|

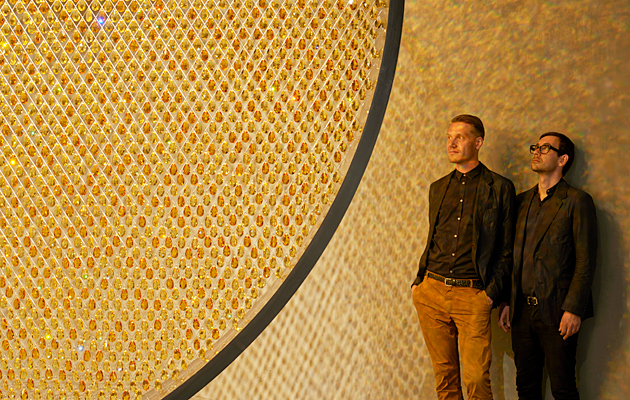

The London-based design duo has worked with Swarovski to create a glittering artificial sun using 8,000 topaz crystal droplets, on display at Design Miami/Basel At Design Miami/Basel, the London-based design duo exhibit Prologue, their eighth collaboration with Swarovski. At 4m high, it holds more than 8,000 topaz crystal chandelier droplets that together create a golden, shimmering artificial sun. Icon sat down with Patrik Fredrikson and Ian Stallard at the fair to discuss the glittering installation and their new furniture pieces on display at the David Gill booth. Someone described Prologue to me as meta-bling. Were you ever worried that the piece might be overwhelming, too much? Crystal can become overwhelming if merely used to be bling. But, with Prologue, it isn’t there for decoration – it is supposed to create an impression of the sun and I don’t think any representation of the sun can be overwhelming. It could never be bright enough. If you cut anything at sharp angles, even metal, it would be bling, but that’s what draws people in. That’s what’s really amazing to people, that’s what’s awe-inspiring. And though we’ve been working with crystal for some years now, it’s something we only have limited control over. In daylight, the two different shades of gold produce violet and blue, which is unexpected – they’re so efficient at refracting light.

You’ve worked with Swarovski before, in 2011 – a collaboration that resulted in Iris. Can you describe that piece and how the experience of making it fed into Prologue? This is, I think, our eighth collaboration with Swarovski. Iris is important because whenever we use any material, including crystal, it has to be integral to the piece – it has to be there for a reason. Crystals are lenses, so with Iris the thought was to use them to make the ultimate lens, which is of course the eye. Shown in the context of Design Miami, it was important that they were neither products nor sculptures, but something in between. They are strong, but they can exist in each world quite happily. Prologue was first shown at Art Basel/Hong Kong in the courtyard of the former Police Married Quarters. How does this version differ? PMQ, as they call it, is a very interesting space that is being converted into a design hub. Prologue was first shown there in the courtyard of an art deco block, displayed outside, resting on two steel construction beams. Here in Switzerland it’s inside, shown suspended from an RSJ, which gives it a new energy and movement. In Hong Kong we allowed it to rust, so the city ate into it, and people touched it, so their handprints became part of the piece. Here, that was all removed – its layer of history was taken away and it was given a new life. It’s hanging like a work in a gallery rather that sitting in the jungle of the city. In your literature you talk a lot about primeval emotion. What effect were you hoping to conjure in the viewer with the piece? It’s a simple emotional form. There is something very calming and moving, that draws people to a representation of the sun. One only has to look at Olafur Eliasson’s sun in Tate Modern’s turbine hall to understand that. It’s interesting because people do spend a lot of time with it. One phenomenon that we really didn’t expect was the selfie. And this has happened both in China and here. People feel compelled to take selflies in front of it. You’ll notice that they haven’t done that with any of the other installations here. It hits you right in the middle from the first moment you see it.

Did you visit the Swarovski factory for this piece? Are they bespoke or ready-made parts? We’ve visited the factory in Wattens, Austria, a number of times, but these are chandelier components, traditional pear-shaped crystal. They were designed as reflective lenses to amplify candlelight, so it’s nice to use this old design – they have these strange links to the piece as it is now. At the David Gill booth you’re also launching the Detroit table, which resembles one of John Chamberlain’s crushed car sculptures. It’s part of the wider collection that we do with David Gill Gallery. With all our work we like to let materials do what they do best, so with metal we’re forming it but we’re allowing it to have some say in the process itself. We’re crushing it, and we have some kind of idea where we want it to go, but it will also behave in a way that is natural to the metal and, in that sense, it looks effortless. In fact, if anything, it’s incredibly difficult to form something like that in a way that is aesthetically pleasing and interesting without faking it. And it’s not fake – a huge amount of craftsmanship and skill goes into it. We’re making furniture, not art, and this is a completely different thing. It has to have a beautiful fluidity to it and functionality as well. |

Words Christopher Turner |

|

|

||

|

|

||