|

|

||

|

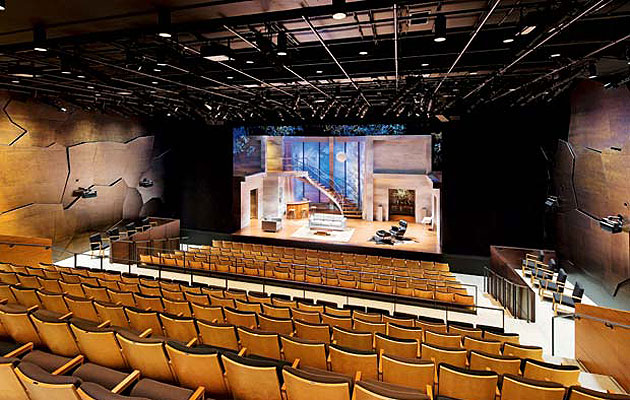

ICON The Signature Center is the biggest arts complex in New York since Lincoln Center, but its $66m budget was far smaller. FG I think [founder] Jim Houghton’s intent was always to do something not very pretentious so, as you mentioned in your original article (Icon 108), I’ve been doing that all my life! I think that people would think that Bilbao was an expensive building but it wasn’t; it’s hard for people to understand that it wasn’t, but Bilbao was done in the spirit of Signature Center. It was built for $100m – that was $300 per square foot. So just because it looks more complete, it was not an expensive building. The only building I have done that gets into the fancier thing was Disney Hall because it was required by the board; they wanted brass handrails and things like that. ICON I like the way the design takes you back to your early plywood, concrete and glass architecture of the 1978 extension to your Santa Monica house. FG Yes and I’m doing it again on a new house. We’re designing another house; at my age, I should be moving into an old age home but I got my son, who’s studying architecture, to design a house for me. It’s wood and plywood, so you’ll be happy. ICON Well, I thought those utilitarian materials really added to the unpretentious feel of the interiors of the Signature Center; it was very raw. FG The most important thing for me is the feeling of it; that there’s kind of a sense of place and that there is some humanity to it, and that the spaces aid an intimacy between the users. I think that’s more important than what you make it out of. I see so many inhuman, heartless buildings being built by all sorts of people all over the world and it’s stupid. ICON How did you differentiate between the Signature’s three theatres, which I thought all really successfully focused the energy of the space towards the stage? FG Well, it’s the same feelings I had with Disney Hall, the relationship between performer and audience is the crucial element, and if you go back to the old bard, you know, “All the world’s a stage”. So it’s the most important thing in every building, to create the place for human interaction. In theatre it’s more contrived because it’s a separation of talents: the commissioner, the viewer and the performer. But I think it’s similar in all walks of life. I think that humanistic thing, it’s magical when you do it right and I love that. Man, I try to make that happen! I mean that’s the greatest – if I go down in history, I want to be known for doing that.

ICON When I visited, the set designers of all three plays had deconstructed the architecture of the theatres in different ways, and I was quite interested in whether that was hard for you, when you designed the set for Don Giovanni at Disney Hall, to make an intervention into your own architecture? FG Well, my set was perverse; I did crumpled paper. I don’t design with crumpled paper; everybody thinks that I do because of The Simpsons – it was an easy shot, so they could make fun of me. But the director started talking about Don Giovanni’s mind and he said it’s in the clouds, and blah, blah, blah. And I was crumpling paper to fill the stage and before you knew it we had a set. ICON Your line drawings are enlarged and decorate one of the corridors in the theatre. If you don’t design with crumpled paper, how do ideas develop from these sketches? FG The crazy thing is, over the years when you see the finished buildings and you look at the first sketches, a lot of it’s there. So I just trust my intuition and draw. I don’t take my pen off the paper, I just keep going and I do lots of them and it evolves over 20 drawings, you start to get the beginnings of an idea of how to do it. But I can only do it once I see the block models that show the volumes; so the volumes that we have to work with are pretty clear in my head and I’ve seen the site and I understand the problems. It’s not something you can do without a lot of forethought. ICON That’s what I was interested in, the modelling process; I kind of thought that came afterwards, rather than before. But you define the programmes in coloured blocks, is that right? FG Yes, coloured wood blocks, and we just pile them up and move them around until we get what we think is an organisation of how the rooms and things should work, and a volumetric sketch of how the thing sits on the site with its neighbours. You sort of draft the visuals before you do anything and that can only happen if you understand the programme in great detail. I get blamed for building a building and stuffing things in that shape and I think a lot of architects are doing that today, but I don’t do that. By the time the shape is being formed, it’s very close to the bone of the programme and we check with a computer to make sure the volumes are what we need them to be – for budget control – all along, from the beginning. ICON What is the importance of using wooden blocks rather than a computer? FG Well, that’s the way we’ve been doing it and the problem with the computer is it dries out all of the humanity and it takes away all the feeling. I’m an old guy … but I am trying to design on the computer. I haven’t seen anything that excited me coming out of the computer stuff. A lot of people are trying but it sort of looks repetitive; sort of like the language of Rhino or Maya or those systems. ICON You say that creative play has been lost in architecture. Is that an inherent part of this modelling process? FG Well, creative play for me is letting your intuition express itself, but in a knowledgeable, not haphazard way. I mean, we do a lot of planning before, to get there. I can’t try to stress that enough: we understand the programme before I move; we understand the scale, you know, all of those things, so we’re within budget for the volumes and all that stuff. And once I’ve got that in my head, my drawings get very close to the skin of what kind of a building we can afford. So some of it’s sketching, some of it’s models, it’s back and forth. The end has to be perfect. I don’t build it unless it clicks – you know, when you get the combination on the safe and you hear it click, that’s what I look for. You see it, you feel it and then you know you’re there.

ICON You’ve spoken about the special thrill of building in New York, where your father was brought up in Hell’s Kitchen. Why did it take you so long to build there? With your skyscraper at 8 Spruce Street and the Signature Center you’ve had a great New York year. FG I did the IAC Building too. In fact, my first NY project was the Condé Nast cafeteria. But I don’t know why it took so long. Richard Meier lived in New York for all those years and never got a building for a long time. I think most cities are built by people who have no sense of human responsibility. So wherever you go in the world, the built environment is mostly heartless. People fight back in places like Greenwich Village where they build their own infrastructure and change that feeling by small, small efforts, and we go there and love that. But the corporate world doesn’t do that, it stays cruel and heartless. |

Image James Ewing/Otto

Words Christopher Turner |

|

|

||