words Owen Hatherley

In an attempt to escape painting, two dynamic constructivists prefigured the 20th century’s art mainstream, says Owen Hatherley.

It’s only been a year since the Hayward offered us a retrospective (icon 058), so why another outing for Alexander Rodchenko? The question is easily answered. The Hayward concentrated solely on his photography. And by concentrating on him exclusively, with only a walk-on part for wife Varvara Stepanova, that show elevated him above his constructivist contemporaries. Here he shares billing with another artist who is very much his equal: painter, graphic artist, fabric designer and experimental architect Liubov Popova. And the objects on show range from slim volumes of poetry, to films, to architectonic reconstructions.

Even so, given that constructivism was a deeply collectivist movement, and given that the exhibition also features works by Alexander Exter, Alexander Vesnin and Stepanova, it seems odd to concentrate on just these two. Still, curator Margarita Tupitsyn’s excellent commentary and selection eschew the customary victor’s justice.

Any overview of constructivism will come up against their loathing for and attempted destruction of the gallery and the museum. Tate Modern, which combines both, would have horrified them. Yet the strict chronological order here is enlightening. We begin with two wildly talented abstractionists, their lines, planes and polygons both disciplined and dynamic.

Brilliant as this is, the real story is what happens next. Frustrated by the limitations of painting, they go through an extraordinary attempt to define exactly what these limits are, with experiments that prefigure and usually surpass the next 80 years of art. Here you’ll find the accidental invention of minimalism, abstract expressionism, kinetic sculpture, op art and pop art. All, however, are quickly discarded, for when they declared “the end of painting”, it wasn’t hyperbole – they had taken canvas as far as it could go.

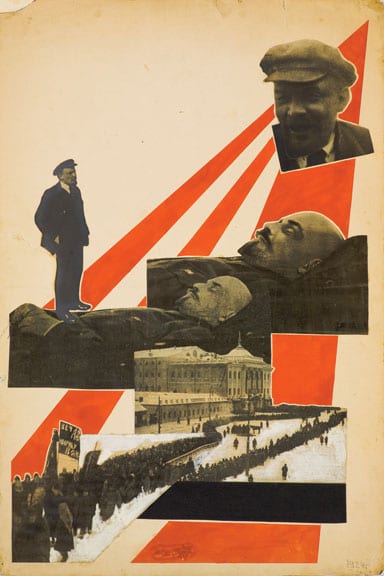

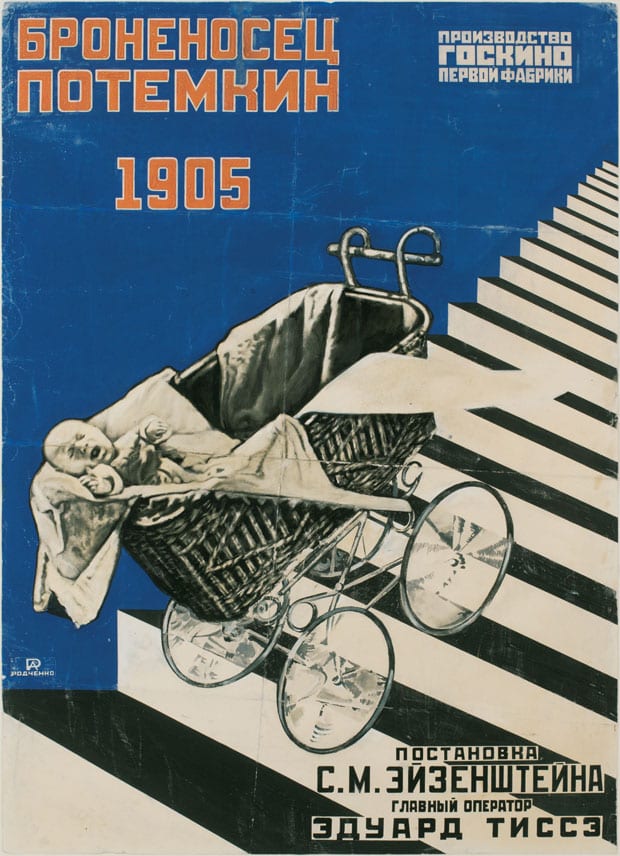

Rodchenko and Popova’s opposition to painting was not mere utilitarianism, but a disdain for the mythic aura of the artist and the original artwork, and of the passivity induced by the gallery and the museum. Constructivism intended to escape art, to engage in the new spaces of everyday life. So it spilled into the street, in the form of adverts, posters and Popova’s abstract fabric designs. It entered the world of cinema, for which Rodchenko designed titles and sets. And most of all, it embraced architecture – even works on canvas were described as “Painterly Architectonics”.

This creation of new space was the overwhelming constructivist concern. Yet the exhibition mostly takes place in 19th-century space. Films are featured, but clumsily: 23 minutes of Vertov’s Kino Pravda plays on a small screen to a room without seats, while six minutes of Kuleshov’s The Female Journalist plays to leather couches.

The exhibition ends, finally and exhilaratingly, in 20th-century space, in the form of a room reconstructing the interior of Rodchenko and the architect Konstantin Melnikov’s Pavilion for the 1925 Paris Expo. This “Workers Club” is a heady collision of sharp reds, blacks and greys, where Rodchenko’s abstractions become elegantly functionalist furniture, arranged in a collective line around a table of books. Happily, the space is designed to be used, and visitors can read the material supplied – The Independent rather than the Morning Star, alas. Melnikov later wrote of this building that “in my architecture I fought against the idea of the ‘palace’ and in its interior Rodchenko fought against the idea of the ‘shop”.’ Here, as soon as you leave the reconstructed club you’re in the Tate Shop, where you can buy all manner of constructivist merch.

Rodchenko & Popova is at Tate Modern, London, until 17 May