|

The Georgian period is by far the most popular (image: Lee Kirby at Kensington Dollhouse Festival) |

||

|

Will Wiles marvels at the art of domestic bonsai – even if it is all a bit upstairs-downstairs I remember the food. My grandmother had a few Edwardian dolls’ house bits and pieces that had survived decades of aggressive fondness from generations of my family. The furniture I can’t recall, but the food: a tiny plaster smoked salmon, plaster blancmanges and hams and cheeses, some attached to silver plates that also bore tiny knives. There was something about it that invited wonder. The interest was passed down to my mother, who made dolls’ houses for my sister. When my first novel was published, my mother gave me a diorama of one scene rendered in dolls’ house furniture. Dolls are, of course, for girls. Dolls for boys aren’t called dolls, they’re called action figures, figurines, models, anything else. The interest in teeny-tininess is gender-blind, even if zombie cultural momentum streams the girls into home-making and the boys into war-making. All children are drawn to scaled-down versions of the world they can deal with on more equal terms than the grown-up reality around them. A young boy equipping a party of hobbits or a platoon of space marines has more in common with his dolls’-house-owning sister than he might care to admit. This demographic imbalance can be seen at the Kensington Dollshouse Festival, which one November day a year fills the Royal Borough’s town hall with extravagant teeny tininess. The punters are overwhelmingly women, mostly older women. Behind the stalls, however, the genders are more in equilibrium, perhaps even tilting the other way, suggesting that in designing, making and selling, men can exercise a fascination with domestic bonsai in a culturally acceptable way. And it’s such fascinating stuff. Danny Shotton specialises in 1:24 scale tools: handsaws, mortars and pestles, carving knives, pokers. Wherever possible, he keeps to the materials used in the real thing: his steel cutlery has ivory handles recycled from piano keys. Dateman Books prints “readable” copies of Dickens, Austen, HG Wells et al the size of postage stamps – “readable” in quotes because the infinitesimal text is murder on the eyes. But you know it’s there. Aidan Campbell paints reproductions of great works of art the size of passport photos, and enjoys commissions: he reproduced Hans Holbein’s Henry VIII with the face of a client’s grandfather. You can almost feel the humidity around the Miniature Garden Centre’s verdant display of paper houseplants and greenhouse exotica. Again, however, it’s the food that really takes the breath away. Minicaretti, an Italian studio, makes biscuit boxes with individual biscuits in a little tray inside. Pride of Plaice, as the name suggests, produces mini-fishmongery, but also heaps of delectable miniature groceries. Platts Mini Packages does dry goods: bright boxes of breakfast cereal, confectionery and washing powder laid out in an Andreas Gursky-style blaze of abundance. What makes the food so appealing? Perhaps it is the playful, paradoxical artifice of anything that has been made to look consumable, but which we know is not. The dolls themselves are scarcely to be seen. They are nothing more than surrogates for all this nano-consumerism, anyway, ciphers on to which all this desire can be projected. It’s a good thing too, because in their stuffy Victorian dress or maids’ uniforms the dolls are a reminder of the truly embarrassing feature of the world of dolls’ houses: the fact they tend to be so reactionary, a world of mistresses and servants, upstairs-downstairs, Downscale Abbey. They don’t have to be, of course, but it’s very noticeable that (a few white goods aside) the latest furniture is from the 1930s and the most recent style is art deco. The only modern building I saw was the London Eye, which appeared as part of a miniature London teapot and can hardly be said to count. What’s the most popular style, I asked a designer of bespoke dolls’ houses. “Georgian,” she answered without hesitation, with total certainty in her voice. “I suppose it’s what people dream of.” Did she ever get asked for a more modern style, something post-1914? “I’d love to be asked to do that,” she said with some fervour. “Art deco … The Shard … ” All the world of dollhouses needs is some enlightened clients.

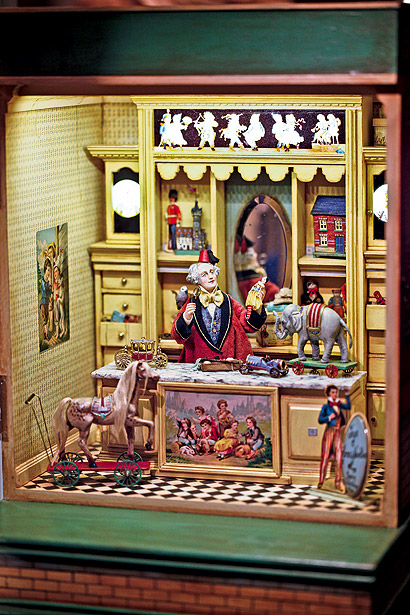

A 1:12 scale interior by Gale Elena Bantock (image: Lee Kirby at Kensington Dollhouse Festival)

The Georgian period is by far the most popular (image: Lee Kirby at Kensington Dollhouse Festival) Kensington Dollhouse Festival, Kensington Town Hall, London, 30 November 2013 |

Words Will Wiles |

|

|

||