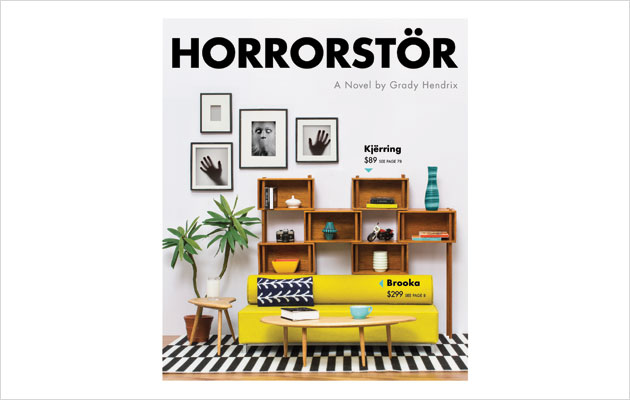

There’s something nasty in the flatpack furniture store … Will Wiles enjoys a ghost story with a truly sinister setting Orsk is “the all-American furniture superstore in Scandinavian drag, offering well-designed lifestyles at below-Ikea prices”, with 112 locations in North America and a further 38 across the world. “Our focus here is aspiration, not acquisition,” says Amy, an Orsk “floor partner” as she shows new recruits around location #00108, Cuyahoga County, Ohio. “We want to teach customers how elegant and efficient their lives can be if they’re fully furnished with Orsk.” But all is not well at the Cuyahoga Orsk. There has been a spate of petty theft and vandalism, apparently occurring at night. The giant store, built on a reclaimed swamp near the freeway, has failed to thrive in the six months since its opening. Consultants are coming from the corporate headquarters in Milwaukee. Amy fears for her job, which is why she agrees when her pedantic, jargon-spouting boss, Basil – “Way to live the ethos, man!” – asks her to stay back one night in an effort to get to the bottom of the mounting problems. Something is rotten at Orsk, and it’s not the meatballs; it turns out to be far, far worse. Set over the course of that night, Grady Hendrix’s Horrorstör is a ghost story – at times straying into Grand Guignol slasher – set entirely amid the bright colours, cheerful Scandi modernism and sunshiny marketing There are flaws. Characters sometimes act more in the service of the plot than in their own best interests, the kind of non-logic familiar from horror films. But curiously this matters little, as it suits the setting rather well – these places are designed, to the utmost degree, The store induces “Gruen Transfer, a sense of confusion and geographic despair that keeps you completely disoriented” – this is all perfectly real, named for the architect Victor Gruen, the man credited with inventing the shopping mall. Who needs poltergeists when we’re the lost souls? Given this gift of a setting, it’s faintly disappointing that the evil at large in Orsk turns out not to strictly originate from the store itself – as it should do in a completely modern horror – whatever inventive uses it makes of its new home. But, again, the potential misstep is salvaged as Hendrix explores the similarities between modern retail and more ancient, darker practices. Are they really that much darker? Amy and her colleagues are trapped in the store because they are trapped in their jobs, jobs they can’t afford to lose, so they can’t afford to tell their boss to stick his sleepover, and even he’s trapped, with those consultants closing in like the encroaching shadows. Ghastly precarity infects all their actions. The most horrible moment comes when the aspirational illusions of hard-work bullshit and false hope are peeled away and Amy is given a glimpse of, not the skull beneath the skin, but her actual economic predicament. We could do with a lot more horror like Horrorstör, set among the dreamworlds of 21st-century capitalism; so-called realist fiction isn’t really paying attention. |

Words Will Wiles

Horrorstör |

|

|

||