words William Wiles

For a “boy reporter”, Tintin never did very much actual reporting. The cartoon character never takes notes or worries about deadlines. It’s a pity in some ways, since in his 80 years on the world scene he uncovered myriad excellent stories. Gangsters, smugglers, jewel thieves, spies, even aliens and Bigfoot, all were investigated in the course of his career, and often thwarted too.

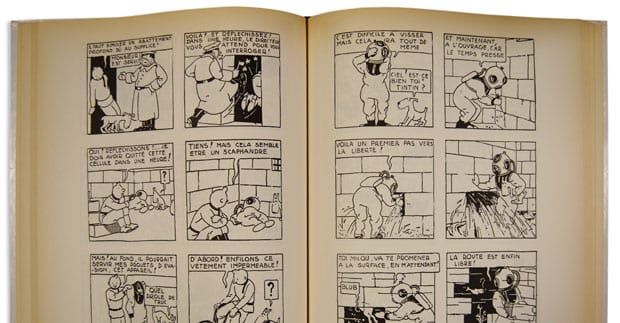

Tintin first appeared in January 1929, the creation of Georges Remi, a Belgian artist who went under the pseudonym Hergé. At first the stories were serialised in Le Petit Vingtième, the children’s supplement to the newspaper Vingtième Siècle (“20th Century”). The first adventure, Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, was graphically and politically crude and gave Tintin’s personality a vicious streak that is not seen in later books. The second adventure, Tintin in the Congo, is a colonialist romp filled with rhino-killing and racist stereotypes – it’s best forgotten. But the remaining 21 stories (22, including one unfinished work) are a wonderful canon of children’s adventure literature, and a rich compendium of design and satire.

The interesting thing about Tintin is that he isn’t very interesting. As a character, the boy reporter is a rather bland combination of deductive power, loyalty and virtue. The drama, comedy and mishaps that keep the plot moving nearly always come from the cast of supporting characters that surround him: Snowy, the wisecracking dog; Captain Haddock, the foulmouthed sea-dog; Professor Calculus, the absent-minded boffin; and Thomson and Thompson, the clumsy, incompetent private detectives.

The action takes place against a beautiful backdrop of intricately detailed street scenes and interiors. Hergé’s skill as an illustrator was coupled with a draughtsman’s eye for design. He also had a taste for mid-century modern design. Cars, buses, planes, speedboats and helicopters are rendered in fanatical detail. Packaging, advertising, furniture and whole buildings are minutely observed, even if they are disguised and moved – Oscar Niemeyer’s Palácio da Alvorada, for instance, is relocated from Brasilia to the fictional South American city of Tapiocapolis.

The series also had an enduring fascination with high technology – most memorably nuclear reactors and moon rockets in the 1950 adventures Destination Moon and Explorers on the Moon. But technological progress is a distinctly ambiguous force in the books. Professor Calculus, the inventor who represents science in many of the stories, is a distracted, infuriating figure. His inventions are more miss than hit – for every successful moonshot or submarine, there are multiple spectacular failures and explosions, or his discovery is used for evil and must be destroyed.

Come the end of the story, however, everything has been put right, and Tintin and his friends return to sexless bachelor stasis. The century wreaks its transformations around them, but they remain essentially the same.

In the third book, Tintin in America, there is a surreal scene where a city of sidewalks and skyscrapers springs up around him as he stands and watches. He has not moved, but suddenly his clothes are out of place. This moment is a foretaste of the series as a whole. Meticulously recreated Boeings and Chryslers aside, the Tintin stories from the 1930s look little different to those from the 1970s. Tintin is ageless and unchanging, still wearing the plus-fours of a pre-war Belgian youth well into the 1970s. And – early indiscretions aside – he is able to remain apart from the political compromises of a turbulent century. The Cold War barely figures. Tintin’s investigations are not part of a grander struggle; he is not affiliated with an ideology. Big business is the enemy as often as fascist agents or criminals.

Tintin watches modernity unfold without being corrupted by it. He is the personification of a 20th-century fantasy: to see the world change and remain unchanged.