|

|

||

|

Rolf Sachs is as intriguing and multifaceted as his work – or, rather, Sachs’ work reflects the many facets of the man himself. Descended from a well-known German industrial family, he has been working in “the field where art and design overlap” for more than three decades, also donning the mantles of investor, collector and businessman. His multidisciplinary studio produces everything from furniture and lights to photography, stage sets and installations. “Every show we do normally has a few functional pieces and a few sculptural pieces, but even the sculptural pieces will always be done out of the functional,” Sachs says His approach is also decidedly conceptual. “We don’t do design – form-giving in itself,” he explains. Rather, the work is driven by ideas, using elements in a different context or adding an essence of humour or, as he puts it, “a twinkle in the eye”.

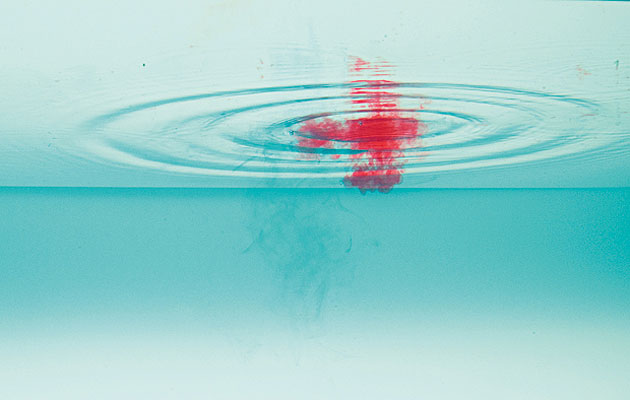

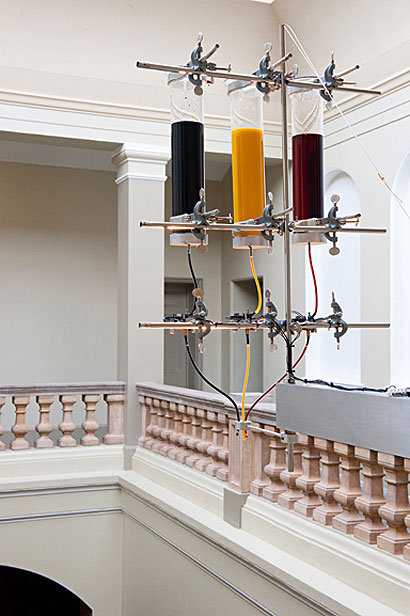

Sachs has had a busy summer, with his exhibition Herzschuss – “shot to the heart” –running until the beginning of September in Switzerland, and many other projects in the pipeline. For Herzschuss, Sachs drew inspiration from the Swiss Engadine region, where he grew up, embracing the craftsmanship of the area. In September, the studio launched a collaborative collection of pieces with bespoke furniture designer David Linley and The Journey of a Drop, an installation in the V&A’s Henry Cole staircase. The installation makes use of the soaring atrium, with individual drops of coloured ink released from a 35m height into a tank, swirling and mixing before gradually dissolving. An immediately captivating piece, it is also deceptively complex. In true Sachs fashion, it uses finely-tuned machinery, specially developed liquids and pigments and underwater microphones to amplify the sound of the falling drops. As with much of Sachs’ work, it is the result of constant experimentation and the pursuit of new ideas. “I want to find new things – it’s always about the invention. That’s why I often say that we’re a creative lab,” he says.

As well as inventing the new, Sachs likes to reinvent the classic. For example, his beloved Koln chair – a sturdy, functional chair originally produced by Horgenglarus in Switzerland – crops up in many different guises, cast in wax, spliced into a Siamese twin version in the Koln-Doppelstuhl or furnished with a cheeky spyhole. The last two of these were shown at this year’s PAD London in October by Gabrielle Ammann gallery, alongside the sculptural No News table, which builds on Sachs’ experiments with casting in wax, a process that is surprisingly underused in art, he says. He also showed some as yet unnamed lights with Priveekollektie.

Despite its variety, Sachs believes his work has some distinctive characteristics, such as a deconstructivist attitude, an aversion to the decorative, and an exuberant and often surprising use of materials, including natural materials “with soul”. In his new studio, at the Gas Works in London’s Chelsea, material samples – from wax, felt, aged copper and zinc, to amber resin, sheep’s wool, anthracite coal and honeycomb – crowd the surfaces. There is also a table made from a reclaimed giant “Ausfahrt” (exit) sign from a German motorway, which indicates Sachs’ appreciation of a certain design aesthetic. “I have a very German language in my design,” he explains. “I like edges, I like things we use every day, and I like certain archaic shapes. I have a wonderful time in a hardware store.” And no matter how incongruous that might sound, you can somehow imagine the polymathic Sachs just about anywhere. |

Image Susan Smart

Words Anna Richardson Taylor |

|

|

||