|

|

||

|

For over 60 years, this single company has systematised and shaped designers’ notions of colour. So how did that happen? When did Pantone go from dependable but unglamorous tool – a way to accurately match colours – to cultural phenomenon? It might be possible to date this transition quite precisely: to May 2005, in fact, and the International Contemporary Furniture Fair in New York. Ed Barber and Jay Osgerby had been asked to decorate a Pantone-sponsored stand at the fair. Pantone’s most famous product is the exuberant, fan-like colour catalogues that are a staple of designers’ desks. These are filled with square “chips” of colour, which you can hold up next to a sample to tell if you’re looking at Pantone 2029U (a dusty pink) or Pantone 2030U (a dusty pink with slightly more green and black). Barber and Osgerby had some surplus Flight stools, an elegant seat in birch ply they had designed in 1998 for Isokon Plus. They painted a few to resemble Pantone chips in a range of hues, complete with the white band bearing the trademark and the colour’s code. The simple, seductive idea invested a relatively affordable modern classic with additional graphic-design cachet. The Pantone Flights flew off the walls and went into production. The appeal was grounded in Pantone’s ubiquity and dominance in any field of design that reproduces colour – which is to say most of them. It is part of the basic kit. But how did one company end up with this mastery over such a niche, yet fundamental, aspect of design? There have been attempts to catalogue colour, assigning it hierarchies and laws, since Isaac Newton first opened up the spectrum in the second half of the 17th century. Organising colour into a logical system held a particular appeal to modernists: synaesthetic artist Wassily Kandinsky attempted to show that basic colours related to particular forms – sharp, pointy yellow is a triangle, for instance – which would have been a step towards something like a Grand Unified Theory of aesthetics. Certainly Pantone has the reassuring air of a rational, universal, indisputable framework, akin to the Dewey Decimal System or the Periodic Table. But Pantone comes not from Bauhaus modernism or any European Enlightenment project, but from Carlstadt, New Jersey, and the eager world of American capitalism. In 1956, Lawrence Herbert, a graduate in biology and chemistry, went to work for a small printing firm called Pantone. He developed a method to generate the whole range of colours used by the company from a basic stock of just ten pigments (14 today). In 1962, he bought out the company, and in 1963 launched his masterstroke: licensing the formulas to ink manufacturers in exchange for agreements to supply the component colours. In one move, Herbert had almost completely standardised colour manufacturing, with Pantone as the authority. The royalties flowed. The company moved to market itself to specifiers, with those handy catalogues of swatches, refreshed every year, ensuring printers could accurately reproduce designs, and materials from different suppliers matched perfectly. The system was an obvious boon, and caught on. Pantone moved early into digital design, and its most recent strategy has been to tackle the consumer market, helping non-professionals choose and match colours. Its range now includes more than 1,700 shades, including fluorescents and metallics. Barber and Osgerby’s harmless in-joke has propelled Pantone into pop culture. An authoritative yet staid brand has become a way to flash a little design savvy. Pantone mugs, Pantone coasters, Pantone mousemats, assorted other design popcorn – it has perhaps become rather kitsch. |

Words Will Wiles

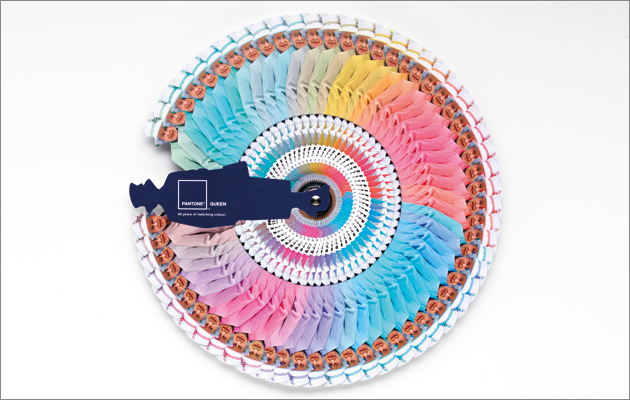

Above: Pantone Queen, created by Leo Burnett in 2012 to celebrate the Diamond Jubilee

Image: Leo Burnett London |

|

|

||