|

Icon went to Berlin for the DMY design festival. Over the course of 48 hectic hours of shows, talks and parties, we took the temperature of this fledgling fair and interviewed five designers who call the German capital home. The restless energy of the Berlin design scene echoes through the city’s strange abundance of empty space. The city is heaving with deserted factories and offices – which is exactly why it’s such an appealing destination for designers to set up shop. Maybe it’s that start-up atmosphere that gives DMY the feel of a design festival for beginners. After seven years it’s still finding its feet and feels like a chill-out after the well-established Salone in Milan and ICFF in New York. “We’re at an in-between stage,” explains DMY’s director Jörg Sauermann over the booming music when I meet him at the DMY Youngsters exhibition. “We’re in between being a creative platform and being a commercial event.” This year DMY has tried to lure some big names to the city with a new exhibition called All Stars, but the most interesting work was still to be found among the new practices and recent graduates showing at DMY Youngsters. Much of the work, such as Eindhoven graduates Trixler & Machler’s inventive solar-powered furniture machine, was familiar from either Milan or Cologne. But a good deal was new, such as the ultra-minimal furniture and tableware of Tomoshi Nagano and Shinsaku Fukutaka, two Japanese designers living in Finland. But this year the real strength of DMY was as a platform for discussions around design, something there is little time for in Stockholm, Cologne or Milan. The speakers at the DMY Symposium, which included Jurgen Bey, Arik Levy and Marije Vogelzang, were more impressive than the exhibitors at All Stars, and Chris Bangle gave a barnstorming performance at a Youngsters event. The constantly transforming fabric of Berlin makes it an ideal place for interesting happenings, and this year these fringe events were united under the name DMY Extended. The most impressive was Einfach, or Simplicity, organised by Designmai, which looked at the design of everyday objects. But it was in the studios of the designers we visited, from the conceptual designer/researcher Judith Seng to the die-hard industrial designers Studio Hausen, that we got a real sense of the city, as you can can read over the following pages.

Läufer & Keichel’s chair made from fruit boxes

Transalpino’s designs from wood veneer

Martin Meier’s ode to the Lamborghini Countach at Appel Design Gallery Judith Seng Judith Seng doesn’t mind mess – in her work or her cluttered Mitte studio. Ever since she graduated from the Berlin University of the Arts in 2001, she has been investigating concepts of perfection and imperfection while establishing a reputation as one of Germany’s most intriguing designers. Her best-known project to date is the limited-edition Hide and Show wardrobes. They only partially conceal the clothes, making the user more conscious of what it is they actually have to hide. But when we meet in her new studio the only piece of her design on display is the Patches table. Patches is four small tables, each with a different surface, that can be moved and reconfigure as needed. It’s an informal composition – as Seng says: “I’m not so interested in form-giving.” She continues: “For this project I was more interested in the changing idea of eating together.” It’s an example of how she sees design, as “the practice of rethinking daily life”. Seng enjoys observing how people interact with the things that surround them, a sideline in anthropological research that has always informed her design and is now becoming a business in its own right, with clients ranging from universities to car manufacturers.

Osko & Deichmann Like many Berlin designers, Oliver Deichmann and Blasius Osko met at the Berlin University of Arts, where they studied industrial design. They set up their studio in 1998 while still students. “When we came to Berlin in the mid 1990s there were islands of things going on but the design community wasn’t that strong,” says Deichmann. “A lot has happened since then.” One big difference is the arrival of design galleries, and it is in one of these that Osko & Deichmann is presenting its latest work during DMY: Straw, a limited-edition cantilever chair made from kinked tubular steel. The Straw chair is built by hand in Osko & Deichmann’s studio. The steel is kinked into the shape of a chair and then nickel-coated before a leather seat and back are added. “We were playing around with different processes of how to bend the steel,” says Blasius Osko. “To kink it seemed so simple and yet so effective.” The Straw project represents a new departure for the studio, which has so far produced such pieces as the Clip chair for Moooi, the Ponton table for Ligne Roset and the Pebble sofa and chair for Blå Station. But Straw has whetted their appetite for more limited-edition work and they are currently developing it into a series. “We’re going to Basel for Design Miami to meet with a few galleries next week,” says Deichmann.

Happy Birthday Bauhaus at Contributed, Studio for the Arts, 2009

Blasius Osko and Oliver Deichmann

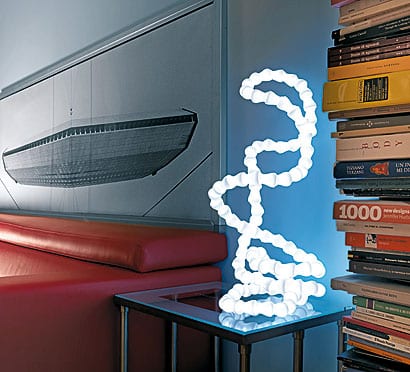

Abyss light for Kundalini, 2006 Studio Hausen Jörg Höltje only graduated from the University of the Arts in Berlin in April – and Joscha Brose won’t be out until October. But already the pair, under the name Studio Hausen, have the Serpentine lamp in production with Ligne Roset and the Ringer lounge chair in development with De La Espada. They set up Studio Hausen in the autumn of 2006 and presented the studio’s first work at Salone Satellite in 2007 to see how it would go down. “It was a bit of a creative explosion,” says Höltje. “We showed 11 projects and people wouldn’t believe it was just the two of us.” There is a distinct look to Studio Hausen’s pieces. They’re pared down and often borrow from industry, adding a very functional aesthetic to the design. For example the Crooner LED light is inspired by the cooling elements in machinery, and there’s a good reason for that. The high-powered LEDs used in the lights produce a lot of heat and the shape and thickness of these heavy cast-aluminium shades makes them easier to handle. Here the function is entirely concealed in the appealing form. The latest projects from Berlin’s young guns are their individual diploma projects. Brose’s is still at a research stage and blobs of foam are scattered all over the studio. Höltje’s is just completed. It’s an ultralithe hydroformed stainless steel chair called Hydra. Because of their busy diploma schedules, Studio Hausen didn’t present at the DMY festival this year. Instead they are planning a big comeback in Milan in 2010, part of a group show with other Berlin-based designers. “We are original Berliners and are interested in how the city has developed as a design city,” says Höltje. “It is definitely the right time to start a studio here,” says Brose.

Crooner LED light, 2008

Serpentine lamp, Ligne Roset, 2008

Joscha Brose, left and Jörg Höltje, right Mark Braun Mark Braun’s Lingor pendant lamps in phosphorescent enameled steel were among our favourite things at last year’s Milan furniture fair. This year the cluster of lamps has found a producer in German manufacturer Authentics. “I have just offered them my help in developing the first prototype,” says Braun. “I know how important it is that they are happy with the first piece or else they might stop the whole production.” Braun is a craftsman with an appetite for mass production. He studied at the University of Applied Sciences in Potsdam and graduated in 2006, but before that he trained as a carpenter. His Berlin studio is dominated by a workshop where he makes all his pieces and making is central to his design process. “In the practice of making things I see how I can develop the process,” says Braun. In all his projects, Braun expresses a sensitivity towards material. His work is characterised by unexpected touches, such as the glow from the Lingor lights once they are switched off, or the velvety feel of his Fusion porcelain collection. His latest piece, Pyrus, also a light, is made by pressing paper pulp into a mould and letting it dry. Although it seems ideal for limited-edition production, Braun has no interest in that and has already made contact with a company with the know-how to produce them.

Pyrus light, 2009; Kluwen sitting ball for Raumsgestalt, 2004 Mashallah “We would like to fuse fashion and product design,” says Murat Kocygit of Mashallah Design. He met Hande Akcayli when they were both students at the University of the Arts, Murat as an industrial designer and Hande as a fashion designer. These interests came together for the Diva project – wallpaper with a fringe along the bottom. Subsequent projects similarly play with the idea of turning something 2D into 3D. For the Superfax project, which they showed in Milan earlier this year, they faxed a pattern to a ceramicist in Barcelona who then made ceramic lights for them. Mashallah’s studio is littered with folded paper patterns, part of the T-Shirt Issue, their current project – which they showed at the London Design Festival last September, that they are now developing further. In collaboration with fashion designer Linda Kostowski, they create T-shirts that resemble origami. Together they are looking to push the production method of garments by looking to other industries, like car seat manufacturing and developments in rapid prototyping, for inspiration. “There is such strong development in rapid prototyping machines at the moment and it makes no sense that they stop in front of textiles,” says Kostowski.

Linda Kostowski, left, Murat Kocygit, middle and Hande Akcayli, right, with the first prototype of the T-shirt issue in the foreground

The Superfax project, 2009 |

Portrait Thorsten Klapsch

Words Johanna Agerman |

|

|