|

|

||

|

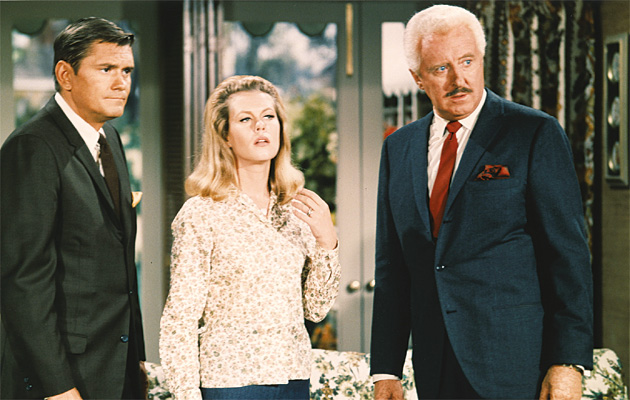

To mark the launch of a new design magazine, Dirty Furniture, which takes the couch as its inaugural theme, Sam Jacob looks at the role of sofa in sitcom This article was first published in Icon’s July 2014 issue. Buy old issues or subscribe to the magazine for more like this Sitcoms take place almost exclusively in one or two interior settings. Their characters seem unable to leave this claustrophobic enclosure. There are two reasons for this Beckettian purgatory. The simplification of location narrows the focus of the show and so helps the audience understand the sitcom’s subject matter: if the show occurs in domestic spaces, it may be about family, marriage or the trials and tribulations of flat-sharing. A work-based sitcom might explore other kinds of social roles and interactions between character types that the scenario gives rise to. The second reason is practical: studio sets have many economic and logistical benefits. The living rooms, office spaces and bars of sitcom-land may look like the living rooms, office spaces and bars of the real world but they are patently not. Sitcoms don’t happen between four walls but within three. They present themselves with a front. The audience looks into the sitcom world as though at a stage, or into a diorama. Rooms are arranged according to theatrical logic rather than real-world principles. Perhaps it’s the sitcom sofa that embodies this more than anything. The sofa is often the landscape against which episodes are played out. It forms a visual and spatial pivot for the room, not pushed against a wall (as our sofas are at home), but set in an open plan. The sitcom sofa – and the cast who sit upon it – tends to face us, the audience. It casts the viewer in the role of the television set: as we sit in our own homes on our own sofas, we find ourselves looking back at some strange kind of reflection. Bewitched A show about the difficulties of a newly married couple, whose expected matrimonial hiccups are compounded by the fact that the wife, Samantha Stevens, also happens to be a witch who can conjure things out of mid-air. At a time when success was measured by one’s ability to consume, Mrs Stevens’ powers were a particularly useful attribute. In the first few episodes she miraculously stocks the new family home with all the accoutrements of modern life, conjuring her sofa with the declaration that it should be “comfortable, something over-stuffed”. Over the course of the show’s run, the Stevens’ lounge room housed a range of sofas, from mid-century Scandinavian modern to a slightly plumper, green and yellow floral skirted number, marking the decade’s transition in fashion.

The Cosby Show Initially designed as a vehicle to launch stand-up comedian Bill Cosby’s television career, The Cosby Show centres on the family home of the Huxtables, an upwardly mobile African-American middle-class family living in a Brooklyn brownstone. Though The Cosby Show set is quite extensive, spanning kitchen, bedrooms and ancillary spaces, the narrative always seems to pan back to the sofa, where problems are first identified and eventually resolved. When Mrs Huxtable tries to replace the family furniture in season five, her husband makes his strength of feeling about his couch absolutely clear, addressing both her and the upholstery: “Thank goodness that my patient cancelled, otherwise I would not have been here to see my wife stab me in the sofa.”

Friends Spearheaded by Rachel Green’s decision to flee the altar, Friends tells the story of six single American 20-somethings in Manhattan. Different living-room sets were employed in this American super-sitcom. The stalwart orange mohair of the Central Perk cafe was strange in sitcom history for being a sofa outside of the home. With super-sized teacups, the sofa completed a decor of exaggerated domesticity and was arranged facing front of the set. The comparison this raises between domestic and public space is important, with the cafe taking on the role of the traditional lounge room, a space to which a disparate group of friends can return in order to find community, something now impossible in the pseudo-private spaces of shared homes.

The Royle Family Low-income British family life at the turn of the millennium. Often over-occupied, The Royle Family’s three-piece suite points, naturally, towards a television. The critic Mark Lawson has described the lack of event: “Beached on their sofa in front of their god of a box, they patiently but hopelessly wait for a revelation that will never come.” The show is far from banal, however, as the circular dialogue and bickering, and confrontation, accumulate into a tragicomedy of the modern multigenerational household. Though often bleak, The Royle Family depicts the equation of family-plus-sofa-plus-television as one of active consumption that leads to dialogue rather than a dead-eyed stare.

Modern Family The sitcom is the story of three connected families in suburban Los Angeles, at the head of which is bumbling patriarch Jay Pritchett. The nuclear family unit is reconfigured by the consequences of divorce, remarriage, inter-racial, inter-generational and homosexual couplings and adoption. The camera roves between different domestic units in mockumentary style. Each set of characters, often perched tightly together on their individual sofas, answer pertinent questions posed by an unseen interviewer whom they address as if s/he is standing directly behind the camera that faces them square on. Caught between being eager to defame others and to please the “production team”, Modern Family reveals the sofa space to be a complex dichotomy of private fear and public bravado. For more information, visit dirty-furniture.com |

Words Sam Jacob

Images: |

|

|

||