|

Artist’s impression of Industrial Facility’s portable projector for Epson |

||

|

“There’s a saying in our trade: the better the idea, the more unlikely it will see the light of day,” says Sam Hecht, partner of design studio Industrial Facility. For every design that manages to pass the many hurdles of evolution, testing and approval and finally make it out into the world, there are scores of products that didn’t get that far. Designers do a vast amount of work that never materialises and, like fishermen, they can be at their most wistful talking about the “ones that got away” – the brilliant product for the household brand that was thwarted at the last minute. But if it didn’t make it, it can’t have been all that brilliant, right? Sometimes, but not always. The things that don’t get made tell you almost as much about the way the design world works as the things that do get made. A design can be killed by risk aversion, infighting, corporate intrigue, refusal to experiment, sudden shifts in the market, business failure or – in the case of at least one product here – the mystifying failure of one branch of a business to talk to another. Sometimes – surprisingly often – the axe falls at the very last moment, when thousands of units of a product have already been made. And sometimes the company never intends to make the product – it just uses the prototype, which the designer developed for nothing, to add a bit of glamour to its collection and generate press interest. What we have gathered here is a glimpse into this fascinating parallel universe of design – the things we could be living with now, but aren’t. It’s only a tiny glimpse, the tip of the iceberg. We can tell you that there are hundreds of products out there, ready to go but hidden, a lost world of stuff like the mysterious warehouse seen at the end of Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark. So why can’t we show you more? Believe us, we tried. But this parallel universe is surrounded by an extraordinary culture of secrecy. Time and again, we asked to show products we knew existed (wouldn’t you like to see Ettore Sottsass’ tablet computer for Apple?), and were met with a flat refusal. Sometimes, this emanates from the companies that commission and then quash the designs. A picture of Industrial Facility’s cancelled portable projector for Epson – imagine a Muji CD player that shows movies – used to appear on the studio’s website. It attracted a continuous stream of queries from people wanting to buy it. You’d think that would please Epson, but instead the corporation asked for the picture to be taken down. The reasoning behind decisions like this is generally inscrutable – no doubt companies feel their omni-confident mystique is threatened by showing their rejects. Sometimes, though, it’s the designers who don’t want to show their nearly-stuff. These ideas are like a creative bank account for designers. They still have high hopes for these products, which can be recycled for other clients. To publish unrealised work is to let go of an idea and run the risk of another designer picking it up. All they have to do is change the shape or a detail and take it to another manufacturer. The hidden parallel universe is a storehouse of treasure – it’s fascinating just to peer around the door. Yves Béhar It has a little button at the top, and you have to squeeze the sides at the same time. The function is to activate two things at the same time, but it’s quite easy to do it in the palm of your hand. The bottle opens, and then when you turn it around, it’s more of a spout, dispensing one or two pills at a time rather than a whole lot flooding out all at once. Why didn’t it make it? Tylenol is a very, very large brand – you’re talking about millions of pills being made every day. To change from the existing containers to the new ones requires building new facilities, and building very expensive tools and systems. In the end, even though everyone wanted this project to happen, and everyone was aware of the cost, and we kept in line with the manufacturing costs that the company expected, it was one of the big projects that year that needed funding and just didn’t make it. It was unfortunate, but the interesting thing is that Tylenol was still very proud of the work and told us that we could show this in a MOMA exhibition, Safe. And I don’t think it’s entirely dead yet – it just hit a funding glitch.”

Inga Sempé The prototype was made from pressed glass in a wooden mould, then it was metallised on the upper part. The point is that there is a mechanism that shields the bulb and the light shows through either at the top of the shade or the bottom through the glass, depending on what position you put the dial in. It’s very difficult to produce a huge piece of glass with a metallised section like this one has, so it couldn’t quite fit the aim of perfection that we are used to in industrial production. Finally, Luceplan only showed one more project that year, while Artemide and Flos showed over 20 new lamps.”

5.5 Designers The only problem was that 45,000 units had already been made – about nine large truckloads. Then we received a letter a year later asking us to consult them on the destruction of the entire range. It came as a huge surprise. We then realised that they couldn’t destroy it without our permission so we started negotiating to take the stock instead. Now we call the project Save a Product instead, and we travel to design fairs around the world selling the wares for €1 apiece. In fact we did our last sale in Toulouse last week but we still have a few pieces left. The main point of the project is not the product but the story. It’s funny because now the French state design collection – the Fonds national d’art contemporain (Fnac) – has bought a set too, so something that was about to be destroyed is part of a permanent design collection.”

Sebastian Bergne The glass itself is bubbly so that it has a relationship to the content. I think the samples were made in Eastern Europe or maybe even India, but Driade was not happy with the quality of the glass. It was made up of a lot of small bubbles that made the glass look frosty. Because we didn’t have direct insight into this process, the project was delayed and then it was too late to produce anything in time for the New Year’s Eve party. At the time I was slightly pissed off, I just wanted to make them. But the number of products that never make it into production is huge. You go through so much work to get a product made and then for really stupid and really small reasons it doesn’t happen, but you get resilient. I managed to get these two prototypes of the glasses and I use them at home with my wife sometimes. As far as I know they are the only two in existence.”

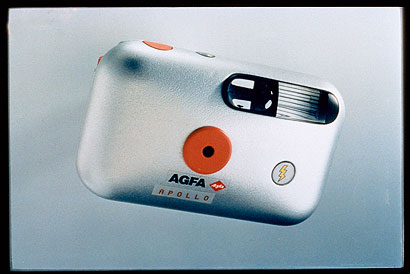

Sottsass Associati They had a competition with some leading design studios, like Porsche Design and I think one was Frog Design. The brief was to make the disposable camera more interesting – more artful, more enjoyable. I worked with Ettore [Sottsass] on it and we were saying that the biggest problem with cameras was that they were all rectangular black boxes. Our idea was to do it like a bar of soap so it slipped into your pocket or your bag much more easily – to do away with all these hard edges and make it more ergonomic, personable, softer. That’s the genesis of the idea. In 1998 it was radical. We went to present it to Agfa in Leverkusen and as soon as we pulled it out, their jaws dropped. I had only come for the day but they changed my flight because they wanted to talk about it even more. The next week they sent us an official letter saying they had decided to go for the proposal. They were even planning to construct a new factory especially for this camera. For me it was really weird that this big company was moving so quickly on this project. Then one day, we just got this letter saying, ‘Due to circumstances with our mother company, Bayer …’ Basically Bayer had decided to either sell Agfa or pull out of it, I can’t remember, so the project was abandoned, and from that point on Agfa just nosedived and disappeared almost. That was the start of the digital revolution. Their marketing people had made the wrong decision. In fact, I remember being at the meeting and saying to them, ‘Don’t you think it’s much more innovative to do a digital camera in this form rather than a film camera because film cameras aren’t the future.’ We were trying to persuade them to move forward rather than move backwards, I remember that quite vividly.”

Jerszy Seymour Let’s call it an anomaly of the modern world. It was a special request from them with a specific price point and market in mind, so in a sense changing their mind about it was a turnaround on their marketing decision. I designed it, we did the consumer test and it passed that. We did the safety testing and it passed that too and at this point it was getting expensive. Then the moulds were made and the packaging was designed. I don’t know how many were actually produced in the end but at least a few thousand. And it was at this point that Moulinex turned around and said that they don’t do bodycare products and so it was scrapped. I keep about 50 here in the studio and I give them away as gifts sometimes. I’m not really sad that it’s not in the shops. Of course I would have liked it to be, but for me the success of the project was to finish it. It is mass production at its fullest, so every decision you make is carefully scrutinised and every €0.001 makes a difference. It’s an important education for every designer, whether they want to work with it or against it. You can call it my educational project.”

Boym partners At the time we were doing two stores for Vitra, one in Chicago and one in New York, and we started to get to know Rolf Fehlbaum quite well. And he was interested in the chair, but at that time there was no Vitra Home and the company’s focus was on office furniture. However, he decided to develop a prototype and we opted for a tubular steel frame instead of the wood. But there was a problem with the strapping and they sent the prototype to us to work on that, but at this point the project stalled and they didn’t take it forward and nor did we – and then the momentum was gone. We kept the prototype here for a while, but in one of our many office moves I looked at the thing and said, you know what? I think this should go. So even the prototype doesn’t exist anymore. I told Rolf off about this afterwards, that he shouldn’t have given up, because right now it would have fitted in very well with their collection. But there is something beautiful about unrealised projects, about projects that aren’t yet limited by the constraints of industrial production.”

Front On the morning of the exhibition opening at the fair they came and took away our prototype. That was the power this designer had, and we just had to more or less agree on that because we couldn’t fight it. She had already collaborated with them and was in their collection already, and we weren’t. Of course we tried to make the point – who owns an idea that is hidden in someone else’s desk drawer? It was a big disappointment at the time because that was one of the first pieces we had that was going to be professionally produced. We didn’t have that many products that were in actual production. It was a big drama at the time. It’s interesting how people can claim somebody else’s idea. But it was definitely nothing that she had that already existed or had been shown anywhere else. It was just more or less in her head. Anyway, we’re working on a variation of that idea now for Porro. We’re changing it to make it different – it’s a different manufacturer – because it feels like you can always improve an idea and work with it further. It’s still not definitely going to happen though.” |

|

Words The Icon Team |

|

||