|

|

||

|

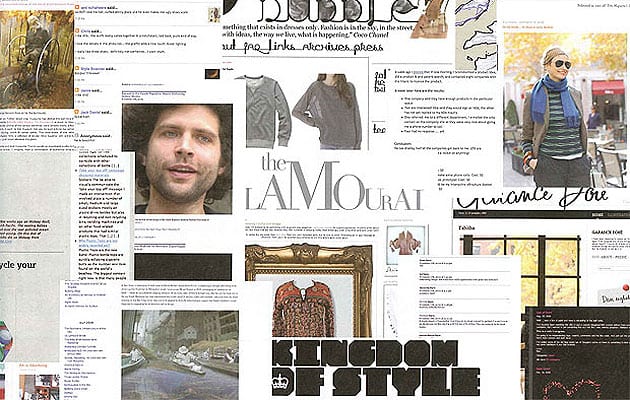

The web passed two milestones in the past few months. Firstly, the blog-hosting service Blogger.com celebrated its tenth birthday. Secondly, Yahoo’s geriatric web-page creation service Geocities ceased operating, snuffing out a thousand animated “under construction” logos. Those dancing little “under construction” images – swinging cranes, flashing hazard lights, toiling stickmen – now look absurdly dated, and the fact they do tells us something about why Geocities failed, why Blogger (and similar services) succeeded, and how the web works. Geocities was, in its time – it started in 1995 – a pioneer. Pages on Geocities might have been a byword for amateurish and ugly, but they gave a wave of web users their first experience of content creation and helped establish the web’s bottom-up ethos. But it spawned those blinking “under construction” logos because web pages were still seen as being something to be finished. Geocities users, embarrassed at pages left “incomplete”, would put in the flashing hazard lights and warning signs to say they would be back later to finish the job. Of course, many never did, and the place was a graveyard of aborted sites. Blogging, and Blogger.com, changed that. Blogs – if there is anyone left on the planet who doesn’t know this – are diary-format websites. They do not treat websites as discrete objects to be completed, but as dynamic, ever-changing entities – living, growing organisms. Websites matching the blog format can be found in the earliest days of the web, but the word “weblog” was coined in 1997. Blogger was set up in August 1999 by San Francisco-based software company Pyra Labs. Any website with an address ending .blogspot.com is a Blogger blog, and there are plenty of others besides. Blogger was hugely successful at popularising the blog form, and it broke new ground in ease of use. If Geocities made setting up a website fairly easy, Blogger made it near-effortless. Once a user had filled in their details, given their blog a name and picked a design template for it, they were ready to start writing posts and putting them online. This was a great democratisation of web design, and was rewarded by a stunning burst of success. Although it was already popular, blogging took off spectacularly in the wake of the collapse of the first dot-com boom. In 2003, Blogger was bought by search giant Google, recognition that it had entered the internet mainstream. Blogs have also since become part of the broader design and architecture mainstream. Sites like Designboom, Dezeen and Design Observer all run along blog lines and have changed design discourse forever. But those professional hubs are matched by hundreds, even thousands of so-called “amateur” design blogs, many of which are run on Blogger and give the established media serious competition in their relevance and intelligence. At the other end of the spectrum, this new world can be a dispiriting place. One of the advantages of blogs is that they encourage dialogue with their readers – the trouble is that in many places an endless procession of shiny renderings is given one-word assessments (“Cool!” “Crap!”) by a peanut gallery of anonymous commenters. Design is reduced to a beauty contest judged by hecklers. The end of the traditional media’s monopoly on comment has been a leap forward for democracy, but there was something to be said for the pruning hands of editors. Ultimately, however, a bit of crassness is a small price to pay for such an extraordinary communication tool. |

Words William Wiles |

|

|

||