|

|

||

|

With her fantastical wardrobe and exuberant patterns, the east London designer was always going to get noticed. But behind the giant fruits and rainbow eyeliner is a thoughtful artist well able to control the noise There’s a down-the-rabbit-hole feeling as you draw back the heavy shutters to Bethan Laura Wood’s east London studio. In the young designer’s industrial base north of Hackney Marshes, certain things appear normal, while others seem to have grown fantastical in colour or proportion. There are books squeezed between giant hand-painted orange segments and blue patterned beans the size of handbags. There are plastic waste baskets sporting streaks of white and acid green that look like revered totems of influence rather than the everyday market tat they might ordinarily be taken for. And of course, there’s Wood herself. When she greets you, her unmistakable appearance – doll-like cheeks painted with pink circles, rainbow-coloured eyebrows, exotically drawn eyeliner and a mass of patterned layers that cover her from head to toe – marks her out as belonging to a peculiar tribe of one.

Shop window design for high summer, Hermès, 2014 Wood has said that her experimental dressing began in her school days, before her time at the Royal College of Art, from which she graduated in 2009. But it’s clear that today, the maximalist approaches to both fashion and design have become inextricable. Like Yayoi Kusama’s polka dots, Wood’s magpie attraction for patterns and colours – “an obsession,” she whispers – is the driver of her distinctive aesthetic across textiles, jewellery, furniture, lighting, set design and the many other fields in which she likes to work. She’s not naïve enough to think her persona doesn’t help to get her noticed, but she’s keen on her work being the main attraction. |

Words Riya Patel

Photography Catherine Hyland

Images: Angus Mill, Fernando Laposse, Nilufar Gallery, Fernando Laposse; Set design: Danny Hyland |

|

|

||

|

Guadalupe daybed for Kvadrat, 2014 |

||

|

The larger-than-life beans and oranges, Wood tells me, are the leftovers of Fruits of Labour, a major window-design project for French luxury house Hermès. To showcase a collection that included printed silk scarves inspired by the post-impressionist Henri Rousseau, she created a display that merged a hand-painted flat backdrop with foreground props given a similar treatment, playing between two and three dimensions. “My generic thinking of tropical is parrots and bright colours, but Rousseau’s paintings are that hot dark [sense of] tropic. I wanted to get that feeling of depth that suits the brand but in a way that was a bit me, and a bit English. So I ended up making giant fruit and vegetables.” Drawings of fruit pieces and patterns made from their skin pocks and surface textures became a rich source for Wood’s window treatment. “The painted way of working gave me the detail and noise I like, but without fighting with the products on display.”

Wood in her London studio among Hermès window props

A wall of Wood’s studio covered in process work and references Noise is a word that pops up again and again in the young designer’s vocabulary. Many of her projects show an extraordinary effort to achieve the level of detail she requires, often employing established craft techniques to achieve new interpretations. For Hermès, it was hand painting, and later assembling, thousands of beads for a Christmas window concept here in the UK. For the Particle furniture series with regular collaborator Nilufar Gallery (2013), she used a type of modern marquetry to cover cabinets in pieced-together wood laminate of different finishes. A puzzle with thousands of individual pieces, the hand assembly gives the impression of army camouflage or the aggressive patching of oriented-strand board. Last year, for Kvadrat’s Divina exhibition in Milan, she made Guadalupe, a dazzling daybed, with embroiderer Laura Lees, using appliqué and different colourways to vivid effect. It’s easy to think that the pursuit of such complexity might consign Wood to the realms of bespoke design, but she’s also been working on her first production piece, Rainbow. Surprisingly not a reference to the colours, but rather the arced shape of rainbows, the ceramic vases and candleholders were shown at the Ace Hotel during London Design Festival last year. |

||

|

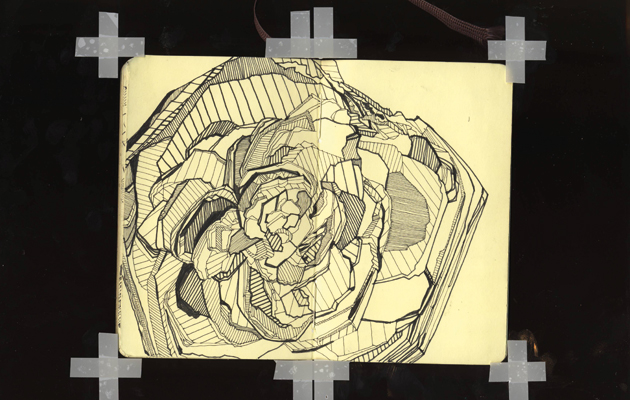

A sketchbook scan showing Wood’s method of observing |

||

|

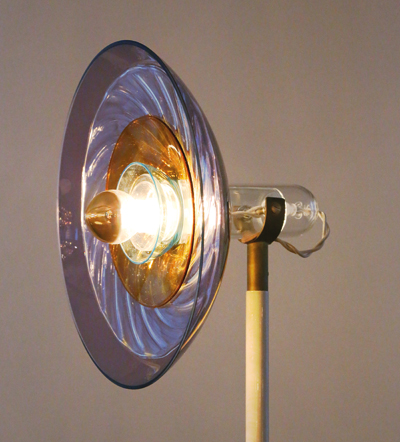

She acknowledges some of her labour-intensive practices are best suited to one-offs, but is quick to point out that industrial design isn’t inherently less complicated than limited edition: “Some very basic products involve complex precision. Take a toothbrush. It’s made from two to three types of plastic with different hardnesses. There’s all sorts going on in it, a huge amount of tooling. But because we don’t see that, and it’s produced at mass volume, we just accept it more.” As well as manipulating the small-scale aspects of her work, Wood takes care to add a layer of abstraction and ambiguity to the overall forms. “I try not to make my furniture too easy to read straight away,” she says. “With Totem [a set of Pyrex glass lamps made in 2011] I like that different people see different things: a robot, a jellyfish or a clown. I like to keep that ambiguity because that allows more space for the person who buys a piece to have a connection with it.”

Criss Cross table lamp, 2013

Moon Rock table, a private commission, 2011 Since a residency in Mexico City in 2013, the result of being chosen by W Hotels as one of its Designers of the Future that year, the country’s vibrant colours and culture have been a clear influence on Wood’s design and fashion. To beat the January chill of her studio, she offers to layer me up with some of her elaborate Mexican ponchos – a further surreal touch to my visit and something we agree she can pull off far better than I can. Accompanied by her Mexican assistant Fernando Laposse, the trip was an induction to the real Mexico, “not Google Mexico”, Wood says. “I’m a very visual person so the multi-sensory experience you get when you do a residency works really well for me in terms of new ideas.” Briefed with the question, “What happens when global is local and local is global?”, Wood was determined to seek out something other than the generic understanding of Mexican culture. The work she produced in response was Criss Cross: a collection of chandeliers, sconces and lamps (she calls them blooms) that reference Mexican flower garlands sold in the city’s street markets. The designs have interchangeable pieces that evoke the methods of arranging flowers. The “petals” were made with Mexican coloured-glass specialist Nouvel Studio, and the Pyrex connecting tubes were hand blown by glass artisan Pietro Viero in Italy, with whom she made Totem. Criss Cross interprets a unique aspect of Mexican culture without straying into cliche, and its candy-like range of colours, influenced by chilli sugar lollipops also found in the market, were a source of delight when debuted at Design Miami Basel in 2013, and later in Wood’s solo show at the Aram Gallery. |

||

|

Sketch of fruits for Hermès high summer window display |

||

|

Another Mexico City treasure formed the beginnings of the Guadalupe daybed. A chance visit to the New Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe, a modern design from 1976, introduced Wood to the stained-glass windows that would later inform her upholstery design. “I had no idea I would find this brutalist bonkers church and it was just off- the-hook amazing. My mouth was on the floor.” The windows are made of cast and stained glass set at angles that present different appearances depending on your view. The design for the daybed attempts to recreate the same feeling of depth and three dimensions through pattern placement and blocking. The design also incorporates rainbow embroidery, a Mexican craft Wood says she fell in love with while there. The technique is used to depict folk imagery in brightly coloured thread on areas of large cloth. “You’d think it would look childish, but for me it’s just beautiful. It’s the unexpected combination of all these vivid colours, puce-y pink and acid green, then knocked back with something like khaki.”

Wood with a fake fruit prop from her Hermès window display

Particle Construct cabinet for Nilufar Gallery, 2013 Like the laminate surface pattern for Particle, the embroidered upholstery for Guadalupe appears messy and random, but to both there is an underlying system that lends rigour. “Guadalupe is quite an intense piece, I find looking at its pattern relaxing but it’s not for everyone.” The pattern is arranged in strips and has a drop repeat so that one each strip slips down one panel or half a panel from the next. “That way you’ll always have a rhythm,” she says. “There is method to the madness.” For Particle, Wood used a tiling method borrowed from screen printing as the underlying system, then mixed and matched certain pieces by hand to hide the repeat. The measured attitude helps avoid the pitfalls of working with extreme pattern or bold colour. Wood’s projects are all the more impressive for suppressing the temptation to go all out, and instead display a mature handling of difficult tools that many designers avoid working with at all costs. “It’s about controlling colour without stifling it,” she says. “You can’t have it so unruly, so noisy that you can’t even focus on it. I enjoy a level of noise, and that’s what makes me different from other designers. When I graduated I felt I was able to make work that embraces the fact I can cope with colour and pattern, rather than try to strain it all the time because that’s what’s usually done.” |

||

|

Rainbow collection of vases and candleholders, 2014 |

||

|

She’s also aware that such a distinctive approach is susceptible to certain trends. Right now she’s in vogue, racking up commissions and awards, but no designer wants to be merely flavour of the month. “It’s helped me in some ways because the mass sphere of design has been accepting of colour and pattern for the last couple of years. When it goes out and becomes minimal again, I’ll have to see if I survive. But as a designer, you’ve got to embrace what you bring to the table. Otherwise why bother?” Wood’s interest in trends and styles is not fickle; she has a fascination for seeing how or why certain architectural or decoration styles fall in and out of favour over history, including cultural and commercial motives. Today she puts a general preference for neutral furniture down to the shifting mindset that homes are no longer outlets for individual expression, but financial assets to be later sold. Through her teaching at the École cantonale d’art de Lausanne, she’s been noticing technology’s influence on the research of design students, seeing the dangers of the ease of access to images via search engines. “You can get so reliant on only seeing what Google shows you, rather than researching and investigating more deeply. The longer we go on, the more things have been done not just once or twice before, but hundreds of times. And that’s a difficulty. There’s a danger of being able to see too much but not deeply enough to go anywhere else with it.” For a designer whose reference points are fruits, flowers, rainbows and candy, it can be surprising how serious Wood is. She is well-researched, making her observations the traditional way, through sketchbooks filled with meticulous drawings. She collaborates, bringing artisanal techniques back into the domain of the designer. And she is conscious of what it takes to succeed for a long time in the design industry. Her subversive, slightly barmy looks tells you nothing of these attributes at face value, but as I’m quickly learning, in the world of Bethan Laura Wood, not all is as it appears. This article first appeared in Icon 142: Colour. Buy back issues or subscribe to the magazine for more like this

Pattern for the Guadalupe daybed attached to a wall of Wood’s studio |

||