words Sam Jacob

The Great Detective’s invented address on Baker Street is now the centre of a tourist interzone where a myth meshes with the real city in a storm of merchandise. Sam Jacob visits the home of Holmes.

Once a week, on my way to teach architecture, I would climb the steps at Baker Street tube station. Silhouetted against the Marylebone sky was the unmistakeable figure of Sherlock Holmes, or what, in fact, turned out to be a tall boy in an ill-fitting costume holding a pipe and looking bored.

Much of the area around Marylebone is littered with Sherlockiana. At almost every turn there are pipes, deerstalkers, aquiline profiles. From the tiles in the underground, to the statues, hotels, bars, cafes and streets, the ghost of Conan Doyle’s detective falls long and dark over Marylebone.

Sherlockopolis is an ephemeral crust applied over a pretty grim junction of two arterial roads. Here north London’s east-west and north-south routes collide at the fictional location of Holmes’ home, 221b Baker Street. But the Baker Street of Conan Doyle’s imagination evades us (after all, 221b Baker Street is not and never was a real address). In any case, this part of London was completely transformed by the Blitz and by more recent commercial development. The reality of the location and its imaginary version exist in perfect isolation, and so the veneer of Sherlockopolis is a kind of invocation, applied as if an accumulation of enough stuff will somehow make the fiction palpable. It’s also a touristic flypaper designed to make these unremarkable places sticky with Holmesian myth.

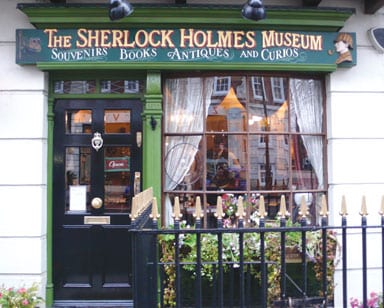

So let’s take a quick tour. Maybe we should start at Sherlock Mews, just off Paddington Street, where myth is summoned by name: an atmospheric alley that becomes, under this moniker, a piece of Victorian scenography rich with imaginings of crime. Perhaps you might stay at the Park Plaza Sherlock Holmes Hotel, which toys listlessly with Holmesian iconography. Its name is applied in corporate lettering with an “E” missing. You might dine at Sherlock’s Bar and Grill, enjoying a current half-price deal. You’ll have to visit the Sherlock Holmes Museum at 239 Baker St (though through a loophole in legislation which allows a limited company to display its name without planning permission, its address reads “221b” in historically authentic gold script). Inside, period costumed youths staff the shop. Here you can browse ceramic figurines of Holmes and Watson, there are pipes of varied sizes and stacks of deerstalkers. Upstairs, rooms stuffed with junk-shop Victoriana approximate an idea of Holmes’ quarters. Bad waxworks act out dramatic moments from the Holmes canon. Afterwards, you might head to the Sherlock Holmes Food & Beverages, where you can order double egg and chips surrounded by low-grade murals depicting Holmes’ adventures.

Through all of this and more, the urban reality is warped by a fictional idea. We might wonder how this fictional idea differs from the reality. Perhaps heritage, as we understand it in architecture and planning, is not real either – for real history can’t help but become fictional when it is articulated and represented. Perhaps all cities exist between narrative and the physical reality of stuff, and that’s why Sherlockopolis is more than an ephemeral joke. Though its own story is fictional, its cultural meaning is concrete. We might think of it as fictional-historical-futurology, a retro-projection that maps out potentials.

Detective fiction from Conan Doyle to Raymond Chandler to The Wire always contains a form of urban critique. Through its narrative we read our way through the hopes and fears of a city. The Holmes stories were written at a time of urban turmoil, amid the aftermath of the industrial revolution and the massive Victorian expansion of London. The urban landscape was in rapid flux, transformed by modernity. This new metropolis was shot through with fear, which detective fiction articulates as crime. In urbanism, the very same fears drove the development of the suburbs (an escape via infrastructure) and later the modernist utopian visions (remember Le Corbusier’s warning “architecture or revolution”).

In this context, we might read Holmes as a figure of urban salvation. As he remarks in the Adventure of the Copper Beeches: “The lowest and vilest alleys in London do not present a more dreadful record of sin than does the smiling and beautiful countryside.” Maybe that silhouette at Baker Street Tube was there to remind architecture tutors heading to the University of Westminster of the dramatic imperative of urbanism.