words Hadley Freeman

Vivienne Westwood has become what she never wanted to be: a national treasure, the status conferred by a V&A retrospective, which celebrates the work of the punk icon with a strong sense of tradition.

I’ve never really felt that Vivienne Westwood was for me. But then, the feeling was probably mutual. Certainly the one, brief and pretty unmemorable time that we met, the designer with a notorious penchant for eschewing airkissing for brutal honesty gave that impression. It was at one of those annoying “mwah-mwah, dahling, dahling” kind of fashion parties a few years ago. In all honesty, we both looked equally bored, but that was where the similarities ended. A well-meaning but patently misguided PR (is there any other kind?) attempted to introduce us and make us the best of friends: Westwood, in an enormous draped crinoline evening gown, replete with gallumphing bustle, took a skating glance at my typical couldn’t-care-less attire of jeans, Converse and blouse, and turned away. Westwood was not for me, and I was not for her.

Think about Vivienne Westwood’s clothes and the word “high” comes to mind: high octane, high cleavages and very, very high heels. For those of us with a more timid approach to dressing, such in-your-face style can seem, at best, as intimidating as the lady herself. Yet the woman who once proclaimed that she “never wants to be a national treasure” has been given the final confirmation that she is just that, with a retrospective of her work at the Victoria and Albert museum.

Funnily enough, the exhibition in this dusty museum makes a better case for Westwood’s current relevance than any of her recent runway shows, which might say something more about Claire Wilcox’s clever curatorship than the designer herself. This has been one of Westwood’s difficulties: just a decade or two ago, she seemed so forward-thinking, but now rightly complains that her shows no longer attract much attention. She is instead cherished with the kind of sickly sentimentality that she abhors. Has her moment passed, or is this just our inability to appreciate her in our own time? This show makes a pretty good argument for the latter.

The show opens with the “Let it Rock” clothes that Westwood made with Malcolm McLaren in 1971, which have, incredibly, survived the past three decades. Inevitably, these sneeringly punk creations are more interesting as cultural artefacts than fashion. Ditto for the day-glo sports clothes from her 1983 Witches collection (let’s all blame Jane Fonda for that decade of shame, OK?).

But it is in the second room that the best case is made for Westwood. In 1981, she began to study tailoring and looking to fashion history. Thus, we get the beautiful 1987 Harris Tweed collection, with its use of garments more commonly seen in 18th-century portraiture than on the King’s Road in the 1980s. The Princess Suit features a red riding jacket that seems to have come straight out of a Henry Fielding novel … although it is unlikely Fielding saw too many of them worn with a red miniskirt and dangling pom-poms. Her nipped-in, bias-cut tweed coats and miniskirts with bustles show an intelligent approach to fashion history, as opposed to someone pillaging it unthinkingly.

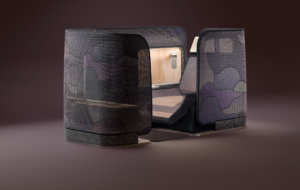

Fortuitously, the exhibition for this designer, who places such weight on construction and style, is itself superbly designed. Conceived by architects Azman Owens, the physical layout of the show leads the viewer around in a clever (but not too clever), clear-cut (but not didactic) linear manner. Examples of Westwood’s influences sit alongside the clothes that absorbed these ideas. So just yards from an 18th-century watercolour by Anna Maria Garthwaite is the coat splashed with a similar pattern. From ripped minis with zig-zagging zippers from her punk era, to her 1987 regal crown made out of tweed (“I like to keep it on when I’m having dinner,” Westwood said) and beyond, she has always been good on how large a role fashion plays in our national identity.

Plenty of designers have since taken a tongue-in-cheek approach to traditional British clothes (including Paul Smith, Bella Freud, Luella and Burberry), but Westwood not only did it first, she did it the most beautifully. It seems symbolic that Westwood’s waning star in the fashion firmament has coincided with Britain’s own diminishing status in the industry. But this exhibition makes a convincing argument that Westwood at least will have her moment again. Just don’t expect her to airkiss you in gratitude for it.

Hadley Freeman is fashion writer at the Guardian

Vivienne Westwood, V&A, London, until July 11