|

|

||

|

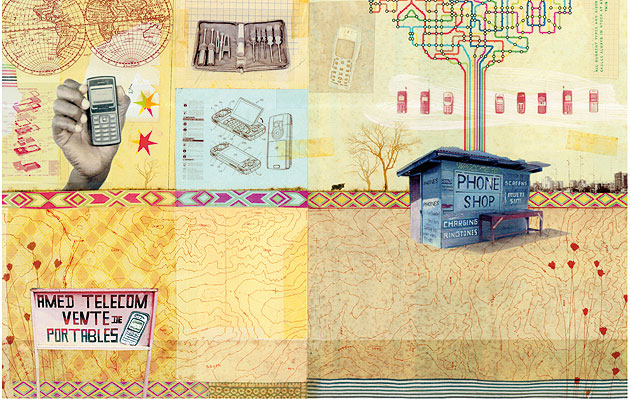

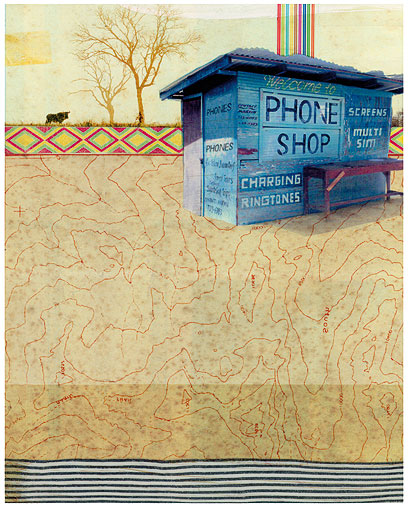

Think your smart phone is cutting-edge? The real innovation is coming out of Africa’s mobile culture, says Jan Chipchase Go into Any large city in africa and there will be one part of the town where the buyers and sellers of mobile phones are concentrated, in the same way that you get restaurants or shoe shops clustered in the same area. Many of these phones are second-hand – a few hundred thousand phones are discarded every day in America and Europe, and if they still have value many of them end up in other countries. Some are shipped through formal channels, but many are carried by people returning home with old phones that have been sitting in the back of cupboards. In any cluster of mobile phone shops you find someone who offers repair services. This typically starts out as people fixing displays and speakers, which tend to break first. People then come asking if other things can be fixed, and over time there’s an increased awareness of how to fix different models. Nokia tends to be the dominant player in those markets, so people tend to know how to fix them, right down to soldering bits of the circuit board. It’s from those repair services that a street-hacker culture originates. People make a bit of money repairing stuff so it can live longer and then figure out other services they can offer. So a guy in a repair shop in Cairo might have a laptop which he has used to get content off the internet such as the latest phone ring tones or wallpapers. I like to think of it as a neighbourhood app store – and in many ways it’s the edges of the internet, where entrepreneurs are taking content online and offering it to local, offline and/or technologically illiterate customers. Also these corner shop app stores can be content editors for their community: they filter content they think their customers like, but they also guide what their customers might like as well. The strongest example of a high-tech hardware hack is the single SIM card that supports multiple phone numbers. In most African countries consumers want phones that support multiple SIM cards. This could be to have cards for different networks and save a bit of money by making calls within the same network, or it’s because a carrier may not have enough coverage throughout the country, or people want to separate work and social life or different parts of their social life (for instance, extra-marital affairs). Most manufacturers don’t offer multiple SIM card slots because, broadly speaking, they are selling through the operators, and this feature cuts into the operators’ revenue stream. However the demand is there, and we’ve seen street services that offer to take two physical sim cards, and re-engineer the circuitry to fit into one sim card slot – effectively allowing multiple phone numbers on one device. You could argue that the cutting edge of mobile technology and use is happening on the streets of places like Accra, rather than Tokyo or San Francisco. And they are networked. Five years ago if you went into any of these neighbourhood mobile phone hubs you would find repair manuals printed in black and white. A major company would put a phone on the market and within a month you would be able to buy a reverse-engineered repair manual. This is not something that Nokia or Motorola officially put out – a company in India or China would figure out this is how you fix stuff and they would transcribe that and mail it to Nigeria or wherever. About four years ago we started seeing manuals in colour, glossy, really well designed, they were being much more professional about sharing the knowledge. Now it’s all software-based and the latest information is picked up from the internet. On Monday it’s in London, by Friday it’s in Lagos and the rest of the world – there really isn’t a boundary now. All that means is, if anyone, anywhere in the world, figures out how to do something better and is able to monetise to their customer base, it rapidly spreads through this informal global network of repair and hack guys (and it’s nearly always men). It’s like the informal iTunes of software hacks. You can’t really think of Africa in isolation – it’s part of a global marketplace for ideas. For instance, when we were in Africa we saw an informal service called Sente (which is the Ugandan word for money). If I wanted to send you money, I would buy airtime in Kampala and instead of topping up the airtime on my phone, I would call you or text you the scratch-off code and then you would top up your phone. Now let’s say you don’t have a phone but there is a guy in your village who does. If I wanted to send you money, I would buy airtime here, I would call the local kiosk operator in your village and I would say, “My brother needs some money, I’m going to give you a code.” He would top up his phone and get one of the guys who hang around his kiosk to run and fetch you. When you came he would give you the equivalent cash to the scratch-off cards, but he would take a 20 or 30 percent commission. What fascinates me about services like Sente is that they are totally grass-roots evolved, there’s no central planning. So why does this practice happen there and why not here, in Los Angeles or London? What does it say about us and our culture that we don’t do that? Maybe we have much weaker social ties, there’s less trust. Maybe there are more alternatives for us, from a technological point of view. It’s not about right and wrong. It’s just: this is how it is. If you want to understand the cutting edge of physical hacks, you need to head to China and explore the shanzhai (bandit) culture. A model of phone that has been announced but is not yet on the shelves can be reverse-engineered in as little as two months and put on sale before the official phone hits the market. The quality of these phones varies considerably, from extremely poor, might-not-work-when-you-get-home, to virtually identical high-quality knock-offs. Many of these end up exported – and so there are at least two different types of phone on offer in Africa: the official products, and then phones by those shanzhai Chinese manufacturers, rebranded as a major manufacturer such as Nokia or Samsung. But there’s a lot of hacking (in the broadest sense of the word) that is driven by entrepreneurship, ingenuity and an understanding of how scarce resources can be put to good use. For Africans that don’t have access to reliable mains electricity there are street services where you take your phone and leave it with a guy, come back in two hours and your battery will be charged. To function as a phone kiosk – one only needs a mobile phone, phone credit and some way of calculating how much credit was consumed – so you tend to see a lot of mobile phone driven kiosks. Over time the guys that typically offer phone kiosk and recharging services are increasingly offering media content as well – anything from wallpapers and ringtones to installing applications. In many ways the phone kiosk operators are the telegraph operators of today: if you want to know what’s happening in the village, you speak to them because as communication hubs they also function as social hubs – people hang around, chat, and they get to overhear everything. The lesson from all of this for the large corporations and organisations I’ve worked with over the past decade is that for all of the resources at their disposal they need to stay fresh to what’s happening at the edges, because that’s where, driven by necessity, innovation keeps on moving on.

|

Image Martin O’Neil

Words Jan Chipchase

Interview William Wiles |

|

|

||