|

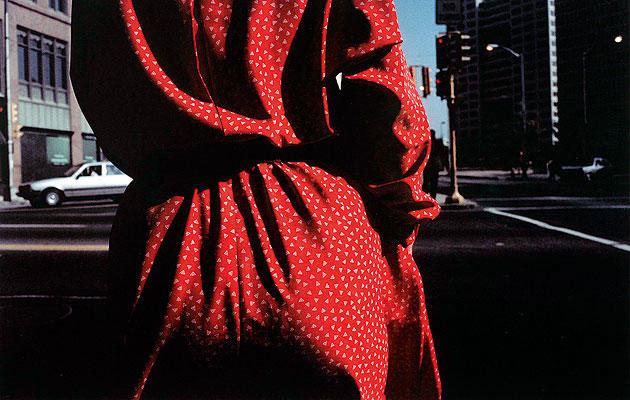

Untitled (Atlanta) by Harry Callahan, 1984 (image: © Estate of Harry Callahan, Pace/MacGill Gallery) |

||

|

Illicit photography makes a magnificent theme and the Tate brings us every bedsheet and bloodstain. William Wiles had a good look Lovers copulate in an urban park. Around them, voyeurs gather, crawling over the grass, sometimes in their underwear, sometimes close enough to the action to lay a hand on a buttock. The coarseness of the black-and-white images suggests nature photography – there is a sweaty, animal tang of predation. Are the lovers aware of the watchers? How could they not be? Are the watchers aware of the photographer, Kohei Yoshiyuki, watching them? And behind the photographer stand us, the audience in Tate Modern, admiring Yoshiyuki’s 1971 photo series The Park. We are all involved, all implicated in the grass-stained fucking. Indeed, when Yoshiyuki first exhibited The Park, he did so in a darkened room and gave flashlights to the visitors, just to make the connection clear. This sense of involvement pervades Exposed, Tate Modern’s enormous summer exhibition devoted to photography of unwilling or unaware subjects. Few shows so effectively entangle the visitor in their subject matter. You are there to look – to look at the women in the street, the backroom smut, the dishevelled hotel rooms, the mutilated bodies, the secret facilities. Exposed has the sordid air of a suburban orgy – we’re all here for the same reason, and we’re none of us better than the other. The only nobility is maintaining eye contact with other people when you emerge, exhausted and in need of a good shower, into the gift shop. And it is exhausting. Exposed is colossal, divided into 14 rooms covering five topics, each of which could have made a decent exhibition on its own: the unseen photographer, voyeurism and desire, celebrity and the public gaze, witnessing violence and surveillance. On the bank holiday weekend that icon visited, it was thronged with looky-loos; Nan Goldin’s slideshow The Ballad of Sexual Dependency and the room filled with death camps, lynchings and assassinations were particularly crowded. People clearly like to look. The ambition of the curators can’t be faulted – Exposed brings together a roll-call of 20th century photography, united under a bold, timely theme. It is encyclopedic and as such defies criticism other than to complain that there is just too much. What’s most interesting about it is that the theme is perennially relevant. Even after 150 years, photography remains a disruptive, dangerous technology – the lens continues to rub sharp edges against soft social tissue, from happy-slapping to surveillance drones. Exposed can be seen as an alternative history of photography, the advance of the camera in the service of human deviancy, the social mutations around the device, like flesh puckering around a cyborg implant. It’s a magnificent show, though highly mixed. The celebrity section is the weakest, reminding us only of the sheer ubiquitous banality of pap pics, a thoroughly debased currency. Surveillance, a vital theme, has the artist mostly at arm’s length, “responding”, not as involved as in other areas. But the show is clearly in its element with candid photography and voyeurism. A history of voyeurism is long overdue – it is participation without participation, the signature perversion of the networked 21st century. We watch and are watched.

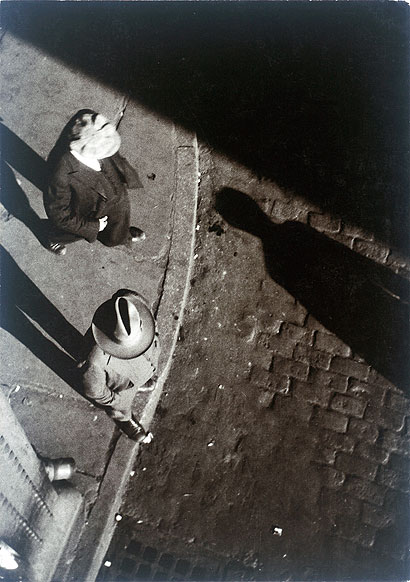

Street scene, New York by Walker Evans, 1928 (image: © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art) Exposed: Voyeurism, Surveillance and the Camera is at Tate Modern, London, until 3 October |

Words William Wiles |

|

|

||