words Anna Bates

portraits Ulrike Myrzik

Stefan Diez hangs up the phone after a lengthy discussion with one of his clients. “I’m so tired of conversation,” he says. “People spend so much time talking, when we could just be doing.” The Munich-based designer is frustrated because his manufacturer clients – including Thonet, Wilkhahn and Rosenthal – don’t seem to get the way he works. His hands-on design process is more a result of trial and error than sketches and conversation – a process visible by the number of cardboard mock-ups piled in the corner of his studio. The space has an atmosphere of quiet concentration; a two-year-old girl attempts the splits, a baby lies on its back in the middle of the floor focused on the ceiling, while four workers are busying themselves with prototypes.

Diez is the model of what designers used to be before they became celebrities. His products aren’t loud – he is obsessive, quietly getting along, watching over every detail and ensuring that no short-cuts are taken. His work doesn’t grab at media attention, but connoisseurs know to look out for it – like word of a good craftsman used to get around – regardless of what brand is attached to it.

Diez’s design process starts with the material; it often involves manipulating a sheet. His Bent table for Moroso is made by perforating a sheet of metal and then folding it into a dining table – it is like origami for a circus strongman. His renowned Thonet 404 and 404F chairs consist of thin layers of wood, so the seat and back really give when you sit.

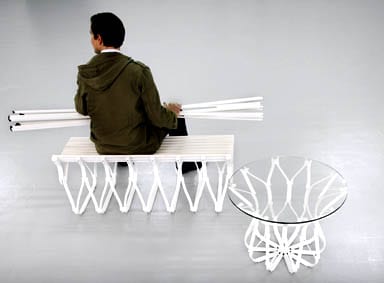

Diez’s language is one of technique rather than form. Not wanting to be held back by manufacturing limitations, he has even made his own tools. To make a coat rack and the structure for a bench and table for German manufacturer Schönbuch, sheets of metal are slit and bent, and then pulled apart like an accordian with a tool designed especially for the process. It’s nothing groundbreaking – a lot of the time he gives an alternative use to existing techniques by tweaking them slightly – but the tool didn’t exist in the dimensions needed and the manufacturer had to make a copy to go ahead with the project.

Like Jean Prouvé before him, Diez knows the structural integrity of metal. He uses the properties of the material in a super-efficient way, testing its limits. It isn’t heavily engineered like the French modernist’s – Diez’s furniture is more delicate – but it has the same sturdiness and is the result of an experimental process. “It gives you the feeling that you’re a pioneer,” Diez says. “It’s kind of human, to be an explorer. What else can we do as humans? I have no idea.”

Diez says he is the first male in his family not to become a carpenter. He grew up surrounded by machinery: “On Sunday, when my parents were sleeping I could use the dangerous ones,” he says. “I still have scars from the abuse of too big machines for too small a child.” He studied architecture and did an apprenticeship as a cabinetmaker, but frustrated by the idea that each piece is made just once, he became attracted to design and its promise of mass production. A course in industrial design in Stuttgart followed, as well as jobs for German industrial designer Richard Sapper, and his fellow Munich-based mentor Konstantin Grcic.

Grcic’s influence on Diez can’t be ignored. Diez argues that they both learned from each other – he took technology and handiwork to Grcic’s studio, and in turn got Grcic’s methodology and manufacturing contacts. With both, the shape and aesthetics originate from the process. But while Grcic has made multifaceted, multi-linear surfaces his trademark, Diez has a fondness for simple lines. He’s more the craftsman, with a machine and a computer.

Unfortunately, much of Diez’s time is spent trying to persuade manufacturers to act out his technical explorations. He thinks manufacturers’ “family business” ideology is holding back the industry. “We consider tradition to be something positive,” he says. “But we aren’t part of that first generation of designers who reinvented post-war modernism – we’re just living the dream of the last generation. After the war energy was put into being progressive. But now there’s a huge demand for harmony. People are closing their eyes to change.”

According to Diez, today’s designers deal mostly with marketing people who don’t understand them. “They aren’t interested in our stories,” he says. “They think they have stupid consumers, that they can put consumers into drawers with names. They think if you want to sell a wine glass you need to put a bottle of wine next to it. This is highly stupid.”

Diez is currently in a two-year long discussion with Wilkhahn to design a chair using machines and techniques from Germany’s signature industry, car-making. “There’s a correlation between building the chassis of a car and making a stool,” Diez says. “There’s the same flexibility and lightness.” Unfortunately, car manufacturers in Germany weren’t interested, so he ended up dealing with a more open-minded manufacturer in the Netherlands. Although production with Wilkhahn is looking hopeful, he is still concerned they’ll miss the point and try to mimic the shape using injection moulding. This is the problem when the story of a product evolves from the production process – the message can so easily get lost.

It is a similar, exhausting story for nearly all of Diez’s products – there is the cutlery

that came out 0.5mm too wide because the manufacturer wouldn’t use a different metal supplier, or the cooking pots that were made with handles in the wrong shape so they looked like “sad rabbit ears”. Then there are the glass pots with interchangeable porcelain lids that took two years to put on the market, because the glass was two euros more expensive than the manufacturer first thought.

“You know what happened?” he says. “It won a prize and now they have to do it. Someone grabbed them by their balls and said if you don’t do it, you don’t get the prize.”

He may sound exasperated but the truth is, Diez is addicted to the game. He enjoys being an “obstacle” and admits he finds the fight energising: “We as designers have to make sure manufacturers do products for our time. This is the only chance we have. These companies are editing and producing for our society.”

There’s something refreshingly solid about Diez. In a world where designers are increasingly bored of manufacturers and turning to galleries to produce their limited-edition pieces, it is reassuring that he is still doing design the traditional way and trying as best he can to move things on. His products quietly tell a story of machines and processes, of modernism in a new age.

All of Diez’s skills were combined in his biggest project to date – his live-work studio. In just half a year, the designer and his team transformed the carcass of an old workshop – rotten and fire-eaten – into a spacious, airy studio. “We did the whole thing like we’d do a piece of furniture,” he says. “This is the sketch – I just measured the space, and designed it as I worked on it.” He shows me a few squiggly lines, and I glare cautiously at the ceiling. “I have a good understanding of wood,” he says. “It bends before it breaks, so we’ll get a five-minute warning.”

The before-and-after shots have loaded up on his computer, and it becomes apparent that Diez is most proud of this project. We’ve been looking at the images of the studio in various stages of completion for half an hour. “Did you learn any new techniques you’ll use in your design work?” I ask, trying to progress, but he’s obsessively looking for another picture “of what it looked like before”.

The studio is home to his wife, a jewellery designer, and two children – the baby, now focusing on the floor, and the two-year-old girl who is sitting on one of the workers’ laps while he types on the computer: “It’s an office job – babysitting,” Diez says. The team is currently working on 15 projects; the bent and clamped tables and stools in front of me (made using the same technique as the 404 chairs) will be unclamped for Thonet in Milan. A prototype for Vitra of a “structureless” chair made entirely of fabric has just been finished (see intro, pages 17-21). But Diez’s biggest challenge is his new position as art director for German industrial design manufacturer Authentics. He has built a team of people he trusts around him, and they’re gearing up for something big. “I like to be able to control – I’m 100 per cent happy now.”

Click here to comment on this article

Shuttle containers, 2005, for Rosenthal, which combine glass bases with interchangeable porcelain tops for various functions

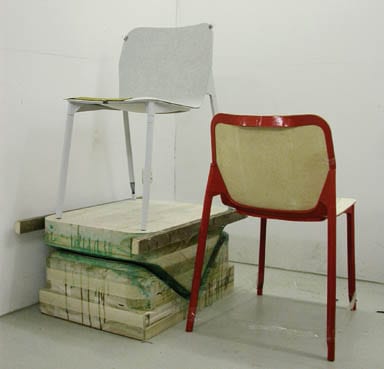

Cardboard prototype chairs for Wilkhahn. The plan is to make them using machinery from the automative industry

Oyster ring, 2007, for Jens Biegel, designed with the help of Diez’s jewellery designer wife

Bent table, 2007, for Moroso

Early utensil prototypes

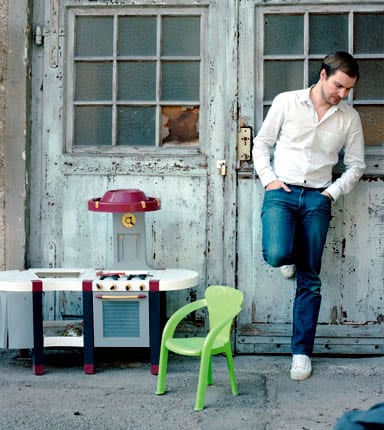

Diez outside his Munich studio, with his daughter’s kitchen

404 (in process) and 404F chairs, 2007, for Thonet, made of thin layers of wood that are bent, glued and clamped into shape

404 (in process) and 404F chairs, 2007, for Thonet, made of thin layers of wood that are bent, glued and clamped into shape

Upon bench, coat rack and table, 2007, for Schönbuch

Diez expanding the wood prototype for the Upon range

Diez expanding the wood prototype for the Upon range