Twenty-five years ago, a group of young, unknown Dutch designers took Milan by storm with a stance that was ‘anti-luxury, anti-formal and anti-product’. Their influence is still shaping European design practice two decades later, writes Peter Smisek.

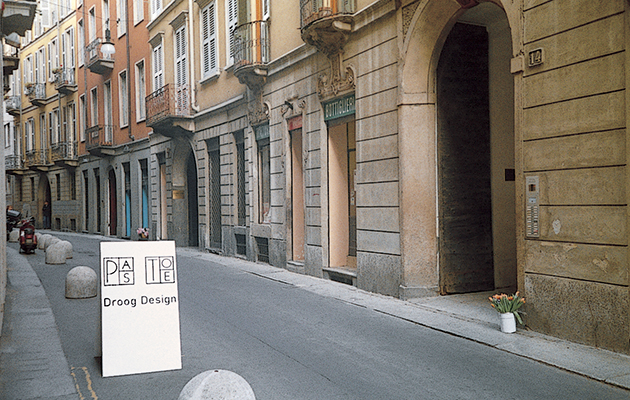

A quarter of a century ago, a group of young product designers were hand- picked by art historian Renny Ramakers and designer Gijs Bakker to present their work alongside Dutch furniture manufacturer Pastoe in Milan. Pastoe had been a mainstay on the Dutch design scene since earning its reputation for no- nonsense, made-to-order cabinets in the 1950s. But it was this select group of young designers – some students, some recent graduates – who captured the moment. Under the single moniker ‘Droog’ (it means ‘dry’ in Dutch and is pronounced droagh by clearing your throat at the end), these individuals – Hella Jongerius, Marcel Wanders, Piet Hein Eek, Tejo Remy, Jurgen Bey, Richard Hutten and others – would go on to shape Dutch design thinking, and indeed international design practice, for the next two decades.

Prior to Droog’s debut, Milan was in the grip of Memphis: bold, brash, colourful, laden with historical and cultural allusions. Democratic design, championed by mid-mod designers, had been replaced by a renewed interest in form that ultimately led to opulence. Droog made no pretences to being either. ‘Our stance was against these traditional standards, and against this terrible idea of luxury in design,’ says Bakker. Droog was pure concept. It was anti-luxury, anti-formal, anti-product. And it never aspired to be a mass-market phenomenon – though it unwittingly helped to spawn the excesses of today’s design-art market. And it caught on, with the modest exhibition attracting growing crowds as the Salone wore on. Rave reviews followed. Dutch design would never be the same again. The lasting testament to the movement’s influence exactly 25 years on is that design discourse, and much of its production, is still shaped by the same ethos that propelled these relative unknowns to international success.

Tejo Remy’s Rug chair for Droog. Photo: Droog Design Amsterdam

Tejo Remy’s Rug chair for Droog. Photo: Droog Design Amsterdam

Droog did not spring from nowhere, of course. Ramakers, an art historian by education and a design critic and journalist by trade, was the editor of Items magazine at the time, and had put on a number of successful group shows of emerging Dutch talent before the big outing in Milan in April 1993. The final dry run, organised by Ramakers in Amsterdam in February, was entitled ‘Een middag gewoon doen’. A more-or-less literal translation of this would be ‘an ordinary afternoon’, albeit with knowing Calvinist connotations of normalcy and plainness as a kind of moral decency, slyly contradicting the group’s droll, surreal and individual take on design. Still, many observers, designer Andrea Branzi among them, noted that Droog displayed signs of Protestantism: a fiercely unostentatious, provocative and probing logic. These attitudes were not dissimilar to those of the Netherlands’ architectural renaissance of the late 1980s and 90s.

Much like other western economies, the Netherlands went through a period of de-industrialisation in the 1980s. Furniture manufacturers such as Pastoe, Bruynzeel, Gispen and Ahrend were well-established at home, but did not achieve major international success. ‘Dutch design was overlooked and overruled by Scandinavia and Italy and by the late 1980s, industry was being outsourced to lower income countries; first to Poland and Portugal and later to China,’ says Bakker, who also taught at the design school in Eindhoven at the time. The shift left many young graduates and even veteran designers such as Bakker – who got his big break in the late 1960s with a collection of avant-garde jewellery – without secure employment. However, this era also saw significant support for the Dutch creative industries in the form of a relatively generous system of government grants. This didn’t mean young designers became rich overnight, and Droog was itself established as a non-profit foundation anyway, but people could get by. This enabled what Bakker calls a ‘generation of self-producing designers’ – or, as Richard Hutten called them, ‘young punks’ – to create small editions of prototype designs that were never really intended for a mass market.

![]() Gijs Dakker’s Chair with Teju Remy’s Milkbottle lamps at the 1993 Milan Salone

Gijs Dakker’s Chair with Teju Remy’s Milkbottle lamps at the 1993 Milan Salone

The self-production phenomenon was not solely con ned to the Netherlands: Ron Arad, Marc Newson and Tom Dixon were creating experimental, hand-made products along similar lines. The genius of Droog was to create a coherent narrative around these alternative practices, while also managing to contain a broad range of personalities and approaches. From its inception, Droog effortlessly combined the environmentalist and self-assembly attitudes of Tejo Remy and Piet Hein Eek with the more whimsical tendencies of Marcel Wanders and Jurgen Bey.

Remy’s Rag Chair and Chest of Drawers, both by Remy and two of the early icons design. ‘My idea was creating my own paradise, in a Robinson Crusoe-like way, making do with objects that I could nd and that were readily available,’ says the designer, talking about the chair, which was in fact his graduation project from 1988. Unwanted, unfashionable clothes are laid out in layers and bound into a robust seat. Ditto the Chest of Drawers, in which a number of disparate drawers are stacked and bound by a piece of cable.

![]() More Droog, including the Hanging Wadrobe at the 1993 Milan show

More Droog, including the Hanging Wadrobe at the 1993 Milan show

Eek’s contribution, the Scrapwood Cabinet, was conceived and executed along similar lines. Bakker’s Chair with Holes, meanwhile, was a rigorous study in incrementally reducing a chair’s mass while taking into account its structural logic. Wanders contributed with his Set Up Shade lamp, reducing the object’s function and form to a single plain lampshade, and then stacking these for good measure. It wasn’t all lofty ideals or playful whimsy either – the young participants were well aware that their youthful vigour and fresh take were highly marketable. After their graduation, Hutten recalls Hella Jongerius, another core Droog associate, saying: ‘OK, how can we turn this into some money?’

Bringing a range of styles and conceptual approaches under a single umbrella paid off, and over the years, Ramakers and Bakker provided a platform for many other young designers. In 1994, Peter van der Jagt designed the Bottoms Up Doorbell, which embraced the anti-product, found-object aesthetic while questioning what goes on inside the black- box of most electronics. Later Marijn van der Poll’s 2000 Do Hit Chair, a steel cube that the owner is meant to bash into a seat with a sledgehammer, was an aggressive investigation of the boundaries between the creative and the destructive act, as well as a comment on standardisation versus customisation. A more mainstream acceptance of the group’s aesthetic was the use of their work in a new cafe at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

![]() Droog Candlesticks at the 1993 Milan show

Droog Candlesticks at the 1993 Milan show

In its heyday, Droog’s associated designers engaged with emerging technology in highly novel ways. A series of workshops in the latter half of the 1990s, entitled Dry-Tech, paired the designers with material researchers from Dutch universities. One of the most memorable collaborations was Wanders’ Knotted Chair – a macramé tapestry made of aramid cords and carbon bre impregnated with epoxy resin. The piece is now included in the permanent collections of MoMA, the V&A, and Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum. According to Bakker, it may be Droog’s, and Wanders’ most significant achievement: handmade and high-tech, strange yet familiar; a throwback, yet completely of its time.

By the mid 2000s however, Droog had run out of steam. In 1997, the Akademie Industriële Vormgeving Eindhoven (Academy of Industrial Design) changed its name to the now ubiquitously international Design Academy Eindhoven and in 1999, trend forecaster Li Edelkoort became the school’s director. From 2002, the city’s Dutch Design Week brought together each year’s graduates, essentially institutionalising a role previously played by Droog. In 2009, Bakker quit Droog over Ramakers’ decision to open a shop in New York. ‘Creativity and originality of Droog Design products have always been a first condition for me. The shop means the commercial element is now the main goal,’ he wrote.

The New York shop failed and closed a year later. Pop-ups in Las Vegas and Hong Kong followed, but Droog’s space is now in central Amsterdam, featuring as exhibitio space, a one-room hotel and a shop. Droog design still has its fans, but it is often treated as a curiosity of recent history. Under Ramakers’ solo leadership, Droog continues its curation and consultancy, and does it well. In 2015, it once again caused a stir in Milan with Construct Me!, a tongue-in cheek look at the nuts and bolts of furniture-making. The show won a Milano Design Award, reminding the industry that the brand is still a force to be reckoned with.

![]() ‘Anti-luxury, anti-formal and ‘anti-product’- Droog in Milan 1993

‘Anti-luxury, anti-formal and ‘anti-product’- Droog in Milan 1993

The ubiquity of conceptual design-as-art though means that Droog has lost its unique selling point. Indeed, Wendy Plomp, the curator of designers’ collective Dutch Invertuals cites Edelkoort and the Design Academy, rather than Droog, as the more powerful, forward-looking influence in this respect. Even so, she agrees that Droog essentially kickstarted the ‘Dutch design’ phenomenon and paved the way for a younger generation of Eindhoven alumnae. The Droog ethos has trickled down to other European design schools, too. Designs meant to ‘start a conversation’ or those tailored to a designer’s ‘fascination’ are now commonplace. So much so that they sometimes result in conversations that aren’t worth having. The design-art market is now saturated with Dutch designers of a certain age, as well as increasingly young ones, plus Newson and Arad and host of others. Together with Droog, they’ve had a hand, inadvertently, in creating the art-like market for contemporary design, for better or for worse. When I asked Ramakers whether Droog would be presenting in Milan this year, the answer was a definitive ‘no’. But it doesn’t matter. Because Droog – or as Hutten called it ‘the last design movement after Memphis’ – will actually be there in spades.