|

While the camera is clicking away Philippe Nigro and Michele de Lucchi are laughing. It’s the kind of relaxed and spontaneous laughter that comes from a long-term friendship. For a moment they seem completely unaware that there are four people watching from behind the camera. Their relationship is one of a dying breed in the design industry – that of apprentice and master. Nigro looks a little tired, but then again the French designer has been working round the clock for years now. On top of his full-time job with Michele De Lucchi, one of the maestri of Italian design, he has pursued a freelance career on evenings and weekends, working for the likes of Ligne Roset, Sintesi and Skitsch. In many ways Nigro is an anomaly. While other designers would scarper at the first whiff of personal success, Nigro has been biding his time for eleven years. Only now is he thinking of leaving his mentor behind. So it’s only natural that he should be suffering some separation anxiety. “If I were to start my own practice,” says the 35-year old solemnly, “I wouldn’t see all these projects, the architecture, the graphics, all the people.” The decade he has spent with De Lucchi has shaped him as a designer. “I’ve discovered a lot working with Michele – all the faces of the design industry: architecture, furniture, interiors.” The world outside the five-storey office on Via Varese in Milan, is a jungle of uncertainty in comparison. We meet in the workshop of Michele De Lucchi’s studio. It’s a state-of-the-art woodwork room with all manner of woodcutting and planing contraptions, like a dad’s garden shed on steroids. This is the birthplace for much of their work together and it has a warm, somewhat sweaty, air of productivity and anticipation. For now the machines are quiet and completely still. It’s at the end of the working day and the eve of the opening of the Milan furniture fair, where both of them are showing a handful of new products – some that they have worked on together, some separately.

These days, the younger designer’s work gets more attention. Which is ironic, because some of Nigro’s most celebrated pieces to date, such as the jigsaw-like Confluences sofa for Ligne Roset and the genius two-in-one Twin chair for VIA, have come about in his spare time. “It’s tiring,” says Nigro. “When you work all the time it is difficult to define this frontier between home and work, it doesn’t exist at the moment.” De Lucchi, however, doesn’t mind his protégé moonlighting. “I’m always asking my collaborators to work for themselves,” says De Lucchi. “But not everyone does. Out of the 42 people we have in the studio there are only three that do things for themselves. This profession is something that you have to be fully dedicated to.” Nigro later reveals that De Lucchi practices as he preaches. Apparently he works all the time, spending his weekends in this workshop, making his wooden models of imaginary houses – they work both as evocative and beautiful sculptures and as sketches for other projects. Michele De Lucchi’s beard and round, horn-rimmed glasses make him look older than his 60 years. He was the last design director for Olivetti before it mutated into a communications company in the early 2000s. He set up Memphis with Ettore Sottsass, Martine Bedin, Aldo Cibic, Matteo Thun and Marco Zanini, and admits: “Memphis was a catastrophe, it wasn’t successful at all. It was very influential, it was distributed all over the world and the Memphis idea was very famous but in terms of commercial success …” De Lucchi puts his thumb and index finger together to form a zero. He set up his own studio in the 1980s and nowadays the architectural projects take up most of its capacity; Nigro is one of only three dedicated product designers on the staff. When they speak, and De Lucchi does most of the talking, they seem completely in tune with one another. At times De Lucchi seems almost fatherly and Nigro listens intently. It was once common for designers to go to Milan to cultivate their trade under the tutelage of an older generation. It was a natural stop on the way for Patricia Urquiola, who apprenticed with both Castiglioni and Magistretti, and for James Irvine who worked with Sottsass. But this is rare nowadays, the idea of it a little dated. A decade fixated on limited-edition design pieces and design-art has made it easier for young designers to find sources of revenue and practise on their own. Nigro then, is subscribing to a slightly old-fashioned way of working, one which isn’t entirely in tune with his contemporaries.

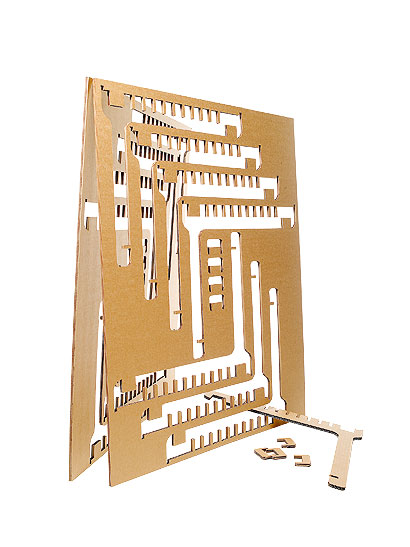

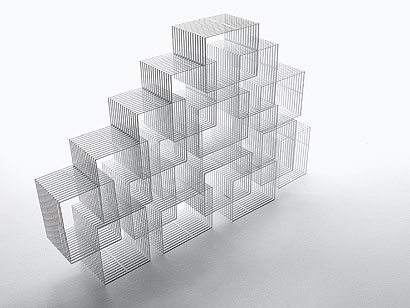

Lancelot cabinet for Decastelli, 2010, Philippe Nigro After eleven years with De Lucchi, where does Nigro’s own identity as a designer begin? “It’s difficult not to be influenced by Michele because he has such a strong personality and style,” says Nigro as we walk through the studio. In stark contrast to De Lucchi, Nigro has a very quiet, almost timid way about him. You get the feeling that Nigro isn’t interested in cultivating a flamboyant personality for the sake of publicity – maybe he finds it difficult to move on because he lacks an instinct for commercial success. “I’m not interested in being a design protagonist,” he says in his slow French drawl. “I’m not interested in being in the spotlight. To produce good design and to be proud of what I do, that’s the most important to me.” Even this late at night the office is full of people busy with installing an exhibition for the Produzione Privata collection in the entrance lobby. It’s a minimal collection, using almost exclusively wood and blown glass, that De Lucchi has been producing with craftsmen since the early 1990s. All of the pieces are simply constructed without screws or fittings to ruin the clean lines. It’s almost Shaker in style. The same pared-down approach to design can be found in Nigro’s work. Many of his pieces seem almost childish in their simplicity, like the Ligne Roset sofa, which is a huddle of foam seats slotted together like a giant jigsaw. Other pieces, like the Cross-Unit shelving, is reminiscent of the steel rods from a Meccano set. Maybe because De Lucchi is so passionate about glass and wood, Nigro seems to avoid these materials in his own work. He favours metal and upholstery and when using wood, he disguises it. The Twin chair has a “skin” of metal that can be lifted off it to create another chair. “It’s difficult, because I bring a lot of myself into the projects with Michele,” says Nigro. “So it’s sometimes difficult to work out my own personality.” But he admits that there is an altogether different pleasure in seeing his own designs in production. “It’s my big satisfaction because I know I did it all on my own.” So what does De Lucchi make of his protégé’s work? “Philippe’s design is too idealistic,” he says as we sit down at his big, wooden desk on the top floor of the building. “He believes in good ideas too much. In my experience I know that good ideas are not necessarily good products, and vice versa. And good products are not necessarily good design. This is part of the paradox of the market.” It might seem like a truism, but in an age where a new generation of designers seem intent on setting up on their own as soon as they have a design in production, it’s a healthy reminder that it’s not always easy to survive. “The market is overwhelming everything, designers are part of the market,” continues De Lucchi. “We are chosen and rejected as products so we have to live inside this system – it is not so bad in some ways. It can be badly interpreted but this is the world, we are not walking on the green grass never touched by anybody.” Diversifying has been De Lucchi’s way of surviving the market and at 60 he is as in demand as 20 years ago, fresh out of Memphis “failure”. The five-storey studio and 42 employees is testament to his success.

Twin chair, VIA, 2010, Philippe Nigro In their master-apprentice relationship it’s obvious that Nigro is keen to absorb all the lessons that De Lucchi can teach him in order to safeguard his own trajectory to success. Now the only problem, says Nigro, is that “Michele lets me be so free that it’s difficult to leave.”

Confluences sofa, Ligne Roset, 2009, Philippe Nigro

Cross Unit bookcase by Nigro for Sintesi, 2008

Bisonte stool by De Lucchi and Nigro for Produzione Privata, 2002

Dehors sofa by De Lucchi and Nigro for Alias, 2008

Fata, Fatina mouthblown lights, Produzione Privata, 2001, Michele De Lucchi

An alcove in De Lucchi’s studio, displaying his imaginary houses, Michele De Lucchi |

Image Mario Ermoli

Words Johanna Agerman |

|

|

||

|

Folding chair, Produzione Privata, 2007, Michele De Lucchi |

||