|

|

||

|

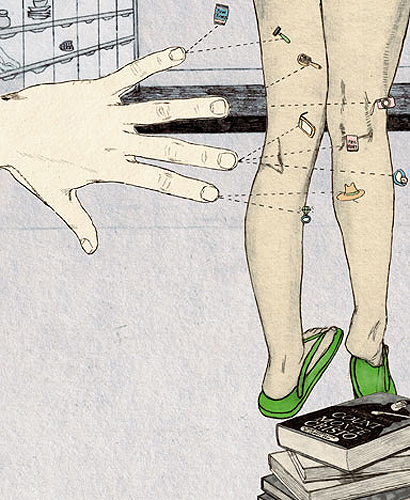

Tjan was in the condo when she got home and he spotted her from the balcony, where he’d been sunning himself and helped her bring up her suitcases of things she couldn’t bear to put in storage. “Come down to our place for a cup of coffee once you’re settled in,” he said, leaving her. She sluiced off the airplane grease that had filled her pores on the long flight from San Jose to Miami and changed into a cheap sun-dress and a pair of flip-flops that she’d bought at the Thunderbird Flea Market and headed down to their place. Tjan opened the door with a flourish and she stepped in and stopped short. When she’d left, the place had been a reflection of their jumbled lives: gizmos, dishes, parts, tools and clothes strewn everywhere in a kind of joyful, eye-watering hyper-mess, like an enormous kitchen junk-drawer. Now the place was spotless – and what’s more, it was minimalist. The floor was not only clean, it was visible. Lining the walls were translucent white plastic tubs stacked to the ceiling. “You like it?” “It’s amazing,” she said. “Like Ikea meets Barbarella. What happened here?” Tjan did a little two-step. “It was Lester’s idea. Have a look in the boxes.” She pulled a couple of the tubs out. They were jam-packed with books, tools, cruft and crud – all the crap that had previously cluttered the shelves and the floor and the sofa and the coffee table. “Watch this,” he said. He unvelcroed a wireless keyboard from the side of the TV and began to type: T-H-E C-O … The field autocompleted itself: THE COUNT OF MONTE CRISTO, and brought up a picture of a beaten-up paperback along with links to web-stores, reviews, and the full text. Tjan gestured with his chin and she saw that the front of one of the tubs was pulsing with a soft blue glow. Tjan went and pulled open the tub and fished for a second before producing the book. “Try it,” he said, handing her the keyboard. She began to type experimentally: U-N and up came UNDERWEAR (14). “No way,” she said. “Way,” Tjan said, and hit return, bringing up a thumbnail gallery of fourteen pairs of underwear. He tabbed over each, picked out a pair of Simpsons boxers, and hit return. A different tub started glowing. “Lester finally found a socially beneficial use for RFIDs. We’re going to get rich!” “I don’t think I understand,” she said. “Come on,” he said. “Let’s get to the junkyard. Lester explains this really well.” He did, too, losing all of the shyness she remembered, his eyes glowing, his sausage-thick fingers dancing. “Have you ever alphabetised your hard drive? I mean, have you ever spent any time concerning yourself with where on your hard drive your files are stored, which sectors contain which files? Computers abstract away the tedious, physical properties of files and leave us with handles that we use to persistently refer to them, regardless of which part of the hard drive currently holds those particular bits. So I thought, with RFIDs, you could do this with the real world, just tag everything and have your furniture keep track of where it is. “One of the big barriers to roommate harmony is the correct disposition of stuff. When you leave your book on the sofa, I have to move it before I can sit down and watch TV. Then you come after me and ask me where I put your book. Then we have a fight. There’s stuff that you don’t know where it goes, and stuff that you don’t know where it’s been put, and stuff that has nowhere to put it. But with tags and a smart chest of drawers, you can just put your stuff wherever there’s room and ask the physical space to keep track of what’s where from moment to moment. “There’s still the problem of getting everything tagged and described, but that’s a service business opportunity, and where you’ve got other shared identifiers like ISBNs you could use a cameraphone to snap the bar-codes and look them up against public databases. The whole thing could be coordinated around ‘spring cleaning’ events where you go through your stuff and photograph it, tag it, describe it – good for your insurance and for forensics if you get robbed, too.” He stopped and beamed, folding his fingers over his belly. “So, that’s it, basically.” Perry slapped him on the shoulder and Tjan drummed his forefingers like a heavy-metal drummer on the side of the workbench they were gathered around. They were all waiting for her. “Well, it’s very cool,” she said, at last. “But, the whole white-plastic-tub thing. It makes your apartment look like an Ikea showroom. Kind of inhumanly minimalist. We’re Americans, we like celebrating our stuff.” “Well, OK, fair enough,” Lester said, nodding. “You don’t have to put everything away, of course. And you can still have all the decor you want. This is about clutter control.” “Exactly,” Perry said. “Come check out Lester’s lab.” “OK, this is pretty perfect,” Suzanne said. The clutter was gone, disappeared into the white tubs that were stacked high on every shelf, leaving the work-surfaces clear. But Lester’s works-in-progress, his keepsakes, his sculptures and triptychs were still out, looking like venerated museum pieces in the stark tidiness that prevailed otherwise. Tjan took her through the spreadsheets. “There are ten teams that do closet-organising in the network, and a bunch of shippers, packers, movers, and storage experts. A few furniture companies. We adopted the interface from some free software inventory-management apps that were built for illiterate service employees. Lots of big pictures and autocompletion. And we’ve bought a hundred RFID printers from a company that was so grateful for a new customer that they’re shipping us 150 of them, so we can print these things at about a million per hour. The plan is to start our sales through the consultants at the same time as we start showing at trade-shows for furniture companies. We’ve already got a huge order from a couple of local old-folks’ homes.” They walked to the IHOP to have a celebratory lunch. Being back in Florida felt just right to her. Francis, the leader of the paramilitary wing of the AARP, threw them a salute and blew her a kiss, and even Lester’s nursing junkie friend seemed to be in a good mood. When they were done, they brought take-out bags for the junkie and Francis in the shantytown. “I want to make some technology for those guys,” Perry said as they sat in front of Francis’s RV drinking cowboy coffee cooked over a banked wood-stove off to one side. “Room-mate-ware for homeless people.” Francis uncrossed his bony ankles and scratched at his mosquito bites. “A lot of people think that we don’t buy stuff, but it’s not true,” he said. “I shop hard for bargains, but there’s lots of stuff I spend more on because of my lifestyle than I would if I had a real house and steady electricity. When I had a chest-freezer, I could bulk buy ground round for about a tenth of what I pay now when I go to the grocery store and get enough for one night’s dinner. The alternative is using propane to keep the fridge going overnight, and that’s not cheap, either. So I’m a kind of premium customer. Back at Boeing, we loved the people who made small orders, because we could charge them such a premium for custom work, while the big airlines wanted stuff done so cheap that half the time we lost money on the deal.” Perry nodded. “There you have it – roommate-ware for homeless people, a great and untapped market.” Suzanne cocked her head and looked at him. “You’re sounding awfully commerce-oriented for a pure and unsullied engineer, you know?” He ducked his head and grinned and looked about twelve years old. “It’s infectious. Those little kitchen gnomes, we sold nearly a half-million of those things, not to mention all the spin-offs. That’s a half-million lives – a half-million households – that we changed just by thinking up something cool and making it real. These RFID things of Lester’s – we’ll sign a couple million customers with those. People will change everything about how they live from moment to moment because of something Lester thought up in my junkyard over there.” “Well, there’s thirty million of us living in what the social workers call ‘marginal housing’,” Francis said, grinning wryly. He had a funny smile that Suzanne had found adorable until he explained that he had an untreated dental abscess that he couldn’t afford to get fixed. “So that’s a lot of difference you could make.” “Yeah,” Perry said. “Yeah, it sure is.”

Extracted from Makers, by Cory Doctorow, HarperVoyager, £14.99 |

Image Anna Higgie Words Cory Doctorow |

|

|

||