|

|

||

|

If the semiotic scattercast of Danny Boyle’s 2012 Olympics opening ceremony proved anything, it’s this: James Bond remains central to Britain’s national imagination. Peter Pan and Tim Berners-Lee didn’t get equal billing to the Queen. But there was Daniel Craig, Bond’s present vessel, with Her Maj herself, sharing with her a continued non-obsolescence that is equal parts mystifying, frustrating and marvellous. Now portrayed by half a dozen loyal subjects over the course of a round half-century, Bond is more idea than man – a set of tropes, traits, togs and toys, flexible, fun and repellent, swaddled in the highly distinctive anonymity of the world’s most famous codename, 007. This interchangeability, the near-irrelevance of the actor in the role (though they all have their merits and demerits), makes Bond a kind of design object himself, a dark instrument, a post-imperial fantasy of global power-projection. A weapon, a drone strike in a dinner jacket.

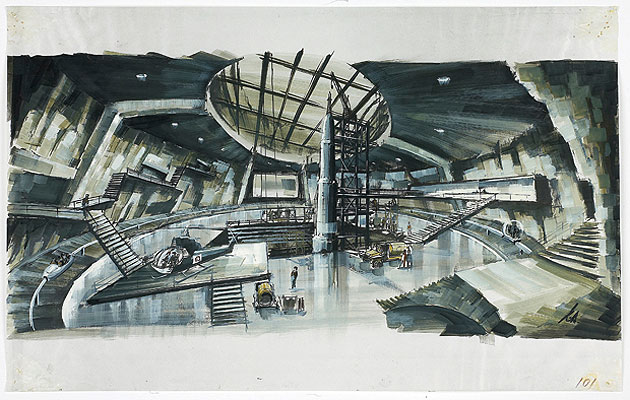

An examination of Bond design and style is, then, a fundamentally good idea. Designing 007 might sound like Olympic summer tourist-bait … well, yes, it’s very much that as well. This sprawling exhibition, split over three parts of the Barbican, at points feels fluffy indeed. Some of the artefacts would surely be more at home in a lesser branch of Planet Hollywood. Albert R Broccoli’s Irving G Thalberg award (no, me neither). A reproduction of Honor Blackman’s golden leather jerkin from Goldfinger – presumably the Louvre wouldn’t loan the real thing. A cast of Electra King’s ear. Copious screens play clips from the movies, with the not wholly desirable side-effect of making me want to go home and watch the movies. Some captions are less than edifying. “Location scouting for Bond involves combing the globe in search of visually interesting places which suit the story” – yes, I imagine it does. But these low points are easily skipped over, like the weaker films, and like the franchise the rest of the exhibition is straightforward amoral fun. Ian Fleming, whose novels created Bond, is given obeisance with a recap of his fascinating life and a display of first editions with splendid covers by Richard Chopping. Then you can forget that there were any books as the movies take total control. Oddjob’s razor-brimmed bowler hat! The metal false teeth that turned Richard Kiel into Jaws! Honey Ryder’s bikini! A Y-chromosome does assist appreciation. The Piranesian scale and gloom of the set designs of Sir Ken Adam are the dominant architecture at Designing 007. But there are some beautiful original paintings for some other memorable interiors, such as Peter Morton’s ideas for the tilted MI6 offices aboard the grounded liner RMS Queen Elizabeth (getcha post-imperial metaphors here) and Harry Lange’s constructivist space station for Moonraker. There are a lot of costumes, probably too many. Casino and Ski sections may provide swigs of the 20th-century idea of glamour but feel padded out with too many uninteresting gowns, tuxes and tracksuits; the gallery on villains and Bond girls is much better.

As with the films, Q Division provides a good portion of the entertainment value and allure. Based on Fleming’s experience of Britain’s wartime Special Operations Executive, which flung exploding rats into the Nazi war machine, Q Division provides Hasselblad cameras that turn into rifles, amphibious Lotus Esprit sports cars and a Swaine Adeney Brigg briefcase that sprouts a dagger. Bond likes his toys classy, and the films have an eye for high-end design. Scaramanga’s golden gun, from the eponymous film, was developed with luxury accessories brand Colibri; a caption elsewhere intriguingly hints that the trend for deluxe technology is presaged by Bond’s disguised gizmos. Or did Bond perhaps contribute to that trend? Designing 007 is summertime escapist larks, but more than once I found myself hankering for some deeper context and analysis, including some idea of the influence of Bond outwards, on to design. One can’t help but suspect, for instance, that the puerile gold-plated guns and shag pits of Saddam, Gadaffi and their ilk owe something to Bond’s conscience-free exercises in wish fulfilment. |

Image Danjaq, LLC and United Artists Corporation, 1962; 1967; 1974

Words Will Wiles |

|

|

||