words Richard Wentworth

Artist Richard Wentworth collaborated with architect Caruso St John on the landscaped square outside the New Art Gallery Walsall. Here he describes his approach, and explores the idea of surface in contemporary culture from motorway blacktop and aeroplane wings to Mickey Mouse striped paint.

I write. you read. I am the writer. You are the reader. (We don’t know each other.) How may we connect the spaces between us?

Let us imagine, perhaps, all the procedures of our lives, and list the reciprocating verbs and nouns which we employ to describe our intersecting narratives. Does the paviour meet the pedestrian? Is the paviour the pedestrian?

Wherever you are reading this, look down to the surface that supports you. Would you call it “floor” or “ground”? Is it “personal” or “public”? Is it “soft” or “hard”? “Interior” or “exterior”? Is it “level” or “contoured”? Is it “made of itself”? Perhaps “what you see is what you get” or do you sense some underlying structure which supports the surface? Is it “granular” or “fibrous”? “Warm” or “cold”? Could you name its components and how they are organised? However you choose to describe the surface beneath you, can you also define its limits? Can you see its curtilage, or does it run away beyond your vision? Is it a continuous, rhythmic skin which collides, eventually, with other surfaces? When it does, is there a change in level? Is the next space defining a more, or less, public realm? As you chase these surfaces with your eyes, or feel them with your feet, how do these meanings change?

When, in 1997, I was first invited by Peter Jenkinson, the director of the then unbuilt New Art Gallery Walsall, to collaborate with its architects Peter St John and Adam Caruso, the site harboured many ambiguities. A piece of remaindered land, a grassed-over dog patch, vaguely contoured around the canal arm, which sat like a magnificent spirit level amidst two or three metres of ups and two or three metres of downs.

The commissioning process is often grim, because “somebody knows what they want” (and hopes to get it). The open-ended, yet welcoming, terms of my invitation were as stimulatingly terrifying as the demands of any creative act should be. In French, there is one word for guest and host.

In the knowledge that Peter and Adam planned an assertive vertical building for the gallery, and hearing their enthusiasms for its materials and scale, I thought carefully about the traditions of totemic objects in public spaces. Perhaps I could go the other way, leaving architecture in charge of things that stand up (and out), and pursue a relentless policy of land grabbing. In time it became obvious that the New Art Gallery would become Walsall’s very own belvedere, so that my instinct to ground my work in the ground itself seemed more like providing a view for the surveyors of the future, or making “sea” for the look-out.

The ambition to colonise a large piece of the town, irrespective of property rights, has strong military references, but also rhymes with the way a red carpet can be used to elevate the status of a space. It is also not so different from that most modest act of possession, painting a rented flat from a single bucket of paint, ceilings, walls, floors, and all.

At an urban scale the differences are obvious. The scale of diplomacy and the large numbers of overlapping agencies and personnel who need to be persuaded is the quick way for artists to understand why others become architects. In England, where the sensibility to public space is typically no more sophisticated than a patio in Hampshire, these diplomacies are an artform all of their own. In this instance, perhaps, they were a metaphor for my underlying purpose. With a great deal of support (and guile) from Peter Jenkinson who is blessed with a natural sense of politics, Peter St John, Adam Caruso, and the landscape designer Lyan Kinnear, we edged towards my version of local land reform. The trump card arrived scarily late in the process when Peter Jenkinson obtained the long reach of the canal towpath, or, at least, the right to treat its surface.

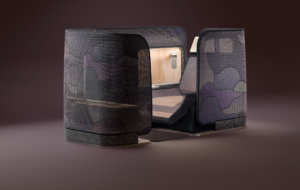

The grandeur of my proposal was that the contoured totality should be handled with the gorgeous uniformity of motorway blacktop, an anonymous craft which is one of the very best things that we do. Skilled, anonymous, unsung, with military and airfield overtones. Made for driving, but beautiful to walk upon, I also remember thinking that if you took the banding language of cabinet-making and marquetry, and changed its scale, it should be possible to generate a space that would fall somewhere between surface-as-decoration, and surface-as-sign (as in tennis courts, car parks, or the high-speed imperatives of road markings).

At Walsall, the success of the absurdly wide banding is that it shows up the proportions of the different spaces it encounters. Like a pot of Mickey Mouse Stripe Paint, it visits every corner of the extended (and extensive) site with equal disrespect. The stripes fall with the geometrical inevitability of shadows before a light source. Gallery Square argues with its new title, a collection, in truth, of dog legs, off shoots, cul-de-sacs, forecourts and promontories which take you away from, as much as they lead you towards, the New Art Gallery. The ground functions with a kind of democratic, celebratory flair, so that its users always appear both ennobled and cherished. It is a space I would enjoy showing both to Giacometti and de Chirico, preferably at the same time. In much the way that their work enjoys an enormous secondary audience by means of postcards, Peter Jenkinson and I always imagined the banded heraldry of Gallery Square enjoying another audience who might glimpse it from the air, know it from a postcard, or know it only as an urban myth, echoed every time they use a zebra crossing.

So where is the writer writing? Over France? Over the Atlantic? Over South America? Looking out of the window of the plane at a wing as long as the street where I live, as wide as a Walsall stripe. The reverie of flight is reinforced by the effects of light on the surface of the wing. Its structure and material seem miraculous, un-nameable. Its gloss and sheen are how our culture will be identified. I can read two words: “NO STEP”.

This article was first published in Scroope: the Cambridge Architectural Journal, and is reproduced with the consent of its editors. Scroope is published annually: details from [email protected]