|

|

||

|

An unconventional procurement and curatorial process by France’s centre for contemporary art has resulted in an exhibition that critiques material culture by juxtaposing related objects, says Peter Maxwell The Centre National des Arts Plastiques (CNAP) is a body responsible for France’s contemporary art collection, an archive that contains 95,000 works, 6,5000 of which come under the moniker of design. Often referred to as a museum “without walls”, this repository has no dedicated display space, instead focusing on collaborating with external galleries through loan or exhibition to make its catalogue available to the public. CNAP’s procurement policy is somewhat unique: it has no interest in establishing a form of disciplinary canon, nor is it the mere representation of the tastes of the various heads of department. Instead, new works are nominated by an invited panel and then subjected to an intense round of debates (seemingly not unlike an art school crit), with staff having to actively argue for or against each piece’s inclusion. This fiercely democratic methodology has created an eclectic picture of contemporary design, one that places the emphasis solely on the merits of each individual entry. The lack of a guiding principle means, however, that the role of unpacking the collection for the public requires deft programming. A powerful example of this is the current Comfort Zones exhibition hosted at the Galerie Poirel, Nancy, which runs until 17 April, curated by Juliette Pollet, head of CNAP’s design and decorative art division, and Studio GGSV. Their solution has been to create a form of immersive promenade theatre using 101 items from the collection. The long galleries at Poirel are thus divided into four acts – the office, the reception, the play area and the antechamber – that form the imagined habitat of a capricious collector. Key to this is the GGSV-designed scenography, which centres on a bespoke carpet that uses graphics to mark the transition between zones while eliminating the need for many physical barriers. The carpet’s secondary role, through its use of cosmic imagery, is to act as an metaphor for the audience’s leap of faith, to follow the curators in placing the exhibition’s contents in a context free from established biases. The title of the exhibition is double-edged, intended to skewer the preconception of design as a form of material sycophancy, the provision of a frictionless, unchallenging environment. Indeed, both Pollet and Stéphane Villard (one half of GGSV) explain part of the impetus behind Comfort Zones as being a lack of a notion of the “critical” potential of design within French culture.

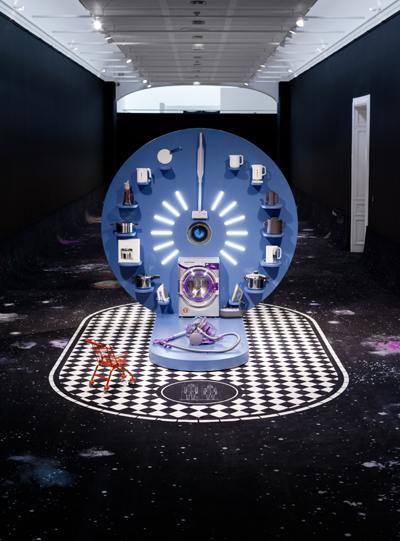

In concept Comfort Zones is not too distant from the 2013 V&A exhibition Tomorrow, conceived by artists Elmgreen & Dragset, which also looked for new means to decode a large design archive. That exhibition took the form of the fictionalised apartment of an elderly architect, using items from the museum’s extensive collection for furnishing and decoration. The difference between the two is that Tomorrow subsumed everything beneath a narrative realism so complete that objects lost all personal definition. Comfort Zones’ fiction is more clearly an organising principle, a mechanism used to raise specific questions and bring different works into relation without occluding the audience’s ability to appreciate their individual merits. The first tableau, a pinwheel of kitchen utensils, demonstrates this immediately. Design’s claim to social relevance is so often undermined by institutional bias towards the thin, gilded end of its spectrum – the short run, artisanal or crafted product of a few feted studios – while failing to sufficiently interrogate the largely quotidian nature of the discipline, that which actually gives it legitimacy. The curator’s begin the rapprochement by offering for formal comparison items such as Gaetano Pesce’s overwrought cafetière Vesuvio and Ineke Hans’ Black Gold Collection teapot, two essentially ornamental objects, alongside an array of mass-produced kitchen gadgets that – while still the creation of names such as Jasper Morrison or Marc Newson – privilege the sort of (untitled) work that you might buy from your local hardware store. This elevation of the domesticated over the rarefied object in design is heightened by the inclusion of two early products from James Dyson’s stable, products that, whether you liked them or loathed them, set a new level of aesthetic ambition for “white” goods.

The following Reception area has, to use GGSV’s own terminology, the appearance of a sofa “car park”, the intentionally cramped layout providing an overview of our changing attitudes to posture – while you might have posed in Eero Aarnio’s 1967 Pastel Chair or slumped in Michel Ducaroy’s 1973 Togo banquette, Maarten Van Severen’s 2000 MVS chaise longue allows reclining only at its most precarious, while Francesco Binfaré 2011 Sfatto sofa has such a grotesque aura that it dissuades sitting entirely. The show eschews any form of gallery text in favour a more direct confrontation between audience and object, though it can’t fully address the perennial problem of the design exhibition: a lack of physical interaction with products that are only fully understood through use. This is somewhat offset in an “intermission” area that allows you test some examples of the furniture on display.

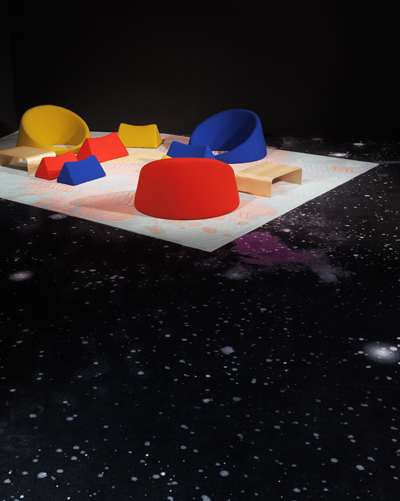

The Play area, alternatively, contains objects whose uses are less clearly defined, instead posing the question of whether ambiguity, and thus freedom of interpretation, might be of greater comfort to the user than functionalist prescription. Here we are presented with conspicuously hybrid objects, such as Bless’ Mobile#1, a desk-come-cabinet suspended so that each use counterbalances the other, leaving it largely inoperable; or Nanna Ditzel’s abstract Winkel og Magnussen, a form of furniture so reductive that trying to arrange yourself between its brightly coloured supports creates a game out of inactivity. This grouping also contains a variety of experiments in consumer electronics that tried to divert from the push-button black-box paradigm still largely in operation today. Products from the likes of Tim Thom, such as the 1995 Boa, a leather scarf weighted with speakers – a humorous take on the ghetto blaster – mark an era in which designers were first trying to convince industry of the worth of conceptual design as means of humanising technologies sharp edges. The finale of this four-act drama is the antechamber, a small room typically used to prepare the visitor for whatever may happen in the adjoining, more significant space – in this case that which the audience return to on leaving the gallery. A dinner table is ringed by chairs and arrayed with objects as if for a dinner party, though the mood is one of anxiety. For Pollet, comfort’s contemporary condition is that of existential risk management, the realisation that technological progress has given us little mastery over nature only heightening the desire to “control (our) environment”. Cloning and genetics comes to fore in the work of 5-5 Designers, whose furniture is both a literal and figurative dissection of the human body, and in another Stark work, Teddy Bear Band, a kitsch yet horrifying animal Frankenstein.

It is here that Comfort Zones’ trick of criticism through association truly gains traction – Sony’s familiar AIBO robot dog is now transformed into an uncanny marionette, while the Bouroullecs’ Workbay chair, perhaps innocuous on its own, sees its “privacy” hood rendered as ghoulish cowl. Even Mathieu Lehanneur’s Andrea air purifier, essentially a pot-plant bio dome, becomes an image of entrapment and suffocation. In comparison to the static, historically linear displays through which most institutional design collections are communicated, CNAP’s jigsaw-puzzle approach looks eminently more capable of provoking both its audience, and its objects, to question the current state of the discipline. |

Words Peter Maxwell

Comfort Zones |

|

|

||

|

|

||