|

Inflated lips, swollen tongue, huge hands, emaciated body. This grotesquely distorted figure is a strange vision of the perfect client, but this is who Mathiieu Lehanneur is designing for. It’s a model by Canadian neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield showing where the nerve endings are concentrated in the body: the more nerve endings, the larger the body part. The sensitive hands are enormous but the arse is tiny. Looking at the model, Lehanneur says that designers have their priorities wrong: “Why are they all so interested in designing chairs?” The French designer hasn’t designed a lot of chairs – only one, in fact, and that was meant to deter people from sitting too long in a fast food cafe. Instead, his work sounds like a list of props from Woody Allen’s 1973 sci-fi film Sleeper. The Andrea purifier uses living plants to clean toxins out of the air. Local River looks like a coffee table crossed with an aquarium – it’s a way of growing herbs and keeping fresh fish in your living room. Db is a ball that rolls towards harsh sounds and emits white noise to block them out. These products might be the future of design – but they also sound a bit like the sort of stuff you would find in a dubious mail order catalogue. Lehanneur comes across as being a bit too good to be true himself. He has a model’s good looks and is a charismatic salesman for his ideas. It’s difficult not to be drawn in by his passionate conversation and wild gesticulations. This energy comes across in the TED talk the designer gave in Oxford in July last year – an 18-minute burst of enthusiasm about the importance of science to his work. He wasn’t putting on an act for the audience; he’s like that all the time. So what’s behind the convincing patter? What is Lehanneur really trying to sell? We meet in the “designer” cafe at the biannual Maison & Objet fair outside of Paris, but this is not Lehanneur’s usual habitat. “I hate trade shows,” he says. “Hate might be too strong a word, but I don’t need and I don’t want to see too much design and too many products.” So what is he doing here, in this vanity fair? (Karim Rashid has just waltzed into the room with a press cohort following him.) Lehanneur’s presence isn’t entirely voluntary: Philippe Starck has chosen him as one of ten French designers that will shape the next decade and his eccentric products are displayed at a remote corner of exhibition hall 7. When Starck preaches, the French listen, and Lehanneur’s photo has just been taken by Paris Match, the weekly chronicle of the doings of Johnny Hallyday and minor European royalty. ”I know I said OK to this,” says Lehanneur, wearily, “but I really would prefer to be in my office working on my projects.”

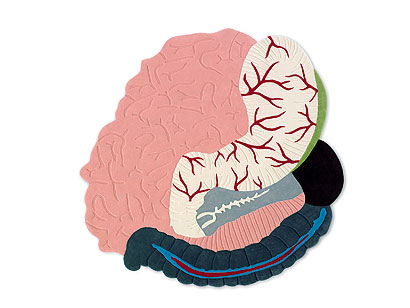

Flat Surgery rug for Carpenters Workshop Gallery, London, 2009 Lehanneur is one of a new generation, identified in Design and the Elastic Mind, a seminal 2008 exhibition at MOMA in New York. This new breed of designer seeks to broaden the definition of design, expanding into fields such as food, medicine and security. In doing so, they are moving into areas traditionally occupied by scientists, and prefer to work with research institutions rather than Italian manufacturers. “I want to feel and understand the human being,” Lehanneur says. “Not as a client or a marketing target, but how it actually works. This is why I work a lot with scientists. They help me understand the human being – what our real needs could be.” So while Lehanneur’s classmates at the École Nationale Supérieure de Création Industrielle in Paris were designing chairs, he was designing medicine. “My project tutor told me, ‘This is not our job. Medicine is for scientists, you can’t do that’,” Lehanneur says. He replied: “I’m sure I can.” At the time, he was funding his studies by acting as a guinea pig in drug trials for pharmaceutical companies, and he saw that taking medicine incorrectly could be as harmful as not taking it at all. So he designed the Objets Thérapeutiques collection, a range of remedies that were easier to use. For example, there was an antibiotic shaped like an endive; each layer represented a different stage of the process, so you start by eating the dark and menacing outer layer and keep going until you reach the core, an unthreatening clear pill. Lehanneur describes his horror at the idea of designing “dead objects”, mere consumer products; by designing medicine he was trying to connect directly with “the living element” – the user. It’s a pity, then, that the Objets Thérapeutiques are themselves now dead: they’re part of the permanent collection at MOMA, not being adopted by the pharmaceuticals industry. Lehanneur is philosophical about this; he sees that it could take years for the corporations to catch up with him, and trying to push these projects now could be demoralising: “I would only become, in French the word is ‘aigre’ [bitter], and I want to keep light.” He seems strangely comfortable with this state of affairs. Perhaps that’s the thick skin that comes with designing things like air purifiers and refrigerator aquariums, which don’t have an established route to market. But it could indicate a troubling lack of commitment to his ideas – he doesn’t really follow through on his sales pitch. A similar pragmatism governs how he runs his studio. His theoretical, mad professor work doesn’t pay the bills, so most of his income comes from commercial projects: packaging and store designs for Cartier and Paco Rabanne and lots of interiors. Right now his studio is working on an interior for St Hillaire church in Melle, in the centre of France, and a workshop for teenagers at Centre Pompidou in Paris, a prestigious commission that is opening this spring.

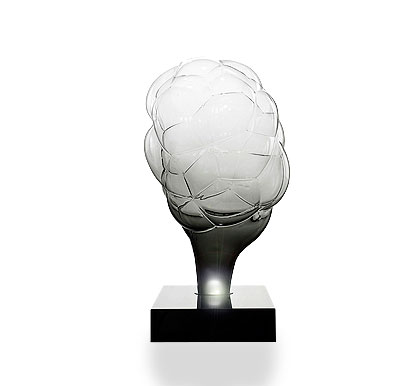

S.M.O.K.E sculpture for Carpenters Workshop Gallery, London, 2009 Even if science doesn’t play any part in these projects, Lehanneur approaches them with the same willingness to explore the human psyche. His most interesting interior to date is the office of David Edwards, a Harvard professor who helped design the Andrea air purifier. It is like an Archigram vision of an office: no tables, no chairs, just a deflated geodesic dome couch, a moss garden for good air quality, a whiteboard and a stack of quilted metal boxes to remind Edwards of the hot dog carts of his native New York. Bizarrely, the space was inspired by a chimpanzee zoo cage, but Lehanneur never shared this detail with his client. “It would have freaked him out,” he explains. Basing an office on a chimpanzee’s cage sounds a bit like the work of architects and fellow Parisians Francois Roche and Philippe Rahm. Similarly, much of Lehanneur’s work involves the immaterial – air, light, sounds – which also concern Roche and Rahm. But Lehanneur denies any links. “The main difference between a guy like Rahm and myself is that I don’t want to work with dematerialisation, I just want to be very effective in using material,” he says. “I could actually produce the physical effect of my products in an invisible way if I wanted to, but in order for the user to be included in the result, you need a visible object. My job is to design the ritual and the relationship between the user and the function.” Many of Lehanneur’s projects, in particular the Andrea air purifier, have a glossy quality reminiscent of 1970s sci-fi films. It turns out that George Lucas’ Star Wars was a boyhood obsession. “The shiny black helmet of Darth Vader was an early aesthetic shock,” says Lehanneur. His Age of the World sculptures for Issey Miyake’s Paris store draw on population statistics for their shape, but if you didn’t know that, these black enamelled ceramics could just be a direct reference to Vader’s helmet. Other than that Lehanneur insists that form doesn’t really preoccupy him much, it is always the last stage of any project, he doesn’t even like to draw and he hates looking at design. “As a designer I do not need to see this lamp,” says Lehanneur while gesturing to Konstantin Grcic’s Mayday lamp on the table in front of us. “Even if as a user I love Grcic’s design, as a designer I don’t want to get this object into my mind because it’s disturbing. Yes, it’s disturbing.”

the Andrea air purifier, in collaboration with Harvard professor David Edwards, Le Laboratoire, 2009

Local River is an aquarium and herbarium for Locavores developed with Anthony van den Bossche for Artists Space, New York, 2008 (image: © Gaetan Robillard) |

Image Ola Rindal

Words Johanna Agerman |

|

|

||

|

Marble altar for church of St Hillaire in Melle, France, due 2010 |

||