|

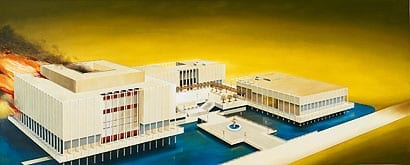

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art on Fire, 1968 (image: Ed Ruscha, 2009 with photography by Paul Ruscha) |

||

|

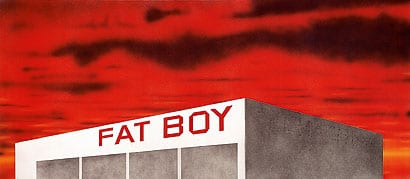

It’s hard not to see this seminal artist’s work as a celebration of ephemeral America – but these days its glamour is less obvious. Mark Rappolt looks back Ed Ruscha’s 1979 work I Don’t Want No Retro Spective was proudly displayed on the cover of a catalogue accompanying a San Francisco retrospective of the Los Angeles-based artist’s work in 1982. Now, several retrospectives down the line, Ruscha is at the Hayward. I Don’t Want … isn’t, however. Not because, all these years and exhibitions later, it seems like a tired joke; but rather because this show is exclusively about paintings (five decades-worth no less), which means no pastels, no photographic or graphic design and no book projects. On one hand this is a shame, because projects like Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966), in which the artist photographed everything promised by the title and then laid it all out as two facing parallel strips on a continuous sheet of paper (folded accordion-style into book form), with a blank space in the middle where the road should be, seem as important to understanding Ruscha’s work and its significance as anything on show here. But on the other hand, Ruscha’s painted output is more than meaty enough to satisfy even the most carnivorous of culture vultures. If Ruscha has a “signature” motif, it lies in his use of text as and in image. You could view it perhaps as a sort of high-end graffiti – the last works in this show, Azteca and Azteca in Decline (2007), suggest that reading. In conversation, Ruscha refers to the texts in his paintings as a kind of architecture, in the sense that they are signs with a more-or-less visible structure attached. This is more the case with something like The Old Tech Chem Building, a rust-belt warehouse with the words Fat Boy written on the facade; and less with a work like OOF (1962), written in yellow on a blue background, giving it something of a Swedish feel – perhaps randomly, for one of the games these works play with the viewer involves an oscillation between meaning and meaninglessness. On the one hand, in a work like OOF, we’re confronted with a word stripped back to its muted essence; on the other hand, there’s a sense in which such works, in spite of their apparent minimalism and simplicity, become the setting for a positive orgy of ornament (the sound of the word running through your head, the colours, the choice of font, the backdrops). Similarly those absent photographic projects make you fully conscious of every minute embellishment a Sunset Strip shopkeeper adds to their premises. Perhaps the best-known work in the show is Standard Station (1966), in which the petrol station is given a similar graphic treatment to the 20th Century Fox logo. At the time Ruscha made the work, gas stations symbolised modernity and the apparent freedom of the road; now they are part of a dialogue involving Gulf Wars, environmental catastrophe and some of the more sinister vested interests of multinationals, that their creator certainly didn’t have in mind when he painted them. Is Ruscha aware of this? There are certainly moments of sombreness and sobriety as you go through the upstairs rooms (and later works) of the exhibition. There are black-and-white meditations on religion, sin and death (Ruscha had a strict Catholic upbringing); the experiments with juxtaposing text against a landscape (which by the standard set by OOF seems a little like cheating, or acknowledging a failure in his representations of words “on their own”) and extracts – in the form of the Tech-Chem paintings, from Course of Empire, Ruscha’s brilliantly subtle critique of modern America, first shown in the American Pavilion at the 2005 Venice Biennale. For all that Ruscha celebrates the ephemeral architecture of gas stations and the freedom delivered by the automobile, what this exhibition ultimately demonstrates is that these things are trapped in a particular moment of time. (Incidentally, Ruscha has painted a large number of years – in their numeric form – over the, um, years.) So what about Ruscha and retrospectives? Maybe, after all, the key is in that absent work: I Don’t Want No Retro Spective, a double negative that suggests that Ruscha does in fact want a retrospective, even though the American vernacular indicates that the artist does not, in fact, want one after all. It’s that embrace of opposites, with equal measures of humour and despair, that makes Ruscha one of his generation’s most important chroniclers of modern American life.

The Old Tech-Chem Building, 2003 (image: Ed Ruscha, 2009 with photography by Paul Ruscha)

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art on Fire, 1968 (image: Ed Ruscha, 2009 with photography by Paul Ruscha) Ed Ruscha: Fifty Years of Painting is at the Hayward, London, until 10 January 2010 |

Words Mark Rappolt |

|

|

||