words Justin McGuirk

At last, a book for the almost bare shelf labelled “design criticism”. But are we any closer to a general theory of stuff, asks Justin McGuirk.

Roland Barthes didn’t think consumerism and criticism were mutually exclusive. Neither did Jean Baudrillard or Reyner Banham. But there seems to have been something of a critical lull since the first full blossoming of consumerism in the Fifties and Sixties, when these writers were happy to dissect milk bottles and clipboards. Today, design is relegated somewhere behind fashion in the lighter pages of the Sunday supplements.

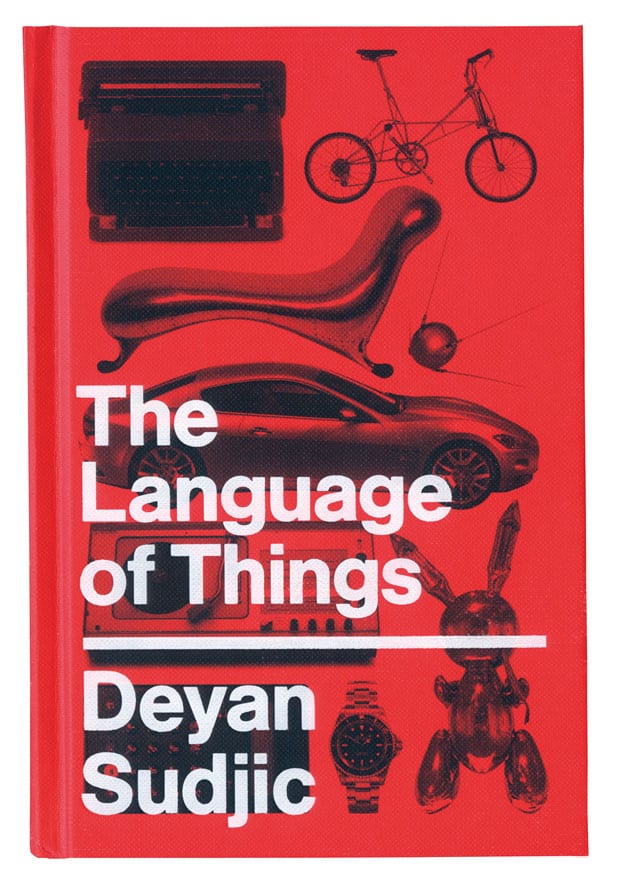

It’s a lack that Deyan Sudjic draws attention to in his introduction to The Language of Things. His ambition seems to have been to produce the contemporary design equivalent of John Berger’s 1972 classic analysis of visual culture, Ways of Seeing. However, there are also shades of Georges Perec’s novel, Things, and even, if only in the gravitas of the title, Michel Foucault’s The Order of Things. All very 1960s. The first paragraph – a catalogue of stuff we may or may not own – is highly reminiscent of Perec’s satire of a couple obsessed with what’s in the shops. But it’s the very first line that sets the tone: “Never have more of us had more possessions than we do now, even as we make less and less use of them.”

Unlike Barthes or Baudrillard or even Berger, who was distilling Marx and Walter Benjamin, Sudjic has no theoretical agenda. What he uses to navigate design, interestingly, is his own moral compass. He’s a critic trying to reconcile his fascination with the language of designed objects and his disapproval of the hold they have over us.

What was it, Sudjic asks, that made him absolutely have to buy that MacBook in an airport branch of Dixons? This is a more profound question than it sounds, one that leads him to explore the visual language with which a product signals its values – not just economic, but social and even national. The Helvetica typeface, the Citroen 2CV or the Apollo space capsule; each is seen as “a fragment of genetic code – a code that can grow into any kind of man-made artefact”.

Naturally, the devil of this argument is in the detail, and Sudjic gives himself the opportunity to scrutinise the nuts and bolts in a chapter on design archetypes, with particular attention to the Anglepoise lamp. It’s all worthwhile stuff but, for me, his strength as a critic is in nuance. He’s at his best making subtle but significant connections, like the one between the red dot on the safety catch of the Walther PPK and those on the Tizio desk lamp. He also has an eye for irony – why were Dieter Rams’ timeless designs no better at standing the test of time than Raymond Loewy’s, why do digital cameras still make the click of a shutter opening when there is no shutter?

Precisely because of the author’s moral misgivings, the chapter on luxury is the most assured in the book. “At a secular moment, in which neither magic nor religion – the original mainsprings of art – has quite the prestige that it once enjoyed, luxury can be understood as a synthetic alternative,” he writes. Quick to target the inanities of the luxury industry and the pointlessness of the diamond-encrusted electronics in Selfridge’s Wonder Room, Sudjic also takes pains to understand the language of the initiated spoken by the less vulgar rich, a language of shadow gaps and concealed stitching. After all, it’s one that we unconsciously aspire to.

The chapter that many readers will skip to, though, is the one titled “Art”, since the phenomenon some call “design art” or “gallery design” still awaits its defining text. What we need is an equivalent of Nicolas Bourriaud’s Relational Aesthetics, which helped the art world get its head around all that work that wasn’t exactly physical. But we may have to wait some time. Deft a writer though Sudjic is, on this topic he seems to be flailing around with the rest of us. The chapter is rife with questions, and limited by relying on “useful” and “useless” as lifejackets. “The more useless an object is, the more highly valued it will be,” he writes, inarguably. However, his conclusion that design bears “the burden of utility” feels not just too easy but a little out of date.

If only the design community was as comfortable as the art world with the idea of questioning itself, with the act of prodding its own boundaries. In my opinion, Sottsass showed us the way: “function” doesn’t have to be limited to use. Design can create sensations and experiences, it can signify and connote, it can question itself, all while sitting “uselessly” in the corner of a room.

We needed The Language of Things, and we need more books like it. It’s accessible, enjoyable and often thought-provoking. Perhaps it will be a bestseller. But we also need books that are polemical and opinionated and provide clear guidelines for examining any object – Berger’s Ways of Seeing managed this without sacrificing bestseller status. The Language of Things cruises along on insight, anecdote and information, but it lacks an ordering impulse. It lacks, to use that troublesome word, a theory.

The Language of Things, Deyan Sudjic, Allen Lane, £20