Thonet is the furniture company that was modernist before the modernists, and – now in its 200th year – outlasted them all, writes John Jervis

Frankenberg-based firm Thonet will be 200 years old in 2019. It stands alone as the most influential furniture manufacturer both of Victorian industrialisation and of the modernist explosion, producing the two chairs that define both eras. Also, against the odds, it has survived their passing. Forced to rebuild in the post-war years, Thonet pursued an astute course, extracting subtle if pragmatic lessons from modern design’s frenzied birth. Its avoidance of the gravitational pulls that beset the industry – triviality, transience, dogmatism and luxury – is not just good business. It is also good design.

Thonet was founded in 1819, pioneering bentwood furniture using veneers, but in 1856 it patented a cheaper solid-wood alternative. This allowed the manufacture of attractive, lightweight furniture from a limited number of interchangeable parts and used, for the first time, production lines. The most famous example was the No 14 chair, introduced in 1859, known today as model 214. A sturdy yet elegant design, praised by Konstantin Grcic as ‘one of the most beautiful chairs there is’, the No 14 rapidly became indispensable for cafes, restaurants and assembly halls across Europe. Within three years, Thonet needed to build an entire new factory dedicated solely to its manufacture.

Composed of six wooden parts, ten screws and two washers, it heralded a new era of affordability, standardisation, mass production and global trade – a crate measuring just one cubic metre could hold 36 disassembled chairs. Despite losing its bentwood patent in 1866, Thonet flourished to become the world’s biggest furniture company. By the early 20th century, it was bringing leading architects into the mix – Adolf Loos, Josef Hoffmann and Otto Wagner among them – offering almost 1,000 models and producing 1.8 million items each year.

Although weakened by the First World War, Thonet recovered in the uncertain 1920s, thanks in part to the affordability of its products. In addition, a bloc of young architects, many affiliated with the Bauhaus, began to identify in Thonet’s bentwood furniture the simplicity, transparency, functionalism, affordability and absence of ornamentation that they themselves were seeking to achieve. The furniture directly reflected and expressed its material and industrial manufacture, thus gaining an almost spiritual quality for this new sect. In short, they recognised that Thonet had achieved modernism before modernism, and were not shy of saying so.  130 chair by Naoto Fukasawa (2010), one of Thonet’s most successful recent designs

130 chair by Naoto Fukasawa (2010), one of Thonet’s most successful recent designs

Siegfried Giedion described Thonet’s bentwood as ‘form purified by serial production’; Le Corbusier praised its nobility; Ferdinand Kramer called it ‘the quintessence of industrial-economic thinking’. In 1927, at Stuttgart’s famous Weissenhof exhibition of show homes designed by the cream of the avant-garde – Mies van der Rohe, Walter Gropius, Peter Behrens, Le Corbusier, Josef Frank and many others – over half the architects chose to adorn their projects with Thonet furniture.

But a revolutionary new furniture typology, exemplifying modernism’s embrace of new materials and its radical conceptions of space, was also exhibited at Stuttgart. The cantilevered chair in tubular steel has been the subject of books, exhibitions and even an entire museum in Lauenförde, in part due to its contentious authorage. It is generally, legally, but not universally agreed that Mart Stam conceived of the principle, believing that it could result in an affordable chair for the masses, constructed from scrap metal and clamps.

In 1926, he communicated this idea to Marcel Breuer, who had already furnished the Dessau Bauhaus in bent metal, and to Mies. Both promptly created their own versions, introducing springiness and elegance to the concept. The legal repercussions were tortuous and ridiculous, but the initial ruling of 1932 decreed that Breuer’s designs in particular were ‘imitative’ of Stam’s concept and thus under the latter’s ‘artistic copyright’.

The connections between tubular steel furniture and Thonet’s bentwood heritage, both symbolic and practical, were manifold – lightweight, transparent structures, capable of mass production, with simple forms derived directly from experimental materials and manufacture. The firm began buying tubular steel designs in 1928, and, after abortive efforts by Breuer to manufacture his own designs, was soon manufacturing both his and Mies’s cantilevered chairs, alongside such novelties as the famous LC4 chaise longue by Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret and Charlotte Perriand.

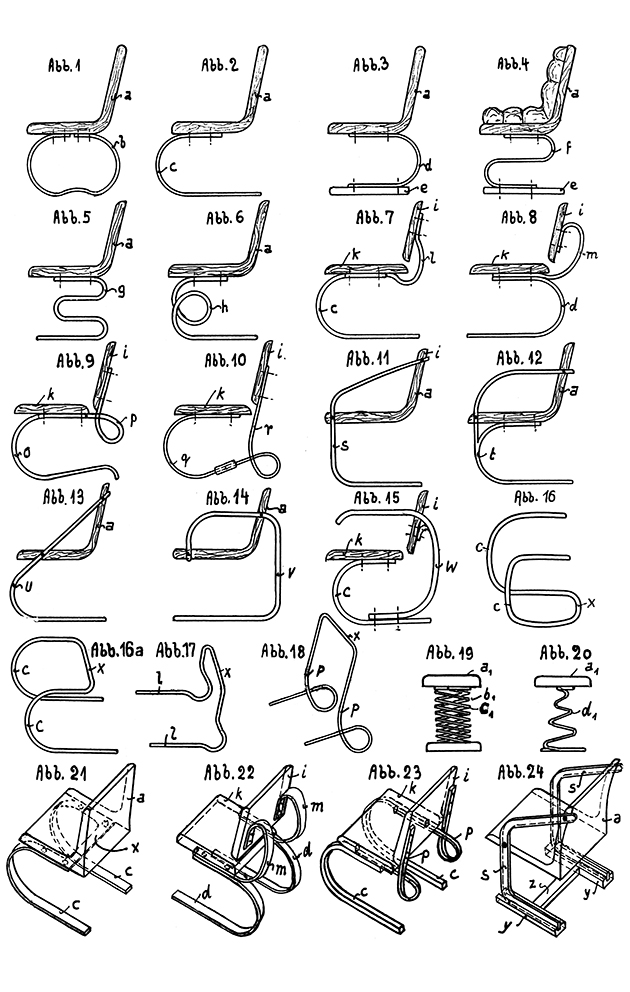

The S33 on the front of the 1930-31 catalogue and 1929 patent drawings by Stam

The S33 on the front of the 1930-31 catalogue and 1929 patent drawings by Stam

The modernist community was drawn to Thonet’s prestige, its factories, its distribution, its commitment to quality, its pioneering history and, of course, the financial muscle that allowed it to invest heavily in the mass production of tubular steel furniture. Thonet became synonymous with modernist design, producing everything from tea carts to hi-fi stands, sending out a new generation of crates, each now holding 100 of Breuer’s B5 chairs.

In ten years, it was all gone. During the 1930s, designers across Europe and America tried their hand at tubular steel, while mass-market firms churned out imitations, repositioning the genre as a cheap option for schools and factories. Political hostility led to the closure of the Bauhaus in 1933 and the emigration of much of its faculty. Thonet moved upmarket, focusing on opulent, hand-worked and customisable chrome models, marketed with the imprint of its famed designers.  Sebastian Herkner’s 118 chair – the wicker cane seat is a reference to the classic No 14

Sebastian Herkner’s 118 chair – the wicker cane seat is a reference to the classic No 14

Sales and profits were maintained, but a wider stylistic backlash was gathering pace. British commentators as diverse as Aldous Huxley and JB Priestley condemned the metal infatuation as inhumane, the former stating, ‘To dine off an operating table, to loll in a dentist’s chair – this is not my idea of domestic bliss’. In contrast, Alvar Aalto’s laminated furniture offered an entirely new approach to systematised bentwood, meeting with huge success. Soon, even Breuer was working in plywood with British firm Isokon, before abandoning furniture as a youthful indiscretion.

Such struggles were just a foretaste of the destruction of the Second World War. Thonet’s Vienna sales office and Frankenberg factory were demolished. After the war, materials, investment and equipment remained scarce, while consumer taste was hostile to the severity of mechanised modernity, turning instead to organic form and bold colour. Riven by the dual challenges of copyright and fashion, Thonet retained only two bent-metal chairs in production during the 1950s. And bentwood offered no respite – many of Thonet’s factories were lost behind the Iron Curtain, including vital sites in Moravia with its plentiful beech forests. These were nationalised by the Czechoslovak government to create a new rival, Ton. Bentwood production in West Germany was uneconomic, and was only slowly and partially restarted, gaining speed in the 1970s when a new taste for Victoriana and ‘authenticity’ emerged.

Yet the firm survived – thrived even. Oddly, its greatest success took place in the US – the new capital of modernism. The complexities of global production had left Thonet with outposts in France and the US, which joined forces to become a separate company in 1938. Its fresh brand – ‘bent-ply’ – was introduced under the handle ‘Solid, Sturdy, Strong, Streamlined’. Using new methods in electronically moulded plywood, this rather heavy-handed reinterpretation of Aalto was affordable, indestructible and hugely successful. Some made it to Germany, including systems by Raymond Loewy progeny Joe Adkinson.

Bentwood furniture is still produced in the company’s factory in Frankenberg, Hesse

Bentwood furniture is still produced in the company’s factory in Frankenberg, Hesse

By the mid-1950s, more than 100 models were in production, gaining anodised aluminium equivalents. A sprinkling of big-name designers were brought on board, including Ilmari Tapiovaara, Walter Gropius and Abel Sorenson, whose rather gawky offering furnished the UN General Assembly Hall in New York. The French firm, which gained its independence in 1962, offered more expressive bent-ply options, while also championing the young Pierre Paulin.

In Germany, Thonet remained a family firm, surviving the post-war years by producing simple slatted chairs for shops, restaurants and even the new Bundestag in Bonn. The consumerist boom of the 1950s ‘economic miracle’ allowed a more expansive approach, drawing on the Eameses and Arne Jacobsen, often using thin tubular steel frames and moulded plywood seats. The most striking remains Eddie Harliss’s ST664 of 1954, which, despite its beautiful, cone-like form, had a brief, unsuccessful production run, as did Rudolf Bernd Glatzel’s gorgeous lounge chair in teak.

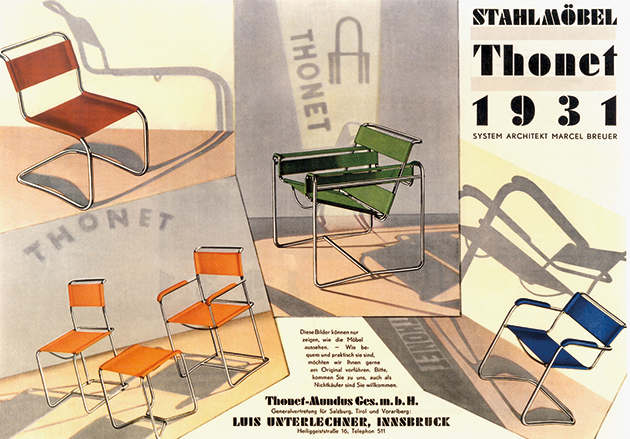

1931 catalogue showing the cantilevered S33, credited to Marcel Breuer

1931 catalogue showing the cantilevered S33, credited to Marcel Breuer

More traditionally corporate offerings met with greater success, such as design head Günter Eberle’s simple ST701 in curved plywood or Harliss’s pared-back ST860. The latter remained in production for a couple of decades, its square-steel structure indicative of Thonet’s partial engagement with the ‘gute form’ of the Ulm School. Throughout, the heritage of tubular metal and bentwood remained in play, including such beautiful homages as Hannah von Gustedt’s ST412.

The resolution of copyright battles around the cantilevered chair in 1961 allowed the reintroduction of iconic models from the 1920s and 30s, especially as the opulent modernism of the American office began to infiltrate Europe. This financial boost coincided with a more vigorous engagement with the contemporary design scene, exemplified by a series of commissions from Verner Panton that remain surprisingly little known today, including entire seating systems and rotating models with adjustable sausage backrests. Most innovative were Thonet’s two plywood versions of Panton’s S-chair, which beat Vitra and Herman Miller’s fibreglass classic to market by a year. Finished to mimic the appearance of plastic, they met with a predictable scorn for their failure to adhere to mantras around truth to materials.

Breuer’s S64 and S32, with their distinctive Vienna wickerwork

Breuer’s S64 and S32, with their distinctive Vienna wickerwork

Thonet’s new design eclecticism was high risk – none of Panton’s designs stayed in production for long – but a belated engagement with plastics did result in one of its greatest post-war successes. The Flex system by Gerhard Lange went into production in 1974, mixing polypropylene seats and solid beech legs. With its echoes of contemporary Italian design, it soon comprised the majority of both Thonet’s production and sales. But it was an exception – despite a few bold gestures towards postmodernism and pop in the 1980s, courtesy of the likes of Ulrich Böhme, Christiane von Savigny and, with particular gusto, Rainer Fuss and Maika Matuschik, the contract and office markets proved resistant to frivolity. It became apparent that adherence to quality and a brand aesthetic were essential. Thonet turned to long-standing areas of expertise and manufacturing strength, avoiding quality issues around outsourcing, whether plywood or plastic, and commissioning designs that reacted to its library of classics, exploring, and occasionally combining, their forms and materials.

This is a course that, by and large, has been steered ever since, and it is a surprisingly difficult one. New, affordable products are still required that respond to customer expectations around evolutions in both functionality and aesthetics, without eroding their understanding of and attachment to the Thonet brand. New pieces produced in the 1990s generally failed to achieve this balance, leading to a period of relative stagnation. Those that pursued new technologies or divergent aesthetics, however well received by critics, tended to struggle – for instance, the impressive K191 by Danish maestro Eric Magnussen or the S240 by Wulf Schneider. Neomodernist offerings from Delphin Design and Norman Foster proved more reliable.

designed by Michael Thonet in the 1850’s the Loopback has smooth lines and signature curves makes it a staple

designed by Michael Thonet in the 1850’s the Loopback has smooth lines and signature curves makes it a staple

Similarly, recent attempts to dip a toe in the quagmire of the domestic market have met with mixed results. Without the necessary depth of marketing budget or compromises around the durability of aesthetic and product, this direction is too challenging for a mid-sized family firm. Yet the list of designers who have contributed over the last decade remains impressive – Pierro Lissoni, Alfredo Häberli, James Irvine and Konstantin Grcic, among others. The latter two were brought in for a collaboration with Muji, providing astute re-imaginings of the No 14 bentwood chair and of Stam’s cantilever designs. Innovation is prized, and the temptation to retreat into profitable mining of Thonet’s modernist classics – still a substantial revenue stream – has been resisted.

Yet it is noticeable that, rather than more flamboyant designs, it is the careful, controlled precision of designers such as Naoto Fukasawa that has met with greatest success. The latest in this tradition, Sebastian Herkner’s 118, was commissioned by Thonet’s new art director, Nobert Ruf, appointed last year to ensure clarity around the brand’s design and market focus. Herkner’s simple, affordable elegance has been warmly received by all sectors, aided by its nods to the firm’s bentwood heritage.

For all its conflict and contradictions, the Bauhaus laid the foundation of modern industrial design. The belief that harnessing new forms and materials to the engines of mass production could bring about a new, egalitarian society proved optimistic – the manufacture of Bauhaus designs remained a craft activity and its social aspirations withered. Despite talking a good game, little has changed in the high design that today dominates fairs and galleries.

S5001 sofa by James Irvine (2006) BELOW LEFT S33s in various finishes

S5001 sofa by James Irvine (2006) BELOW LEFT S33s in various finishes

Bereft of the Bauhaus’s utopian ideals, all that remains are inventive indulgences to satisfy collectors and marketing requirements. Design that aspires to a more pragmatic integrity, manufacturing products that meet the needs of specific users at appropriate price points, with longevity of structure, surface and aesthetic – otherwise known as industrial design – may seem less seductive, but deserves greater respect.

Thonet produced two of the greatest chairs of the modern era. Such moments may not come again, but the firm has survived the whirlwind of its storied past with a strong understanding of what design, beneath the hype, really is.