|

Montreal’s Moment Factory is 12 years old and the interactive multimedia studio is so successful that staff numbers have almost doubled in the past year and it is considering opening offices in LA, New York and Europe. But can a loose culture of multidisciplinary teams incubated in one giant room survive that much growth? A visit to the studio begins by finding a red brick warehouse next to the Canadian Pacific railroad tracks in Montreal’s Mile End. There is a butcher around the corner, but the nearest cafe is blocks away, past Hasidic women pushing prams by empty storefronts and permanent construction sites. Like a lot of Montreal, it isn’t dangerous, just dormant. Moment Factory’s loft, which it has occupied since 2005, is the second floor. The room is very white. There are touches of colour, such as hanging, orange, plastic panels, but it’s mostly a pleasant mess: printed memes, pieces of models and the treasured detritus of celebrity projects. Though the studio specialises in the control of LEDs, the space is lit by daylight and industrial lamps high above, which have been restored by lighting designer and director of scenography, Gabriel Pontbriand. A drum set sits like a wall around one desk and communal skateboards are provided, though tentative riders seem to prefer straight lines. One rolls warily by, stops to blush and turns the board with her hands. The reception desk is also a meeting area and kitchen. They tell me they can’t talk about projects not under contract, but don’t mind meeting about them around me. “I’m a journalist,” I warn. “That’s okay, maybe you’ll give us some ideas.” It’s a matter of age, philosophy and some luck. Moment Factory’s average employee is 30 and the three partners – Dominic Audet, Éric Fournier and Sakchin Bessette – seem rigid only about producing interesting projects. The result is a relatively flat organisation and people who appear to enjoy jobs free from the middle-management bullshit that can mire growing studios. Still, an employee told me anonymously that profitability comes up more and more.

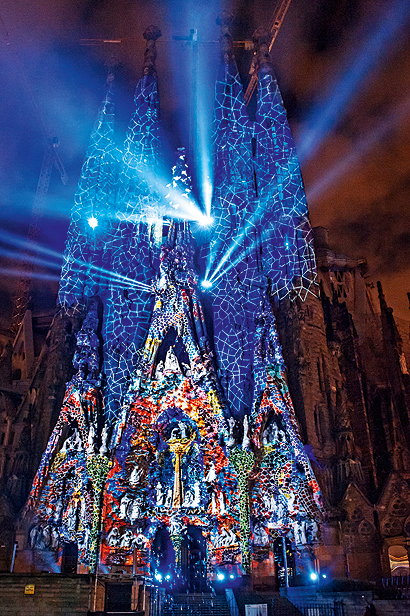

Ode à la Vie at the Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, 2012 (image: Pepe Daude/Basilica Sagradia Familia) Personal ventures – if there’s ever a slow period – and sabbaticals are encouraged. The hours vary with each project and the studio of 120 has no human resources department (“to keep it human”). First-year designers tell their bosses an idea is “fucking boring”. “He was right,” admits Pontbriand about the project for a DJ booth. They didn’t go ahead with it, rather than making something dull. Past reception are the producers, each responsible One of the newer people in the room is a development director, who was hired to deal with the flood of interest that followed the Super Bowl half-time show. Bessette explains that the success of Madonna’s Moment Factory-powered performance became shorthand for the studio. “It can be mysterious what we do, even for our parents. Now we can say, ‘did you see the Super Bowl? That’s the kind of stuff we do’.”

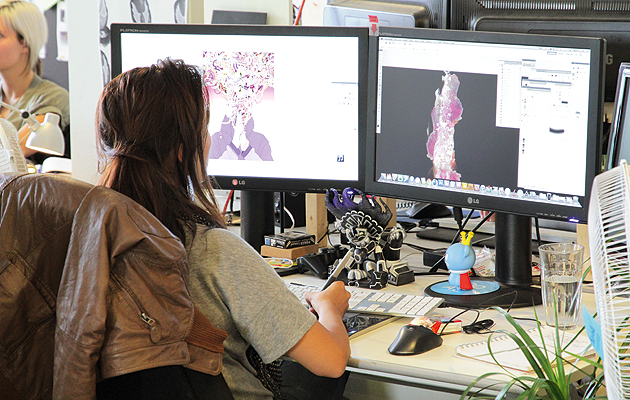

Time Tower, Los Angeles International Airport, 2013 Founded in 2001 by Bessette, fellow VJ Jason Rodi, and Audet, who was then at the Montreal planetarium, the studio took advantage of the revolution in video technology and prospered early through its work with the Montreal-based international circus empire Cirque du Soleil. Moment Factory followed Cirque ley lines southwards to the US market, Vegas, cruise ships and corporate events. The ideas of “l’œuvre commune” and of churning through freelancers and small shops to stay fresh was inherited from the circus, explains Fournier, who was vice president of “all the weird projects” and Moment Factory’s client at Cirque. He joined Moment Factory after Rodi left to make films in 2006. One of the studio’s turning points was Nine Inch Nails’ 2008 Lights in the Sky tour. Moment Factory produced a groundbreaking interactive show with NIN frontman Trent Reznor that used LED lattices in front of the band to create dynamically generated illusions. Creating this “digital architecture” involved working 80-90 hours a week, recalls Pontbriand. “We pushed the boundaries. It was not a party.” The show was controlled by custom software kludged to existing control and lighting devices, which was remarkably effective. The effects were so tight that many assumed it was recorded video, and the project led Moment Factory to create new control software, called X-Agora, which it now uses in almost all its work and licenses to operate its installations. Most people have seen Moment Factory’s work through live performances or online clips, where the impermanent becomes searchable. Millions have seen the Madonna, Jay-Z and Justin Timberlake shows, Fun at the Grammys and Arcade Fire at the Coachella festival, but video shows only part of what goes on. I had no idea that the 1,200 beach balls dropped on to the heads of the Coachella crowd changed colour with the music, or that they were tested for lethality the night before. Video can’t capture an experience designed for a space, as Moment Factory projects are, or a wind speed – Coachella – but it can convey excitement. That is what performers and marketing departments look for. The next zone contains the content team: directors, animators, illustrators, motion artists, etc. – a lot of lists on my tour end this way, with a wave of the hand. (“She was working as a graphic designer, her specialty is Photoshop. Now she’s learning 3D software …”)The freelancer philosophy repeats, by putting “somebody from video games with somebody from theatre”. This is easy in Montreal. Cirque, Ubisoft and the National Theatre School – with whom Moment Factory has run a workshop for two years – are here while tax credits protect the film and post production industry, and four universities and several colleges are growing fresh skateboarders.

In the middle of the loft is a black-curtained lab next to a final zone of programmers, lighting designers, architects and engineers. This is the only area with an obvious attempt at imposed order: a single sheet of paper requests quiet in the mornings. “It doesn’t work,” I’m told. In one corner of the lab someone is learning how to laser-scan a model of the Sagrada Familia, and in another a dozen people play with Lynx, an experimental setup combining multiple Kinects to track movement in a large space. No client for that one, yet. All projects get tested in this “black box”, which is an integral part of the studio’s process. Recently the studio decided to create a materials library, common in industrial design and architecture studios, and hired Cloé St-Cyr out of university to do it. A year later she still has to convince sales reps to send samples to a multimedia company, but her bookcase of milk crates has hundreds of catalogued materials, the behaviour of which – refractivity to fire resistance, for instance – turned out to be more important than their composition. “People just come to see me and describe what they want to do,” she says. She also produces a newsletter about new arrivals, reminding light obsessed colleagues about texture, weight and substances that react to heat. Testing was crucial for Moment Factory’s recent project for LAX’s US$1.9bn Tom Bradley International Terminal (Icon 124), the biggest and probably most complex permanent installation it has created. Some of the projections involved were so huge that they made people nauseous before they were dramatically slowed down. Moment Factory will be responsible for the interactive installations and all the content that runs on them, 24 hours a day for five years. The LAX project involved so much travel that the studio is now thinking about opening international offices. But “we are not in a rush”, Bessette says. Preserving its culture is the priority. Perhaps new employees will start out at headquarters, the way new producers now spend a few months shadowing experienced ones. “There’s nothing like proximity to your people,” Fournier adds. Other plans include increasing ownership stakes in projects, not just providing services, and focusing on public work such as the recently opened Megaphone in Montreal’s Place des Arts. This temporary amphitheatre for public debate is a good idea, but the interactive element is just a projection of the user’s sound wave on a nearby facade. Moment Factory’s reasons for doing it are more interesting. “We need to create amazing experiences, as strong as what’s on our devices, but in public spaces,” Bessette says. This argument can turn Luddite and relate to the resurgence of natural materials, craft and handwork in design. Wooded cabins with wifi or shimmering streets with touchscreens: which fantasy is more appealing? The Megaphone is also digital makeup for architecture. The facade it uses as a projection screen is part of an out-of scale building striped with windows that the city often programmes for projections. A more extreme example was Moment Factory’s projection on the Sagrada Familia in 2012. After countless illusions, the lights leave Gaudí’s facade as if it needs a coat of paint, and the last image they use is based on the architect’s drawings. Extend this to new buildings and you get the 22m-tall animated clock tower at LAX, which is physically just an elevator shaft. “When it’s off, it looks like a big rectangle,” Pontbriand says. Spectacular multimedia can compensate for blandness and enable bad design as easily as it can add layers to the beautiful. Montreal’s Quartier des Spectacles is littered with cautionary examples, but Moment Factory is one of the most sophisticated practitioners of this powerful new technique. Its best work can be very simple, too, such as a musical wall for the nearby Sainte Justine Hospital that plays the shapes you draw on it. That’s all, but it uses expertise and technology developed on bigger stages – the previous project of Nelson de Robles, the Sagrada Familia multimedia director, was for Bon Jovi. Moment Factory has set the standard in a new industry and has a target on its back. There are others doing similar work now, such as London’s Seeper, Bremen’s Urbanscreen and Montreal’s Eski Studio, a Moment Factory collaborator whose technology enabled the Coachella balls. Still, the studio is in an enviable position, assailed by international talent looking for a job and by international money looking for a moment. What’s next? They couldn’t say, but I saw a lot of binders labelled “Sochi”.

|

Words Lev Bratishenko |

|

|

||

|

|

||