|

|

||

|

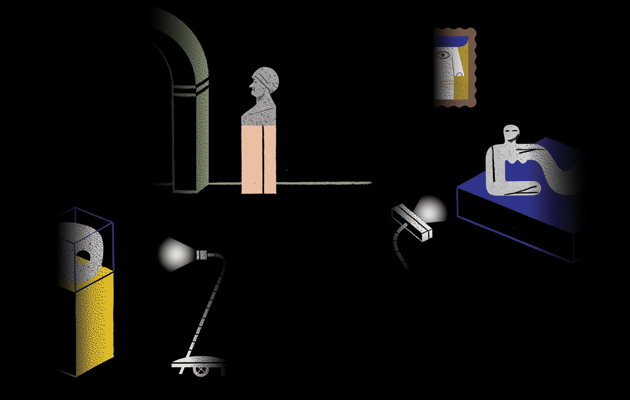

After closing time at Tate Britain, four silent robots move around the galleries. As their flashlights illuminate the walls, an internet audience enjoys a robot’s-eye view of 500 years of Old Masters. But this project is not about art – it is about the special power of a museum at night, and the transgressive thrill of being allowed to enter Much of Umberto Eco’s 1988 novel Foucault’s Pendulum is told by a man hiding at night in Paris’s Musée des Arts et Métiers, a museum of technology. Pursued by mysterious cabalists, the narrator evades the museum’s guards at closing time by wedging himself into one of the exhibits, a periscope. When he emerges in the dead of night, he finds the museum is transformed into a deeply threatening place, a reflection of his own delirious paranoia. The obsolete machines that surround him take on monstrous characteristics, animated by the enfolding gloom; they resemble terrible, vengeful insects or torture devices, “a cemetery of mechanical corpses that look as if they might all start working again at any moment … All ready, these instruments awaited a sign, everything in full view, the Plan was public, but nobody could have guessed it, the creaking mechanical maws would sing their hymn of conquest, great orgy of mouths, all teeth that locked and meshed exactly, singing in tick-tock spasms.” Now Tate Britain has fallen to the machines. Since August, one of its galleries has been nocturnally visited by four silent robots, which glide from room to darkened room examining the paintings by flashlight. And controlling these intruders are … well, you and me, in theory. Members of the public take command via their home computers, giving a global audience a privileged, after-hours, burglar’s-eye view of the museum’s collection. All you need is an internet connection and you’re able to see a side of the museum usually left to no one but security guards.

After Dark, as the project is called, is designed by The Workers, a small east London design studio. It came about as the result of the IK Prize, a new initiative run by the Tate that awards up to £60,000 to a digital project that “enhances public enjoyment” of the museum’s collections. And enjoyment is clearly built into every nut and bolt of the trundling night watch – After Dark has an immediate, obvious charm. The inner eight-year-old sits up and immediately wants its go on the controls, to explore the rooms and watch Old Masters appear in the robot’s lights. “It’s a really special experience walking around a gallery at night,” says Ross Cairns, who founded The Workers with college friend Tommaso Lanza. “It’s a childhood dream for most people. We heard about this prize and saw a chance to do what we’d talked about before: to create robots you can control from the internet, and move around the gallery with a spotlight.” Cairns and Lanza met at the Royal College of Art in London five years ago. Both are graduates of the RCA’s influential Design Interactions course, presided over by Tony Dunne and Fiona Raby, and they had come from quite different design backgrounds: Cairns working in Glasgow in graphic design and advertising, Lanza in Milan as a furniture and product designer. But they have found themselves working together in digital design, in particular making interactive systems for museums and galleries, including the Natural History Museum in Berlin and the Sainsbury Centre. “Neither of us is from a programming background,” says Cairns. “We were just insanely interested in programming, and love to make the tools that we’re using.”

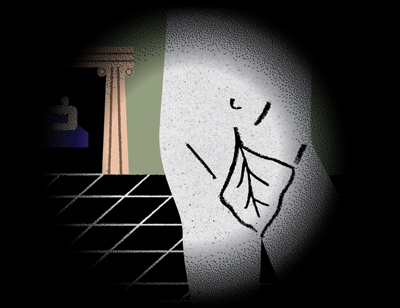

The Workers is based in a small upstairs room in Sunbury Workshops, a Victorian alley in Shoreditch that’s home to numerous young design and tech firms. Icon visited Cairns and Lanza there on a blazing summer day as their robots took shape. They – the robots, not Cairns and Lanza – are straightforward, yet characterful, creatures. Each consists of a basic black domed unit close to the ground, containing the wheels, controllers and batteries. From this rises a long, slender, raking “neck” of brass-coloured tubing, supporting a rectangular black “head” containing twin spotlights and a camera. As you’d expect from something that’s going to be in nocturnal contact with priceless works of art, basic safety measures are writ deep into the design. The robot’s actions are fairly limited – it can roll forwards and turn on the spot, and the head can tilt up and down. Bumpers are set into the edge of the base unit – simple switches that cut the robot’s power if it comes into contact with something. “If you extrude an imaginary cylinder from the base, nothing protrudes,” says Lanza. “The first thing to touch anything is the lowest part of the robot, which would cut the power. There is no chance of anything up high touching anything.” Most of the internal components are off the shelf. Robots have explored the surface of Mars and the deep ocean trenches, so the climate-controlled parquet floors of a museum did not present any outlandish technical difficulties. The most complicated part of the build was the most important for a satisfying user experience: getting the video feed to stream without a lag, a problem they believe they have cracked using a new system called WebRTC.

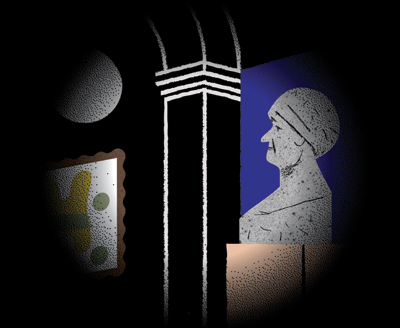

The technology isn’t the really exciting part of the project. Neither is the art, not really. If you want to look at paintings on your computer, use Google Images. “Everyone says ‘what a neat way of visiting the museum’, but obviously it’s better to be there to see the paintings,” Lanza says. “[This is] probably the most inefficient way of enjoying art. It is about art, because art is around it, but it’s a lot more about the space itself. A place like Tate Britain feels very sacred – it’s not the usual gallery, the place itself is a piece. … [it’s] imposing. It feels … it’s as if you’re breaking the space.” As Lanza says, the museum is a powerful space, and that power only intensifies at closing time. Maybe it’s the museum’s status as the guardian of our most important cultural artefacts; maybe it’s the potent ambivalence of a space that is extremely public, but subject to strict rules and restraints – full of velvet ropes and watchful custodians. Any space so hemmed in by taboos invites thrilling transgressions. This can be plain old material gain – the museum at night being the setting for dozens of heist movies. But there’s more to enjoy there than just theft. André Breton, the founder of surrealism, fantasised about the museum after dark as a place where art could be experienced with more privacy and intimacy than during the day, without the same limitations.

In his novel Nadja (1928), he wrote: “How much I admire those men who desire to be shut up at night in a museum in order to examine at their own discretion, at an illicit time, some portrait of a woman they illuminate by a dark lantern.” The somewhat creepy, possessive, sexual undertone of this examination isn’t hard to make out – a dark lantern indeed. But the exhibits enjoy their own freedoms after hours. There is a recurring cultural motif that the museum belongs to its collection after closing time – outnumbered, pinned to the walls and watched closely during the day, the artworks and artefacts literally come to life at night, repossessing the space. This can, of course, be turned to whimsy, as in Night at the Museum, Milan Trenc’s 1993 children’s book, turned into a Hollywood family film in 2006. Or it can be the deeply disturbing idea that Umberto Eco exploits to torment his narrator in Foucault’s Pendulum. After Dark promises an atmospheric experience somewhere between whimsy and fright – Cairns and Lanza say that there is a delicious frisson when your robot encounters another robot making its way through the gallery, first as a light up ahead, then as an approaching machine, a wordless encounter with another “visitor”. Just as the IK Prize intended, this is a new way to enjoy the collection. “It’s cheesy to say, but it lets you see the paintings in a different light,” says Cairns. “You’re in this room full of paintings of people hundreds of years old, and there you have someone’s view into the world. [And] at that moment they’re being confronted by this fairly odd robot, but this robot is also someone’s view into the world. These two things meet eye to eye – neither really sees but you see.”

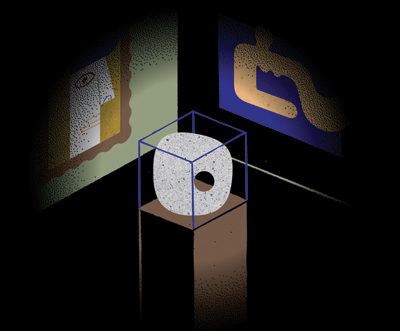

The 21st-century view of the world will increasingly be through the eyes of robots like these. Telepresence – using robots to represent yourself when you can’t be somewhere in person – is already fairly established in business and industry, and has been used in museum settings before. “We’re not doing anything new, we’re just strapping things together,” Cairns says. “There are companies making robots you can put your iPad on and go into meetings. What we’re really interested in is taking these robots into places where they are not supposed to be.” The innovation is imaginative, social – opening up new spaces and methods for interaction. Designers are, Cairns says, “on a cusp”, where they have at their disposal powerful new electronic, digital tools and have not yet truly begun to explore what can be done with them: “off-the-shelf components which are in a way freeing us from reinventing the wheel, or actually the motor controller,” says Lanza. The After Dark robots are composed of these parts: Arduino servos, governed by a Raspberry Pi CPU, and so on. What this means is that designers have the ability to make huge strides in robotics, remote control, video, augmented reality and – most powerfully of all – combinations of these fields.

“You’re riding a wave that’s always at breaking point,” says Lanza. “It’s very fragile ground but very fertile at the same time. Prototype Lego blocks that might fit, might not fit, maybe you have to” – he smacks his hands together – “a bit harder than normal.” The Lego comparison feels apt. There’s a spirit of adventure underlying After Dark, an inquisitive, childlike lack of patience for traditional boundaries. The same spirit animated Out of Bounds, a similar recent project by the digital designer Chris O’Shea, which gave users an “X-ray torch” to peer through the walls of the Design Museum into the store-rooms and closed areas beyond. The museum, with its high walls, clear rules, and treasures inside – has become the perfect challenge for this subversive new generation. This article was first published in Icon’s October 2014 issue: Museums, under the headline “The night watch”. Buy back issues or subscribe to the magazine for more like this |

Words Will Wiles

Illustrations Jay Cover |

|

|

||