|

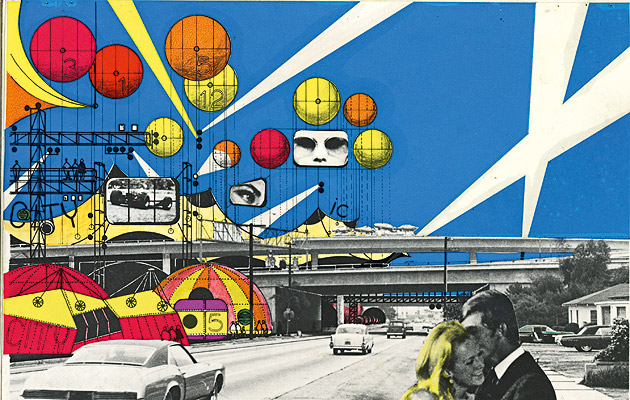

Instant City, Santa Monica and San Diego Freeway Intersection, by Ron Herron (Archigram), 1968 (image: Courtesy of Simon Herron) |

||

|

Lyra Kilston picks over the fascinating relics of an era of LA art and architecture when nobody quite knew which was which “Tip the world over on its side, and everything loose will land in Los Angeles,” said Frank Lloyd Wright. He was referring to the city’s salmagundi of building styles, but a fascinating exhibition at the MAK Center for Art and Architecture at the Schindler House has repurposed the phrase. It looks at LA’s architecture and art from the late 1960s to the early 80s, when the very idea of what constituted “architecture” was also being tipped on its side, as illustrated by Reyner Banham’s book Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies (1971), in which he deemed the intersection of two major freeways a work of art. The disciplines of art and architecture contaminated each other to fascinating ends in an environment rife with visions of ecological doom, technological salvation and radical gender politics. The works are divided into themes of Procedures, Users, Environments and Lumens (works related to light), and it is often indistinguishable which of them are by artists or by architects. Architects were drawing, doing collage, and making sculptures; artists were creating conceptual, ephemeral and even actual buildings. So, displayed near images of artist Allan Kaprow’s Fluids (1967), in which several house-sized structures were built of ice blocks and left to melt, is an issue of Leonard Koren’s Wet magazine, a publication devoted to “gourmet bathing” that he submitted as his architecture thesis project. The exhibition snakes through the rooms and gardens of the 1922 modernist residence by Rudolph Schindler. The house is used to ideal ends in the Lumens section, where translucent Light and Space-era sculptures by Peter Alexander and Larry Bell occupy Schindler’s glass-walled corner, along with Frank Gehry and Richard Serra’s wood shelves with transparent fish scales. All of these objects allude to the region’s clear and perpetual light, which has influenced its artists and architects over the past century. An astounding selection of rare archival material makes up the bulk of the exhibit; with so much ephemera and documentation, context is crucial. Each section is accompanied by a pamphlet, and the relics occasionally pale beside their back stories. Nearly every object possesses a cultural history warranting its own small monograph. For example: a film about the 1970 mirror dome shown at Expo Osaka, built by EAT (Experiments in Art and Technology), which tried unsuccessfully to graphically veil its corporate sponsorship by PepsiCo. Or drawings of the giant floral highway signage by Venturi & Rauch with Denise Scott Brown for an ambitious desert city that was meant to rival Los Angeles but ended up unable even to populate its original street grid. Some of the projects on view are surprisingly prescient, depicting what we would today call “smart” architecture or augmented reality. A poster for the seminal 1969 Art and Technology exhibit at Los Angeles County Museum of Art shows the museum with a huge electrical plug emerging from its side. Portable Person (1973), by Robert Mangurian of StudioWorks, is a photocollage depicting a life-sized human who has been artificially enhanced with sensors, antennae and cameras. There’s also UniverCity Now (1967) by Craig Hodgetts and Keith Godard, anticipating a “total experience in multimedia teaching”, in which every lecture could be broadcast live and watched on multiple screens. (Today’s Google Glass and open online college courses don’t seem quite as innovative now.) Architect Neil Denari has characterised the era as a meeting of “the hippie and the astronaut”. The aims were lofty, the technology intoxicating and experimentation trumped production. This sea change wasn’t limited to LA of course; in 1980 architects were formally included in the Venice Biennale for the first time. But due to its unconventional urban scheme, its inescapable signage and dominant media, LA became an important source for conceiving of architecture in new ways. As this exhibition proves, incredible things occur when disciplines get loose.

Instant City, Santa Monica and San Diego Freeway Intersection, by Ron Herron (Archigram), 1968 (image: Courtesy of Simon Herron) Everything Loose Will Land, MAK Center, Los Angeles, 8 May – 4 August 2013, Yale School of Architecture, 28 August – 9 November 2013 |

Words Lyra Kilston |

|

|

||