|

When Football Hooligans Become Hindu Gods |

||

|

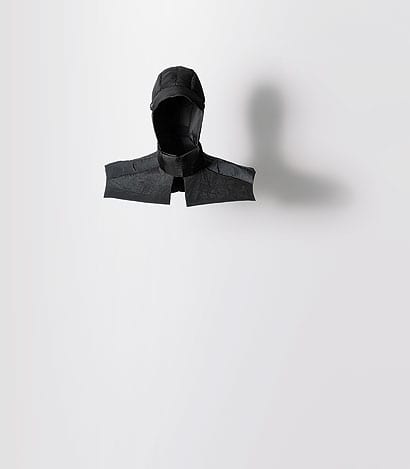

Thanks to Aitor Throup the England football team may have a psychological edge. The 29-year-old recently designed the national team’s impeccable new kit, and he’s waiting to see if his tailoring affects their performance. Throup is Britain’s most interesting young menswear designer. Deeply uneasy about the fashion industry, his work can best be described as conceptual, but his skills, honed at the Royal College of Art, are not used for haute couture creations. Instead he tailors unique garments for the streets and now the football pitch. Throup is to fashion what Banksy is to the art world. His studio is in Seven Sisters, a pocket of north London that hasn’t yet been touched by gentrification. It is on a street of largely abandoned office blocks inhabited by squatters, dry-cleaning depots and big posters for adult education schemes. “Tottenham is the future, everyone is going to be living here,” teases Throup. “When it becomes like that, crappy and trendy, we’re going to move out.” There are three people working in the studio today, but the number changes depending on workload. Right now it’s a quiet period. Throup isn’t showing at London Fashion Week, which is just about to start when we meet, and his latest project, a redesign of the iconic Goggle jacket for Italian label CP Company, is done and is now going into stores. The studio is lined with the amputated limbs of home-made dummies, but otherwise it’s in perfect order, as if the maid has just been. Throup speaks with a thick Burnley accent that conceals his multicultural past. He was born in Buenos Aires, grew up in Madrid and came to the small town in northern England at the age of 12. His name perfectly reflects that northward trajectory – Aitor is an old Basque name, while Throup has Scandinavian roots. He assimilated well, it seems – all his cultural reference points are English, from football to music – and even if he still speaks fluent Spanish it’s difficult to imagine him making the transition from northerner to Latino. He is so ridiculously well-spoken that I wonder if there is an autocue somewhere behind me. The “you knows” and “kind ofs” that normally litter an interview are absent. It feels like Throup is performing the role of the creative and every time I ask a question I’m interrupting a carefully rehearsed act. Throup has designed only two collections since his graduation from the RCA three years ago. When Football Hooligans Become Hindu Gods was his first, unveiled in 2006. It was a feat of tailoring and an ode to his northern past. “My original inspiration came from watching football and being surrounded by some very violent men,” says Throup. “Not that everyone who watches football is like that but in Burnley you see a lot of it, and what really inspired me was that a lot of these guys would be wearing this beautiful product – it was like fancy dress in a creatively recessive environment.” The collection is built up around a story that Throup invented about a group of hooligans that beat a Hindu boy to death. In an attempt to make good and honour the boy’s beliefs, the hooligans restyle themselves as Hindu gods. Each piece in the collection is an exact copy of a military garment and each garment morphs into a depiction of a god. The elephant head of Ganesh has been unzipped and forms the hood and neckpiece of a jacket; Shiva’s destructive qualities are represented by several skulls hanging menacingly from the shoulders of another. The trousers have “feet”, the jackets “hands” because Throup hates the idea of a garment finishing at the ankle or wrist. In his clothes, he builds in a solution to the urge we all have to pull a sleeve over our hand, or adjust the waist of our trousers so that the leg falls at the right length. Throup calls it branding through construction.

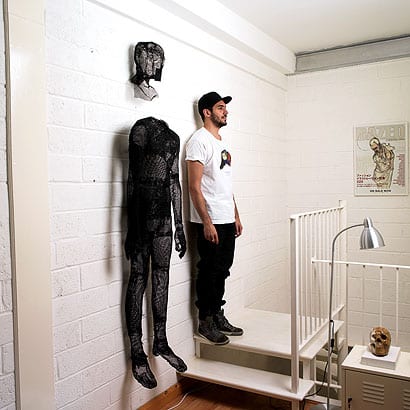

Aitor Throup with a mesh mannequin Every detail in Throup’s work has to be justified. “I hate the idea of just sitting there with a blank piece of paper and deciding what looks cool, where should I put a seam and what colour should I make it,” says Throup. “I’m afraid of that process. I’m really insecure creatively in that sense so I always have to give a reason behind everything so that people can’t question it. Or they can question it but I can answer it.” This is why his collections become stories, beautifully retold through Throup’s sinuous drawings, but his illustrations aren’t what we normally encounter in fashion. His characters are picked from the streets of northern England, and they are hunched over, pot-bellied, angry, red-nosed and shivering. He then builds 3D models from the drawings – the studio is full of the life-size mesh and duct-tape figures and miniature models of torsos that Throup works on. He pins the fabric to the figure in the shape of the garment and creates the pattern from this. It’s a laborious process and it means that every new thing that Throup creates, from elephant heads to football shirts, exists as a 3D model before it becomes a garment. Throup sculpts rather than constructs clothes. “I never believed in the creative limitations of the fashion industry,” says Throup. He’s not interested in fitting his exhausting creative process into the industry’s six-month cycles. Instead he works at his own pace. Since his last collection, the equally evocative The Funeral of New Orleans in 2007, most of his time has been dedicated to building jackets for two of his favourite labels, Italian CP Company and its subsidiary Stone Island. Both are known as the labels of choice for England’s football-supporting subcultures, or casuals, a culture that Throup has known since his teenage years. One of these jackets, Modular Anatomy for Stone Island, has such complicated construction that it is regarded more as design engineering than fashion design. Each pocket is individually sewn into a perfectly tailored patchwork to create a puffy whole. The latest instalment of the series, premiered at the Milan furniture fair last April, is the outcome of an anatomical exploration into how the range of movements influence the stretch and fit of the fabric, making room for more movement and comfort. Throughout his education, Throup fought against formulaic fashion design, and this now drives his creative process. The jacket forms an important part of Throup’s work and its silhouette has preoccupied him since his teenage years. The jacket or the hoodie is integral to youth cultures – it inflates the volume of the body and conceals insecurities. In Throup’s garments this psychology is easy to grasp. His pieces present the 21st-century male as a vulnerable species who wears his garments as a type of armour against the world.

Mesh mannequins in Throup’s studio His curiosity about the psychology and the performance involved in male dressing was the starting point for the English football kit that he has developed with Umbro, a case of building style into performance. The all-white kit is a study in minimalism but there is nothing simple about it. Here Throup’s innovative tailoring skills and obsession with anatomy has been pushed to their limits. “I just loved the idea of making football kits that actually look good, not just crap and shiny with bits of meaningless colour,” says Throup. The kit is tailored to each individual player and its monochrome surface conceals its innovative high-tech materials. “The articulation of the new construction in this particular piece is hidden in the underarm and I love the fact that we can create this innovation and put it here,” muses Throup. “The fact that they look smart and so different from their opposition, so sleek, the psychological implications of that are very interesting to me. It’s hard to go out there and play sloppy.” The pinnacle of the research process will be next summer when the World Cup kicks off in Johannesburg. Despite his success as a consultant for football’s biggest labels, both on and off the pitch, Throup sees himself as an independent designer first and foremost. He is now working on his third collection, due to show in January 2010, and is in talks with several galleries about showing it in an art context rather than as a fashion show. This artwork will form the foundation of a “library of ideas” for future collections; instead of reinventing himself every season, he will use this library as a starting point, producing the same style of trousers or jackets but in a new fabric or colour. “The Japanese fashion system, which has an intriguing link to continuity and product, not just fashion, got me to think of this idea of having a product line that sits somewhere between avant-garde, niche fashion and sculptural work and a very strict, continuous product line,” he says. It seems that Throup has found a way of breaking free from the restrictions that he feels the fashion industry is imposing on him. “It doesn’t make sense if you are creating something truly new for that to have a timeline of only six months.”

The Google jacket for CP Company

“Shiva” from When Football Hooligans Become Hindu Gods

The England football kit for Umbro, individually tailored to each player

The process of creating a garment always starts with 3D modelling, from which Throup makes the pattern. This is the Modular Anatomy jacket for Stone Island, 2008

The process of creating a garment always starts with 3D modelling, from which Throup makes the pattern. This is the Modular Anatomy jacket for Stone Island, 2008

The process of creating a garment always starts with 3D modelling, from which Throup makes the pattern. This is the Modular Anatomy jacket for Stone Island, 2008 |

Image Steve Double

Words Johanna Agerman |

|

|

||

|

The process of creating a garment always starts with 3D modelling, from which Throup makes the pattern. This is the Modular Anatomy jacket for Stone Island, 2008 |

||