|

|

||

|

Thinkers in art, technology, fashion and product design are responding to the threat of mass surveillance with a range of privacy-conscious gadgets that have a distinctly villainous aesthetic In June 2013, Edward Snowden made the headlines with his revelations about the US National Security Agency’s surveillance programmes. The documents he presented to the media revealed the agency’s tactics for mass surveillance and the bulk collecting of civilian telephone data provided by communications companies. In the year or so since, the topic has been in and out of the news, fuelling periodic bursts of outrage and speculation that dissipate into a general unease about how the information we share is being used. Thinkers in art, technology, fashion and product design have been channelling the privacy issue into physical and digital form: together, their works present a strange and possibly prophetic survival kit for the surveillance state.

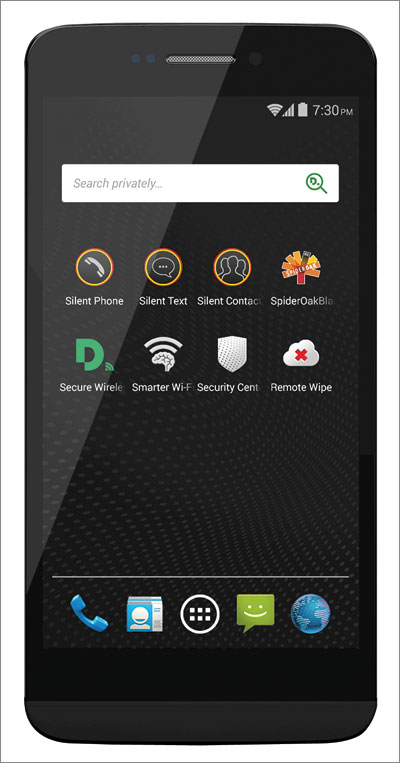

Silent Circle’s Blackphone encrypts calls, texts and browsing “People always knew the government could do something like this, but they didn’t realise it was actually doing so – and at such a broad level,” says Vic Hyder, former US navy SEAL and chief operations officer of Blackphone, a security-minded smartphone that keeps its user safe from interceptions and data leakage. “I read this week about the NSA blanket-collecting all cellular traffic in the Caribbean. The entire Caribbean. And, with data memory these days, information doesn’t have to be sifted through daily. It can be collected and stored for up to ten years. When I win the lottery or run for president, that information will be there to be searched.” Blackphone, launched by private communications company Silent Circle this August, is the first commercially available phone to encrypt calls, texts and internet browsing. Despite the stealthy name, it looks like any Android phone: a sleek black handset with a familiar interface. Hyder says the phone, which costs about $630, is designed for individuals concerned about privacy, corporate enterprises and – paradoxically – government agencies. Apart from its secure software, Blackphone’s most effective feature is almost unbelievably simple. “When you install Facebook’s app and it requests access to your contacts, location, photos and so on, you have a default Blackphone setting that turns that access off until you specify that it should be turned on, so you’re not sharing when you don’t want to be sharing,” Hyder says. “To use most apps you have to accept the terms and conditions in their entirety. It’s an all or nothing deal.”

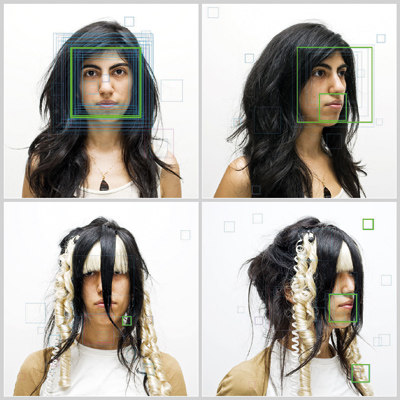

Jammer Coat by Coop Himmelb(l)au While Silent Circle’s ambition seems to be to turn Blackphone into a mainstream brand for the privacy-conscious – the company has customers in more than 150 countries – other responses to the NSA revelations have resulted in an angrier, more extreme kind of counterculture. Brooklyn-based artist Adam Harvey has been exploring the outward facets of counter-surveillance since 2001, when the introduction of the US Patriot Act, a set of counter-terrorism laws, led him to think about the loss of civil liberties. “I wondered how fashion could be used to increase personal privacy and reclaim some of those liberties we’ve lost,” he says. “If you’re travelling somewhere or if the weather changes, you use dress to adapt yourself to those conditions. We should be able to modify how we look and behave according to this new environment of ubiquitous surveillance.” Harvey’s investigations have led to a suite of semi-speculative products and designs that are a chilling mix of the impossibly far-fetched and the probably quite useful. These include the Anti-Paparazzi Clutch, a bag that obscures the wearer’s face by emitting a beam of bright light that cancels a camera flashbulb; the Off Pocket, a pouch that blocks signals from a mobile phone when it is out of use; the Anti-Drone Burqa, a cover of reflective material that counteracts thermal imaging; CV Dazzle, a set of face-painting patterns that allows the wearer to go undetected by facial recognition software; and a copper wallet insert that prevents your credit cards being skimmed by radio frequency identification (RFID). These objects are part of Privacy Gift Shop, an installation set up at the New Museum in New York in September.

The bunker near Stockholm that stores WikiLeaks’ servers “On one hand, they seem like radical concepts but, on the other, they should be expected,” he says. “It’s a common trope to raise questions with art, but it’s more interesting when you can hint at solutions.” A central part of his research is following military defence blogs and “keeping tabs on what technologies may emerge”. In the case of the Anti-Drone Burqa, he noticed a large DARPA grant for developing a thermal imaging camera capable of capturing images from long distances in extremely high resolution. “I thought about the typical path that would follow if a camera like this became ubiquitous and what could be done to hide from it.” The burqa made its point: a splash on the military blogs for finding a loophole not seen by those developing their costly thermal imaging cameras and in the press for its political provocations. But other projects live on with seemingly increasing pertinence. “CV Dazzle started out speculatively. It was a crazy idea that I wasn’t even sure it was possible to do. But a few months ago a reporter from the LA Times told me it’s now become a trend for the post-Snowden generation. People dress up like this and throw parties. That’s pretty amazing.” It is similar to punk or any other fashion movement celebrating a common ideology, Harvey says. “The look of CV Dazzle was inspired by the party scene around Boombox in London. It’s a club aesthetic that allows you to be recognised by a certain type of person but not others – in this case, machines. There’s a dual perception of aesthetic emerging I guess.”

Listening device Conversnitch takes snatches of conversation recorded in public and private spaces and broadcasts them as tweets By bringing the online privacy issue into the physical realm, Harvey’s work raises an interesting question about aesthetics. If his and others’ designs are for the protection of normal people with normal concerns (and not facilitating a criminal underbelly as could easily be construed), why should they look so villainous and stealthy? Why is the “Blackphone” not the “Safephone”? In 2010, we saw photos of the granite “bat cave” outside Stockholm where WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange stores his servers – any secure building could have done the job, but he chose a bunker with the look of a Bond-villain lair. Such an image problem around privacy-conscious design doesn’t support the idea that it isn’t just for the criminal or paranoid, but for the improvement of everyone’s lives. Austrian architect Coop Himmelb(l)au also had a shady look in mind for Jammer Coat, a modern-day invisibility cloak designed for Workwear, an exhibition at Milan’s Triennale Design Museum in June. The bulky coat is made of tightly woven metallised fabric that works as a personal Faraday cage: phones and tablets concealed in interior pockets are shielded from electromagnetic fields; irregular, bulging ripples of padded fabric serve to obscure the user’s body shape; further visual distortion is provided by patterns of dots that vary in size over the sheeny fabric, similar to the dazzle camouflage painted on battleships in during the first world war. When designing the Cloak app, it wasn’t the prying eyes of the government and data-hungry tech companies that Brian Moore and Chris Baker were trying to avoid. Rather, it was Moore’s ex-girlfriend. The “anti-social networking” app takes location data from the mobile devices of your friends and tells you when they are near, helping you steer clear of awkward situations. The app, which started as a bit of fun but has now been downloaded 400,000 times, features maps rendered in a night-vision palette of green and black, with nearby users’ movements appearing like dots on a radar. The pair say they are re-branding the app to show it can do the opposite: show a user where their friends are in order to meet up. “I’m a social person. I like to know where my friends are, and I’m okay with them knowing where I am,” Moore says. “Obviously there are times when you don’t want to see certain people, but you should always have the ability to switch this knowledge, this technological awareness, on and off. It’s about control.” Vic Hyder also says that protecting your life from data exploitation doesn’t mean “hiding under your bed and avoiding everyone” but greater choice and control. “It’s not about creating paranoia, because this is already a reality. To exist in the modern world means you have to give up data. I shop on Amazon and I use social media, but it’s a trade-off – a trade I consciously make. We’re trying to create more awareness about what you’re giving up when you do that trade.”

Adam Harvey is researching ways to fool facial recognition software Making people aware of the ease of snooping is the aim of Conversnitch, by American artists Brian House and Kyle McDonald. The listening device takes snatches of conversation recorded in libraries, lobbies, parks, fast-food joints – and even bedrooms – and broadcasts them as tweets. “The idea of confusing public and private space we thought was really compelling,” says House, an adjunct professor at Rhode Island School of Design. “What do those terms mean in a world where we use mobile devices all the time and security cameras are following us everywhere?” The device, conceived for Prism Breakup, an art and technology workshop at Eyebeam, New York in October 2013, can be made simply using a Raspberry Pi and fits into a light socket as a power source. “We did this using off-the-shelf products for under $100. If we can do that as independent artists, corporate or tech interests with a lot of resources can do so much more. In doing something quickly, publicly and easily and spurring people to be uncomfortable about it, the hope is to make them uncomfortable about all the other things that could be happening unquestioned.” Perhaps you’re reading this wondering why mass data collection is a problem at all. That, if you have done nothing wrong, you have nothing to hide. And, in the case of the tech corporations, that the odd targeted ad or spam newsletter is a small price to pay for making international video calls, communicating instantly or being able to buy something with one click.

“Anti-social networking” app Cloak helps you avoid people What should trouble us is the lawless tangle that exists around the issue and its struggle to keep up with the speed of the technology industry. With no defined set of rules regarding the information we willingly give up online – something like Tim Berners-Lee’s proposed Internet Bill of Rights – we face an era where our personal data stock can be forever mined: the low fitness your wristband reveals pushing up your health insurance premium or a hasty tweet from years ago preventing you getting your next job. Even if you don’t object to your data being stored, you may not be thrilled by the idea of third parties making money from it. The legalities of the data broker business – selling packages of personal information with names removed, to marketing companies – are similarly ill-defined. We now share so much data about ourselves that, by combining different sources, it’s possible to trace those packages back to real people, real homes and real property, all of which is clearly protected by law. Hyder says the next generation is already much more aware of its online exposure. “My email account is just my name, but my son uses a pseudonym for everything. The culture is leading towards more respect for privacy, and protecting yourself as you go along. Because mistakes made these days are saved forever.” This article first appeared in Icon’s December 2014 issue: Data, under the headline “Dark Matter”. Buy back issues or subscribe to the magazine for more like this |

Words Riya Patel

Image above: Adam Harvey’s Anti-Drone Burqa counteracts thermal imaging

Images: Markus Pillhofer, Adam Harvey, Åke E:Son Lindman |

|

|

||