|

“We are absolutely crap decorators,”admits Mattias Ståhlbom, one half of the interior architect and furniture designer TAF. “We hardly know what curtains are, and definitely don’t have a clue about wallpaper brands,” says Gabriella Gustafson, the other half of the firm, which gets its name from the three middle letters of her surname. Gustafson and Ståhlbom plunder the everyday for inspiration. They are not afraid of the banal. They even admit to being a bit boring, and therein lies their ingenuity. They make sculptural stairs out of wooden kitchen worktops; they make the ubiquitous trestle new again with the addition of lacquered metal joints and new functions; they add a hand-carved peg to an otherwise perfect machine-made table. But above all they make do. When you enter TAF’s office in the south of Stockholm, their remark about being crap at decorating makes sense. It’s not very cosy. “Sorry about the mess, but we redecorated a while back and haven’t really organised it yet,” says Gustafson, as we return from a day at the Stockholm Furniture Fair where TAF designed the display concept for the graduate exhibition Greenhouse. Lights are flicked on, the kettle is set to boil and the iPod starts hopping from Dolly Parton to Joy Division. The mess mainly consists of prototypes, skillfully made miniature models of their furniture designs and stacks of research material. But it’s not this that makes it uncosy, it’s the bareness: panoramic windows look out over a bleak Stockholm in February twilight, and the newly painted white walls are in stark contrast to the general disorder. This starkness, however, is fitting as their aesthetic is built on necessity. “We graduated during the last recession and it was very hard to get any work, so we started doing projects for friends on really low budgets,” says Ståhlbom. “We had to source cheap materials from builder’s merchants and made a virtue of the basic nature of the materials. This approach has developed into our method, even if we haven’t got the same economic restrictions any more.” This method of making do seems to hit a nerve in the current economic climate, but TAF, a favourite on the Swedish design scene, hasn’t felt the effects of this recession yet. “We don’t give a damn about the economic crisis,” says Gustafson. “We only have one employee anyway, so it’s not like we have to fire half of our staff.” Ståhlbom butts in. “We have never had as much work as we have now in any case.” There is nothing showy about TAF, as people or as designers. They are softly spoken, pensive and almost entirely dressed in black. “Our products don’t exude exclusivity, in fact they are a bit basic,” says Gustafson. There is something charming and old fashioned about them, even the way they speak, frequently using old Swedish sayings that translate into entertaining English. They explain how they “make soup from a nail”, “dig where they stand” and how they “conjure with their knees”. Put simply, they use what surrounds them. TAF is design’s personification of French philsopher Michael De Certeau’s seminal work The Practice of Everyday Life, in which he observes that the everyday works by a process of recombining existing rules and conditions to create new outcomes. In that vein TAF makes a room divider that is inspired by a roadworks barrier, or picks the colour for a product from the yellow coating of a pencil. “Our design is based on recognition, and because of that people feel a safeness and a certain nostalgia in our products,” says Gustafson. The pair met while studying interior architecture and furniture design at Konstfack in Stockholm. They graduated in 2002 and set up their office the same year, but it has taken them until now to start getting noticed internationally. Last year, Japanese brand Cïbone put TAF’s Trestle into production. Originally an idea developed for a Danish exhibition of furniture for the elderly, it is a simple system for tables, beds and shelving based on the traditional trestle, reinforced with metal. “Like a support stocking basically,” says Gustafson, “so that it lasts longer and can follow you through life.” When we meet they are in the middle of discussions about Milan, a furniture fair that TAF has yet to make its mark on. “We have been thinking about Milan a lot, but there is so much going on that we would just drown in the sheer quantity of events if we don’t do the right thing,” says Ståhlbom. Luckily, the right solution came knocking on their door in the shape of the prestigious Spazio Rosanna Orlandi gallery in Milan. TAF is one of a handful of designers showing in the gallery during the fair, alongside Jaime Hayon and Naoto Fukasawa. For TAF it’s about finding the right context for an idea and this is one the designers have been toying with for some time, as the prototypes in the studio show. Soft Parcel applies the same technique used for wrapping gifts to upholstering furniture. In Soft Parcel, brown fabric is wrapped around blocks of foam stacked on top of each other like parcels in a sorting office. They can be stacked up to make sofas, chairs and cushions.

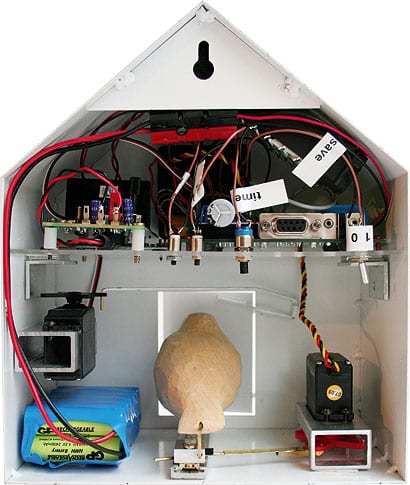

Soft Parcel, 2009 Maybe TAF’s style is best described as a humane asceticism. Despite the occasional extreme minimalism, there is always a sign of the handmade and cared-for, even in the most machine-made of products. For example, their outdoor furniture collection, IOU, with its fine, likable proportions, could easily be overlooked as a standard design from some anonymous manufacturer, but it is not until one studies it closer that you see the real beauty. The wooden slats that make up the seats, backrest and table have different thicknesses, breaking up an otherwise monotonous surface. And holding the table top in place is a peg that is hand carved and then painted a striking colour. This last touch is courtesy of a Russian prisoner who helped make the table as part of Criminals Return Into Society (CRIS), an organisation that TAF has collaborated with on a few projects. The cuckoo clock on the table in front of us also started as part of the CRIS initiative. “It recently arrived from the cuckoo-clock factory in China,” says Ståhlbom, unaware of the incongruity of what he has just said. It is a house, produced in powder-coated metal, but the cuckoo itself is a puffed-up character in a minimalist surroundings. “The idea is that it should be life-size, like a sparrow or thereabouts,” says Gustafson. The hand-carved finish looks like a failed attempt in a primary school woodwork class, and it’s this contradiction that makes the clock appealing, even funny. Just like Ståhlbom and Gustafson themselves. Despite their self-proclaimed shortcomings as decorators the partners have managed a fair number of interior architecture projects, most recently a gym in the centre of Stockholm and a doctor’s surgery for private healthcare group Carema south of the Swedish capital. “Here’s the inspiration bag,” says Ståhlbom, holding up a plastic bag full of sticking plasters and gauze instead of fabrics and colour samples. The surgery’s reception has been crafted out of a patchwork of different white and beige materials, copying the tones of the mess in the plastic bag, but the overall effect is one of simplicity. The most striking aspect of TAF’s work is its simplicity, the minimal mark they leave on their projects, leaving it up to the end user to make it their own. In that sense they are embracing a long tradition of Swedish 20th-century design, refreshingly free from ego. At the same time their blandness can be seen as symptomatic of a design scene that is currently at a crossroads.A new generation of Swedish designers is abandoning the country’s tradition of minimalism for a more diverse aesthetic, but unfortunately few local manufacturers are as courageous. “They need to be more daring,” says Ståhlbom. The same day we meet, Svensk Form (the Swedish Society of Crafts and Design) abandoned its premises and moved in with the architecture museum, obliterating the only state-funded exhibition space for contemporary design in the capital. It’s a peculiar move at a time when Swedish design urgently needs direction. TAF agrees. “For us it’s the analysis that’s the most important and that is often the downside to our work as designers,” says Gustafson. “We are rarely given the space to debate and talk about our ideas and concepts and then design risks becoming very boring.”

Desk lamp from the RH Chairs project, 2009

IOU garden table for IOU, 2007-8

Foto lamp for Zero, 2006

Basel cuckoo clock, 2006. Now in production with Design House Stockholm

Basel cuckoo clock, 2006. Now in production with Design House Stockholm

Stairs made from pine kitchen worktops, 2006 (image: Bobo Olsson)

Reception desk at the Carema surgery, Stockholm, 2008 (image: Ake E:Son Lindman) |

Portrait Marcus Palmqvist

Words Johanna Agerman |

|

|

||

|

Waiting room at the Carema surgery, Stockholm, 2008 (image: Ake E:Son Lindman) |

||