|

Protestors on scaffolding tripods designed to prevent removal by police (image: © David Levene/Guardian News & Media Ltd 2009) |

||

|

More than just a protest, the Climate Camp on London’s Blackheath was a proposal for a changed, healed world. It might be different to Canary Wharf, says Owen Hatherley, but is it really any better? On an August bank holiday there are a few possible uses for a heath. At a corner of Blackheath, at the point where the greenery fades into the messy urbanism of Lewisham, is the Climate Camp, watched over by police and a cheekily opportunistic ice-cream van at one end and a funfair at the other. The Camp for Climate Action is an activist group known for its pickets of particular sites where carbon is most likely to be belched into the atmosphere – the site of the Heathrow expansion, the Kingsnorth Power Station. But its pickets aren’t solely about protesting and then going home, but rather they try to carve out some sort of oppositional, independent space. Whether consciously or not, the Climate Camps are an echo of the idea of the “temporary autonomous zone” popularised by 1990s cyber-theorist Hakim Bey. The “TAZ” is a term usually used in the context of raves or more politicised actions such as Reclaim the Streets in the late 90s – immediate, participatory events. Yet the Climate Camp is deeply media-conscious, aware of the need to broadcast outside of that “zone”, as was obvious at its camp against the G20 meeting on 1 April this year – while crusties smashed up banks half a mile away, it made sure the image of its event that made the news was peaceful campers with their hands in the air chanting “this is not a riot” while being attacked by riot police. In Blackheath, picketing nothing in particular, the camp becomes a demonstration of itself, a discussion space aimed at the metropolitan public, deliberately drawing attention to itself as a temporary autonomous zone – even if it is fenced off both from the police, and inadvertently from this (well-heeled) corner of south London. What’s interesting about the Climate Camp is its interest both in protest and in proposing another way of living. In a time when utopianism of any sort is thin on the ground – other than as an object for nostalgia – this alone makes them worth taking seriously. Many gathered on Blackheath claim that the camp itself provides at least a potential model of a post-carbon, post-growth world. So what is it like, this new world? Well, it’s very well organised indeed, clean and civilised. The mayor of Lewisham haplessly moaned that “taxpayers” would have to clean up after the camp, while in reality the campers were even picking up the KFC boxes and used condoms on the areas of the heath they weren’t occupying. There’s a lot of talking, yet nobody is being lectured – there’s much debate, especially over whether “technofixes” or “lifestyle” are the best way to adapt to a world without fossil fuels. The rejection of these “technofixes” often means a rejection of modernism. In the leaflet that explains why they chose Blackheath, the campers have as number 1 on the list their opposition to the “Tall Buildings” of Canary Wharf, which the heath overlooks. Their ad hoc, low-rise settlement is the explicit alternative. The main part of the camp is a series of marquees – one showing films, others hosting speakers and seminars, a tent for “tranquility”, another that broadcasts to the outside world, a medical tent and a sound system, all of which use electricity generated on-site. So the camp clearly uses advanced technology, of a sort, with solar panels and laptops in evidence. Yet it’s the low-tech elements that seem most striking. Not only the notorious compost toilets, erected by campers out of wood, with all waste to be re-used as fertiliser (although mercifully they’re for sitting, not squatting), but also a wall on which various slogans are scrawled, and several hay bales, used both at the entrances in case of rain and mud, and more whimsically for seating. That’s before we get to the acoustic guitars and earnest conversations. Though it’s by no means a camp of crusties, an adherent to the modernist ideal of clean living under difficult circumstances might find it all a bit too hairy. It’s easy to miss just how technologically savvy the camp actually is, because their aesthetics make a virtue of necessity. The Climate Camp’s serious politics make it far more worthwhile than, say, EXYZT’s recent Dalston Mill installation (icon 076), and it has aims other than giving green consumers a warm glow of virtuousness. Instead it recognises the need for enormous, structural changes, both in wider politics and in everyday life, and by association, in the way we design our lives. Yet it’s precisely here that the camp is at its most flawed – it inadvertently becomes an aestheticisation of emergency. As a way to support an entire society, rather than a thousand or so campers, the camp describes dystopia, not utopia. There’s an instructive contrast between the goodwill, intelligence and participation in these marquees and the viciousness, atomisation and stupidity that occurs in the glass-and-steel office blocks they look out on. Yet a world run on pedal-powered generators, with no system of drainage, would be nearer to urban historian Mike Davis’ Planet of Slums than the healed planet imagined by some of the campers. What is enjoyable, in fact pretty laudable, in a corner of south-east London would be terrifying on a larger scale.

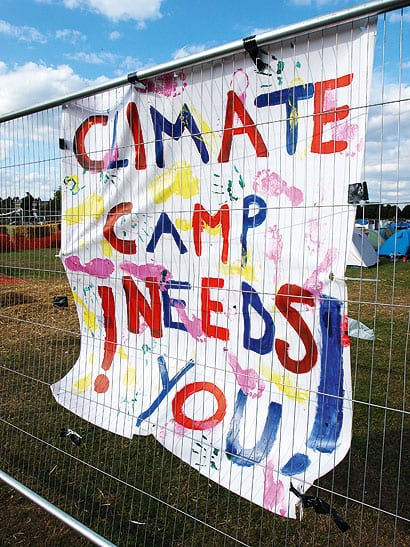

image: © Nina Power

image: © Nina Power

One of the notorious compost toilets (image: © Nina Power)

Protestors on scaffolding tripods designed to prevent removal by police (image: © David Levene/Guardian News & Media Ltd 2009) |

Words Owen Hatherley |

|

|

||

|

A packed talk in a marquee (image: © Nina Power) www.climatecamp.org.uk |

||