|

|

||

|

Polish duo Maciej Chmara and Ania Rosinke moved to Austria as students, stayed “by coincidence” and have made their home in Vienna. But their work, with its sense of community and DIY aesthetic, explores the restlessness, impermanence and inhospitability of life in modern cities The workshop of Polish-born, Vienna-based design duo Ania Rosinke and Maciej Chmara (together, Chmara.Rosinke) overflows with prototype objects and experiments-in-progress. The space is part graveyard for the disassembled remains of projects past, part laboratory for future creations. Lined with lengths of wood – some formed into grid-like wooden shelves, others propped around the exterior – it nods to the DIY ideals at the heart of many of the pair’s designs. The geometric bases of a circular table shown in Milan surround industrial machinery while, on a worktop nearby, off-the-peg components made from copper and brass sit next to natural sponge segments and splattered moulds. The latter belong to a series of vases developed for an exhibition at Sotheby’s Vienna, part of the Austrian capital’s Design Week last year. We’ve just made the ten-minute walk from the couple’s apartment with their three-month-old twin sons in tow, and the contrast is staggering. The flat was formerly the home of one of Austria’s most famous modernist designers, Carl Auböck (Chmara tells me with delight that Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius was once a visitor). Its high ceilings and white walls are a calm backdrop for their own pieces (a cubic sofa they made after they couldn’t find one they wanted and a spider-like brass chandelier that’s a redevelopment of Lindsey Adelman’s You Make It lamp) and a few classics that hint at their ideological interests – a chair by the Memphis Group’s Michele de Lucchi, for example. But it’s in the chaos of the workshop that the pair seem most excited: Chmara whizzes around the space explaining how they achieved a sheen on the concrete vase base for Sotheby’s by adding a top layer of water during the moulding process, while Rosinke chimes in proffering half-formed shapes made from an alloy called alpaca silver that are soon to become a cutlery set developed as part of their Nespresso Design Scholarship.

2,53, the duo’s “living cube”

Sponge and concrete vases for an exhibition at Sotheby’s in Vienna Whether small-scale objects like a portable cooking set that won them the Prix Émile Hermès last year, or larger installations such as their re-imagining of Victor Papanek and James Hennessey’s “living cube” (a modular micro-house complete with bed and kitchen), the concepts behind Chmara.Rosinke’s projects often stem from a desire to change how people live and interact. The cube, called 2,5³, was developed for an exhibition at Arsenal gallery in Poznan in 2013, and slims down Papanek and Hennessey’s vision even further with the help of contemporary technology. Designing for a generation constantly on the move is a core interest for the pair, as is encouraging people to think more responsibly about consumption and public space. “We’re not like the postwar society, who only thought about earning money,” says Chmara. “We study for longer, we choose our jobs more consciously, we try to be happy. If you can live with less and your aim isn’t to be rich, you start becoming interested in other things – like food or design.” Chmara and Rosinke have worked together since their studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in Gdansk, the Polish coastal city where both designers were born. After their first year, they applied for a scholarship to the Space & Design Strategies programme at the Kunstuniversität in Linz, Austria – the pair were keen to explore the design world outside of Poland. “We were a new couple at the time,” explains Rosinke, “and there was only space for one student at Linz, so we had our portfolios bound into one book and asked whether we could come together … as one person!” Later, a tutor at Linz suggested the pair to a contact as possible assistants for a book being compiled in Vienna, so they moved to the city for eight months, commuting back to Gdansk every three weeks to consult with their professors. They still live in the city six years later – “We kind of stayed here by coincidence,” Rosinke admits.

The couple’s home in Vienna’s 7th district, which is still owned by the family of Carl Auböck

A chair by Michele de Lucchi sits in front of homemade shelves

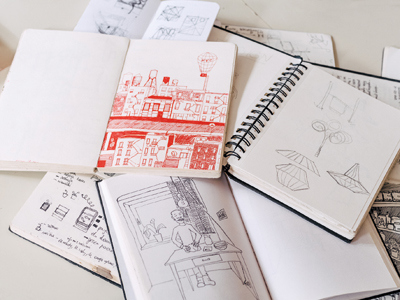

Sketches for Mobile Hospitality As outsiders, Chmara and Rosinke initially didn’t have the contacts to win local commissions, so worked on self-initiated projects while also holding down jobs at architectural practices to make ends meet, something Chmara found frustrating. “I’m kind of nervous when it comes to projects and I like to finish things,” he says. “Architectural projects can go on for years. As a designer with a workshop, you always have the opportunity to go into your studio and take a piece of wood or steel and prototype something or create a piece with the 3D printer. Design gives you more satisfaction because you get a bigger output.” Space, especially the public realm, has remained important for the designers. Mobile Hospitality (2011) is a wheelbarrow-like wooden structure, complete with a gas-cylinder stove, footpump-powered sink and utensils rack. It works as a portable outdoor kitchen but was designed to bring people together to get to know each other and talk about the design of their city. Developed as part of Austrian festival ArtDesign Feldkirch, the project initially took place in public squares in small Austrian cities such as Dornbirn, Bregenz and Feldkirch, but has since toured around the world, most recently New York last May.

Tableware made as part of a collaborative project with chef Konstantin Filippou

Developing a kitchen was purely a pragmatic move: the pair realised they needed to provide food and drink to keep visitors interacting. “People initially thought they were being tricked in some way, or that it was an advertisement, because the market has got us all used to that,” says Rosinke. “But when they understood the project, you could see the idea click. Time is so valuable at the moment that spending it unplanned with strangers is unheard of.” Having designed the kitchen functionally, with dimensions dictated by the size of a Euro-pallet, the pair were surprised when the piece itself started winning design prizes. “Our objects seem to have the biggest success when we don’t think about them as objects, but rather as fulfilling some kind of need. You think a lot more freely and not so much in the stereotypes of existing forms.” Mobile Hospitality also had a spatial imperative – to encourage a responsibility for public space, which, the pair point out, often ends at the front garden. “Some people changed their view of the city and didn’t just see it as a kind of scenography for a Sunday walk,” says Chmara. “They could now see that the space had potential – potential for being used actively, for having fun.”

Prototypes, material experiments and industrial machinery fill the duo’s workshop

Much of the duo’s carpentry skills were self-taught while studying in Linz

Chmara.Rosinke’s vertical kitchen (adapted from a 1941 design by Ferdinand Kramer) was developed as part of their MAK residency The portable unit created for Mobile Hospitality has spawned several other iterations. In 2013, clothes retailer Cos commissioned Chmara.Rosinke to develop a portable pop-up shop to showcase its new collection, which used the wheelbarrow concept, albeit with a thinner frame to create a sleeker silhouette. For Vienna Design Week the same year, the duo built a portable dressing room to celebrate the craftsmanship of tailor Wäscheflott (a project that sits somewhere between the Cos pop-up and 2,5³) and in 2014 they were asked to develop a more permanent modular kitchen for a cafe in Vienna’s Ankerbrotfabrik. Run by charity Caritas in co-operation with the Jamie Oliver Foundation, the pilot aims to educate communities about the value of food through cooking together. Cooking rituals also feature in their next project for the Nespresso scholarship, which involves working with chefs to design tableware inspired by their recipes (and vice versa) in a culinary game of Consequences. Unlike their native Poland, Austria has a small manufacturing industry (with a large percentage of its designers working in transport infrastructure) – something which Chmara and Rosinke say acted as a catalyst for their trajectory. “You’re forced very fast to do something alternative in the design scene here, or go into the luxury craft sector,” explains Chmara. Since the duo moved to the city six years ago, they feel that the design community in the capital has changed rapidly. Vienna Design Week launched a year before their arrival, while the appointment of curator Thomas Geisler to MAK, the city’s design museum, signalled a greater interest in involving younger, more experimental practices at the institution.

Vases in progress for the Sotheby’s collection

The Make It Yourself Europe light hangs above a homemade sofa In 2013, following Geisler’s invitation, Chmara and Rosinke undertook a year-long residency at MAK, tasked with re-evaluating what you might call the “classics” of DIY design, which resulted in the exhibition Nomadic Furniture 3.0. They worked through more than 120 manuals, from 1850 on, including publications released by the Nazi Chmara and Rosinke also reinterpreted some of their favourite designs themselves for the show: a nomadic ironing table, a vertical kitchen (adapted from a 1941 design by Ferdinand Kramer) and a table with an inbuilt record player from Papanek and Hennessy’s iconic DIY book Nomadic Furniture 2.0, from which the exhibition name comes. As well as ironing out the considerable mistakes they found in the original plans, the duo were keen to make the pieces increasingly modular and portable. “We don’t like [the idea of] looking through an Ikea catalogue and choosing something that’s OK because you can afford

The Time for Oneself cooking set developed for Hermès

The portable kitchen developed as part of Mobile Hospitality

The Miron chair, developed in 2008 “When people were building their pieces at the MAK, at the beginning they said they wouldn’t take them home, but by the end nearly everyone wanted to,” says Chmara. “They were proud of their achievements and emotionally connected.” The duo have taken this on board with their own products; their You Make It Europe lamp (2013) can be bought direct or, for half the price, you can make it alongside Chmara and Rosinke in a special workshop. “We wanted to teach people that things are not as difficult – or magical – as they look. You often forget that many mass-produced products are actually made by hand, just by cheap labour,” adds Chmara. Considering their location in Vienna happened almost by chance, they’re now firmly rooted in the city. Before the twins arrived, they mooted the idea of setting up a sister studio in Warsaw, but their next venture – a design gallery they’re starting with fellow Viennese studios BreadedEscalope and Patrick Rampelotto – signals a more long-term commitment to the city. Launching in September as part of Vienna Design Week, the gallery will be a home for the many material experiments, soon-to-be-completed prototypes and investigative side projects now scattered across Chmara and Rosinke’s jam-packed workshop. “We’re all very different studios so I’m not sure what the outcome will be,” says Chmara. “Perhaps we’ll develop a style, as the Memphis Group did. Perhaps it won’t work and we’ll close the gallery in half a year – it’s an exciting experiment!” |

Words Laura Snoad

Photography Klaus Pichler

Above: Chmara and Rosinke with the base of a table shown in Milan |

|

|

||

|

The portable kitchen in use |

||