|

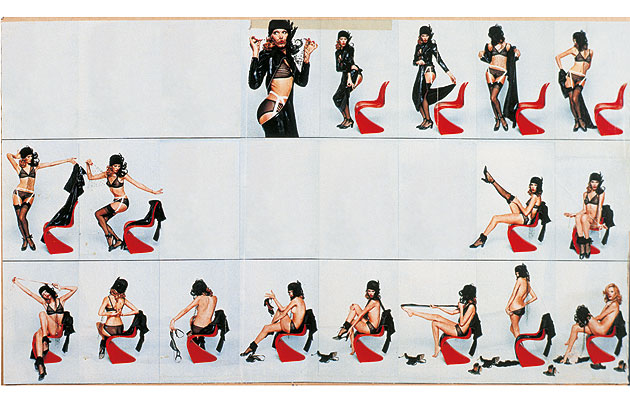

Singer Amanda Lear with a Panton chair in a photoshoot by Brian Duffy for Nova, 1970 (image: Courtesy Vitra Design Museum/ photo: Brian Duffy) |

||

|

There is something slightly disingenuous about Vitra’s announcement that 2010 is the 50th anniversary of the Panton Chair. By the company’s own admission there are no precise details of when Verner Panton conceived his classic design. In 1960 Panton did have a Danish plastics company make a mock-up of a one-piece cantilever chair, but it wasn’t until 1963 that he met the directors of Vitra and it would be another four years before it would hit the market as the company’s first independently manufactured product. To compound matters, Panton’s mock-up is a demonstration of the principle rather than a refined prototype. It could not be sat on and contains none of the sweeping elegance of the final design. But is this historical detail relevant? After all, we’re supposed to be celebrating Panton’s genius in coming up with the first one-piece plastic injection-moulded chair, a milestone in furniture design. The trouble is, it appears Panton was not the first to arrive at the form that would become his most famous work. Two other highly respected Danish furniture designers had produced mock-ups far closer to the final shape of the Panton Chair than Panton’s first attempt: Gunnar Aagard Andersen in 1953 and Poul Kjaerholm in 1955. When the Panton Chair finally appeared in 1967, Aagard Andersen even went as far as to accuse Panton of copying him. This was perhaps unwise considering the broader context. For designers in the 1950s interested in new technology, making a plastic chair was a common goal. As early as 1947 Mies van der Rohe had toyed with the idea and as fibreglass reinforced polyester resin became available, Charles Eames began experiments that led to his famous shell chairs for Herman Miller and Vitra. As Mathias Remmele points out in Verner Panton: The Collected Works, the chair’s form was really dictated by the material and the decision to make it a cantilever that could be fabricated in one piece. To make a plastic chair that did those things, it would have to be made a certain way. So it’s hardly surprising that Panton, Kjaerholm and Andersen’s designs were so similar: there was no other way of doing it. To put it simply, it was an idea whose time had come. But as a professor of mine was fond of saying, “ideas are cheap”. Panton’s great achievement was not the design of a unique chair, but the commitment to seeing it through to mass production, and to ironing out problems thereafter. While Anderson and Kjaerholm’s designs languished in their portfolios, Panton worked tirelessly with Vitra’s developers over two decades, changing the plastic, refining and strengthening the form in response to breakages and eliminating hand finishing to reduce cost. Vitra continued development even after Panton’s death, releasing a polypropylene version in 1999. While the tenacity of its designer and manufacturer made the Panton Chair available, its distinctiveness and timeliness have endeared it to the public. It combines the gravity-defying magic of the cantilever and the ingenious economy of its one-piece construction with the voluptuous grace of its compound curves. (Its sexiness is borne out by the regularity with which photographers have chosen to shoot nudes upon it.) George Nelson called it “a sculpture, but not a chair”; he was critical of its bulk compared to shell chairs with metal legs, and he has a point. But more importantly it served a generation eager to break with tradition and find new expressions in every aspect of culture, furniture design included. It evokes 1960s hedonism and yet retains the ability to look strikingly modern, as Zaha Hadid Architects proved last year when it specified the chair for its JS Bach Chamber Music Hall at the Manchester International Festival. |

Words Tim Parsons |

|

|

||