|

|

||

|

Inga Sempé is not an artist. She does not want her works to be preserved in a museum, and dislikes the idea of a design with a narrative. She is interested only in creating products that people will use – objects of everyday luxury Having spent the better part of the past four days indulging in French cheese, wine and pastries, I’m rather taken aback to hear Parisian designer Inga Sempé say that the French don’t understand daily luxuries: “France is good for high-end luxury, but who cares about that? I really prefer the Italian way. It’s much more about daily life, daily pleasures: good food, good wine, being in the sun. It’s the same for design. They understand the value of the everyday.” I’ve come to visit Sempé in her studio in the 10th arrondissement of Paris, just around the corner from the Gare de l’Est. She moved into the building – a former haberdashery workshop (she thinks) – just six months ago, having previously worked from the living room of her flat on Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis a few streets away. Ethnically and economically mixed, the area has long been home to a cross-section of Parisian life, though the renovation of the Gare du Nord and incipient hipsterification – related to the increasing popularity of nearby Canal Saint-Martin and its environs – seem to be slowly edging the poorer out in favour of the artistic and middle classes. “It’s a changing neighbourhood. When I first moved to this area, people told me I shouldn’t because it was quite poor, and perceived as being rather dangerous,” Sempé says. “Now, there are more rich people arriving in the neighbourhood and I don’t think it will stay mixed for long unless the mayor steps in. I don’t like what Paris is becoming – a big shopping mall of luxury goods for foreigners.”

Blanket for Norwegian company Røros, paper models and sketches Born in Paris in 1968, Sempé grew up in an artistic household. Her father is the noted cartoonist Jean-Jacques Sempé, while her mother, Mette Ivers-Sempé, is also a successful painter and illustrator. After graduating in 1993 from Paris’s university for industrial design, ENSCI-Les Ateliers, Sempé worked with Marc Newson, among others, before starting her own studio in 2000. While she is best known for the textile-covered Ruché series for Ligne Roset and the Vapeur pleated-paper lights for Moustache, neither of these, nor her many other past projects, is on display in the studio. Perhaps because of her recent move, most of Sempé’s archive is packed away in plain, brown boxes in a loft above the studio’s small kitchen, where one of Sempé’s assistants is making us coffee. Cups in hand, we sit down to talk at a small table. There’s a green Piani desk light by the Bouroullecs to one side (Ronan Bouroullec is Sempé’s partner). The top is covered in dust and, as we talk, Sempé absent-mindedly clears it with her index finger in a neat pattern of nesting rectangles. On the other side of the table rests a series of colour sketches and tests for a rug for Golran, launching in April at Milan Furniture Fair. In fact, most of the studio is littered with various paper models of these rugs. When I ask whether someone in the office has had to scale up all the squares in the pattern by hand, she laughs and says: “I’m mean, but I’m not that mean. No, for this it isn’t necessary as we can see everything we need to see by printing it out large scale.”

Designers at work in Sempé’s light-filled studio in Paris’s 10th arrondissement

The Parisian designer poses with her Sempé w153, a clamp lamp for Wästberg, 2015 The patterns are in subtle colours with a techno-abstract feel, as if someone has taken a photograph, exaggerated the pixellation and then redrawn the exaggeration by hand in marker pen and pencil. “The design is done digitally, but of course it’s important that it doesn’t look digital,” Sempé says. “Also, these rugs are being made in Nepal. There’s a kind of compromise in the final design because they are being made by craftspeople and each one will turn out slightly differently.” Sempé says she’s fascinated by the technical processes of manufacturing and talks pragmatically, but eloquently, about the power of combining traditional craft techniques with modern technology. For example, speaking about designs for a series of blankets she has recently made for Røros, a Norwegian company, she says: “I don’t see the use of technology as preserving craft traditions. It’s not a will to preserve a culture, to keep it alive, it’s just a more efficient way to do it.” Sempé’s relentless pragmatism informs her strong interest in designing for the everyday. “I’m not interested, and never have been, in having my work bought by museums,” she says with feeling. “I’m interested in objects. I like the factories, I like the machines. I want people to use the things I make.” She is well aware of the apparent bind this puts her in with respect to current criticisms directed towards design and its relationship with what is increasingly seen as our problematic consumer culture.

Vapeur lights for Moustache, 2009

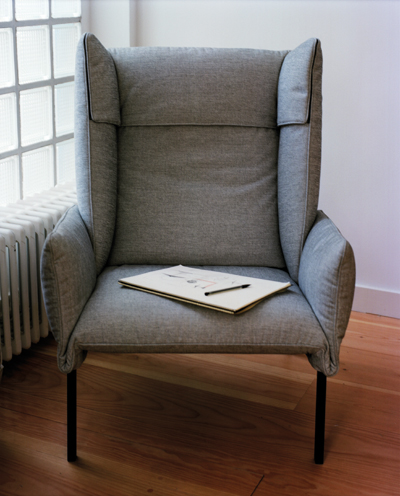

A spiral wooden staircase leads to a living space above Sempé’s studio But, she says, “if you look at our levels of production compared to the fashion industry, it’s tiny. Do we really need to change all of our clothes every six months? Of course not. It’s as much a state of mind as it is an economic choice. You don’t need to change your sofa every two years, and in that case, you don’t need to buy a sofa from Ikea. My aim is to make quality objects. It’s not to justify every curve. Anyway, we need some objects, but we don’t need to change them all the time and we don’t need so many. “I think that’s also why designers are so proud when their objects get into museums,” she continues, “because then they can be seen as artists. It’s like the highest status for a human. But I don’t care to be regarded as an artist. I grew up among artists, so I know them. They aren’t more valuable than butchers.” At this point, we get up from the table and take a quick tour of the studio. Something of a 19th-century “nail house” from the outside, inside the double-height ceilings, white walls and glass-block windows give it a pleasant feel, with plenty of light, even on this grey, rainy January afternoon. “It’s very different working here than at home,” Sempé says, “even though I do also live upstairs.” She points to the circular staircase that leads up to the first floor. “When I moved in here, people were like, ‘It’s so big. How are you going to use all that space?’ But, you only really have to plan meticulously how to use space if you haven’t got very much of it. When there’s a lot, you don’t have to think how to use it. You just use it.” Having attended Maison & Objet a few days previously, I’m curious about Beau Fixe, Sempé’s new collection for Ligne Roset, which was launched at the fair. Though Sempé is well known for her model-making process, I don’t see any of Beau Fixe in the studio, and so ask about the story behind the design, in which the structural supports of both chair and footstool cushions are visible as an exterior fixed frame. “My aim was to try to find another way to combine a structure and a cushion,” she says. “It’s not really interesting for people. I know that storytelling is really important, but, in fact, I don’t need a story to buy an object. That’s a commercial tool, a sales pitch, and it’s not really all that interesting to buy a sofa based on a story. Is it a nice sofa? Is it comfortable? Is it visually light? That’s the important thing.”

Beau Fixe armchair for Ligne Roset, 2015

Paper models of Sempé w153, a clamp lamp for Wästberg, 2015 This talk of sales pitches and marketing leads, perhaps unsurprisingly, to the problematic nature of manufacturing and commissioning design. Sempé interrupts: “I would say that there are no commissions. [Manufacturers] don’t pay you – so I would not call that a commission.” I ask whether Milan Uncut, a media campaign to expose poor royalties for designers in 2011, has had any impact, but Sempé says that by and large newspapers and magazines don’t want to talk about the subject any more. “For example, the stupid question that I often get asked by journalists is, ‘Which airline is my favourite?’ These things are so unlinked to the design world.” So, why do young people still want to be designers and why do designers continue to remain silent on the industry’s difficulties? “Most newspapers still present designers as living rock-star lifestyles, and most are unwilling to correct the assumptions because they don’t want to risk offending manufacturers and not get more work. Well, I can say it: we are not paid, we don’t have any commissions and the royalties are low.” Then how does it work? How do designers even make a living? “It only works for a few people,” Sempé explains, “because most product designers are also doing interiors or graphic design, which can hide the fact that it’s really hard to make a living as a product designer.” At this point, one of Sempé’s assistants comes over with a question about an email, and it’s clear it is time to wrap up. Thinking of how much time designers now seem to spend replying to emails, I ask how often she gets out of the studio and into the everyday world she loves so much to search for inspiration. “When I leave the studio it’s just great because I like to look at things. It’s really important, but I don’t do it enough,” she says. “I think the strangest part of this work is that you are at your desk and the machines producing your object are 2,000km away. Sometimes you visit to see how it’s going, but not very often. If you think about the Italian designers of the 1950s and 60s, they were all in Milan working in their studios, but they could just get in their cars to drive to the factories. It was so much more direct. That’s the way to do things.” This article first appeared in our Studios issue, which also features interviews with David Adjaye, Frank Gehry and Michael Young |

Words Crystal Bennes

Photography François Coquerel |

|

|

||

|

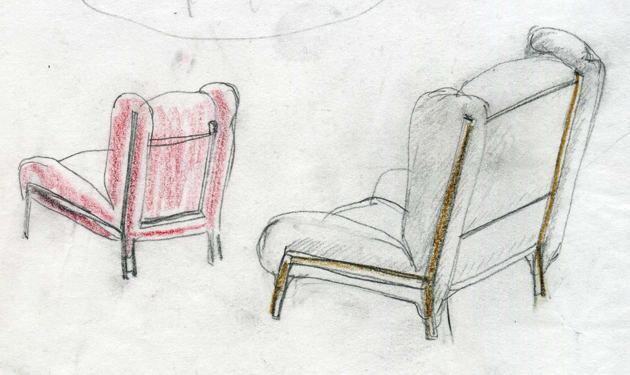

Sketches for Beau Fixe, Ligne Roset, 2015 |

||