|

|

||

|

The gutted interior of a chateau-style station hotel has been given sharp, sculptural furnishings to become a suitable home for a software startup Ambitious plans to resurrect abandoned heritage properties in Montreal are often greeted with guarded enthusiasm. The properties are expensive to purchase, renovation costs can be prohibitive and heritage regulations can complicate the process. In a city boasting a steady ten per cent office vacancy rate within the central business district, finding an anchor tenant to set up shop on the district’s periphery (and across from the city’s most infamous public square) may seem like wishful thinking. Gare Viger, a chateau-styled railway hotel built for the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1898, had the deck stacked against it: abandoned for 15 years, a previous effort to resurrect it came to a halt with the economic crash of 2008–09.

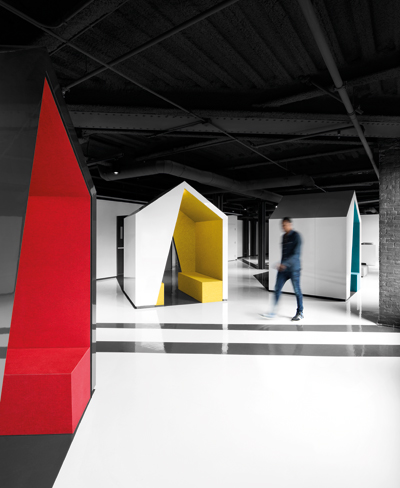

Three white-laminate privacy booths occupy the lobby A new $250 million redevelopment of the Gare Viger site was announced in the spring of 2014; the first two anchor tenants included a software development firm and a micro-brewery, both homegrown up-and-comers. Much of the building is still surrounded by scaffolding. The main entrance on Rue Saint-Antoine, once connecting the luxurious hotel with its equally well-appointed gardens, still bears the prison-like iron bars installed to keep squatters out nearly two decades ago. Walking into Lightspeed’s third-floor reception gives the impression of a modern workspace deftly inserted into the shell of an antique building, a point emphasised by an indentation between the exposed wood and brick of the building’s fabric and the new interior construction. A grotto feeling comes from the plants and tent-like meeting spaces set about a large central open space, mingling with stalactite-like steel beams. Off to the right, aquamarine back-lighting pours out from under a large rectangular table. “I see you’ve noticed our pool,” says Joan Renaud, of architecture firm ACDF. “The old Lightspeed office had a small swimming pool which we weren’t able to fully replicate here, so we came up with this.” The “pool” is in fact a large kitchen counter lined with plastic-moulded tree-stumps serving as stools.

The existing brick structure has been left untouched Lightspeed’s move to Place Viger seems almost counter-intuitive; it left a trendy neighbourhood for one of the city’s most neglected and undesirable locations. But such was the thinking a few years ago when Ubisoft set up a large studio in the similarly low-rent Mile End area and kickstarted a city-wide trend. Lightspeed’s chief revenue officer JP Chauvet explains the firm’s move was motivated by a practical need for a larger, more cohesive space, and provided a “way to get in on the ground floor, so to speak, of a part of town that’s currently on the rise”. Chauvet points to a mural of a phoenix commissioned for the office: “Old retail is dying, new retail is rising; this old building is rising too with new life.” On the floor above is a lounge with chevroned hardwood floors, classic leather sofas and chairs, antique lamps and – right in the centre – a wet bar. Renaud explained that ACDF wanted to create a space that would recall the old hotel lounge. It is located at the centre of a long, narrow and mostly open space organised to replicate the “linear voyage” of the client through Lightspeed’s services. There are no cubicles, and internal walls are kept to a minimum, so the space feels larger than it actually is. There’s also less of a contrast here between the building’s antique skin and modern guts: the brick and wooden beams feel more at home here, and give the entire floor the feeling of a university library’s attic annex. As my tour concludes I ask if they’re hiring. Chauvet and Renaud chuckle: “We get that a lot.” |

Words Taylor C Noakes

Above: The sloping wooden ceiling is the dominant feature of the attic space |

|

|

||

|

The back-lit “pool” serves as an informal meeting area |

||