words Anna Bates

It’s the fourth biggest furniture manufacturer in the world, and there’s plenty of local creative talent. So why is Polish design stuck in a rut, asks Anna Bates.

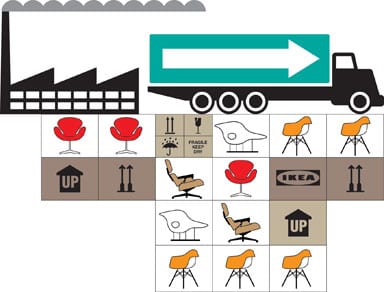

Down a dirt track on the outskirts of Warsaw, 24,000 pieces of Polish design are hidden in a dusty mansion. Mostly prototypes, the furniture, textile and ceramic pieces from the early 20th century to the present are stacked in the National Museum’s storage, room after room documenting the country’s failed design history. At the same time, Poland’s well-oiled assembly lines have made the country the biggest furniture production powerhouse you never knew about. Poland is the fourth biggest manufacturer of furniture and design in the world, after China, Italy and Germany. Vitra, Thonet, Fritz Hansen, Kinnarps and BoConcept all use Polish manufacturers; the mug you’re drinking from is probably made there too because Tesco, John Lewis and Ikea have products churning out of the country’s factories.

So why is Poland’s design heritage collecting dust? And why, when I meet some of the country’s most promising young designers, do they say they’ve never bothered to approach a Polish manufacturer to produce their work? Until now, there’s been little communication between industry and artist, but it seems things are beginning to change. A handful of manufacturers including furniture companies Noti and Vox and traditional upholstery brand Iker are trying to raise the standard of design in the country using local talent. Lodz (a city to the south west of Warsaw, pronounced woodge) is holding its second design festival, so I’ve come here to find out how designers and manufacturers got into this muddle, and what lies ahead for the them.

Since Thonet produced some of its chairs in Poland in 1870, the country has been the outsourcers’ friend. By the 1960s, after the devastation of the Second World War and decades of Soviet domination, it was fully operating as Europe’s cheap furniture slave.

“And for good reason – it was about jobs and people’s lives,” says David Crowley, curator of the Cold War Modern exhibition at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum. “Manufacturers were really just concerned with keeping their businesses operating. Philippe Starck would have been the last person Poland needed at that stage – it needed a pragmatic view.”

Meanwhile, manufacturers producing for the home market got away with selling cheap, low-quality furniture to Poles starved of resources “who would buy anything,” says Bogna Swiatkowska, director of the Bec Zmiana Foundation, a cultural group. “I remember queuing for food, shoes, clothes – everything. More advanced products weren’t even thought of.”

But several decades later, free from Soviet dominance, and with a growing economy, things haven’t really progressed: “If something functions, it is still fully enough for people living in Poland,” says Swiatkowska. Lukasz Drgas, an art historian who owns Magazyn Praga, a design concept store on the edgier side of town, says that the onus is on consumers: “These companies that offer ugly stuff, they sell very well – why would they do something different? There isn’t a tradition of design in Poland. If people buy design it’s a bit similar to Russia – people with money will buy a name, like Starck’s Louis Ghost chair. My view is very black.”

Drgas is cynical because Poland failed to develop a design culture, even after repeated pushes. From 1904, it had the Warsaw School of Fine Arts – Poland’s answer to the Bauhaus – and later the Communist government established the Institute of Industrial Design, whose mission was to forge the collaboration between design and industry. “But it just didn’t happen,” says Anna Frackiewicz, curator of the industrial design department at the National Museum in Warsaw. “The industry wasn’t interested, there was no incentive – it was a socialist economy of lack.”

Although some products were mass-produced, most design was commissioned by the government to “show off” to the West at international trade fairs. Crowley explains: “There was no interest on the part of state factories to realise their ideas. The designs just stayed on the shelf or on the pages of design magazines, where they functioned as useful propaganda. There is something terrible about this in terms of the experience of ordinary people – you can look but don’t touch.”

Back at that mansion outside Warsaw, you’ll find the former Eastern bloc’s answer to the Eameses and Marcel Breuer – experiments in bent wood, fibreglass, and cantilever tubular steel – stacked on industrial shelving. Uncredited, the works are in rights limbo, so whenever the National Museum tries to put pieces into production it hits a brick wall.

After years of disengagement by the industry, designers are used to taking solace in unrealisable artistic projects. “Manufacturer” is seen as an ugly word in Polish educational institutions, where designers are trained to think as artists. Yet this has its advantages: “We know it won’t give us money, so we can just be creative,” says Zofia Strumillo-Sukiennik from conceptual design group Beza Projekt. Marta Bialecka from La Polka says “furniture design is a hobby for us all, more or less,” explaining that the collectives fund their fun by working full time in other jobs. To some, the idea of selling their work is so far off they give it away free.

But Poland is not the same country it was five years ago, and there’s evidence some Polish manufacturers are starting to adjust. Iker recently commissioned Poland’s young design star Tomek Rygalik (who comes with Moroso’s stamp of approval). “Some manufacturers are already sensing the new direction the market is taking,” explains Rygalik. Noti, Iker’s competitor, is also working with Rygalik because it thinks Poland’s expats – from graduates to cleaners – will return to the country as more refined consumers, “looking for good design,” says the manufacturer’s sales manager Irena Krzywonos.

With its economy continuing to grow, Poland seems to be well placed to weather the recession. There’s also something of a cultural revolution going on: “A lot of young people hate the government,” says Crowley. “So there’s this incredibly tense atmosphere that’s having a great influence on literature and art. I think design is getting some of that.” Rygalik thinks this energy has triggered manufacturers’ change of heart. “They know design is the trajectory they need to take to be able to compete,” says Rygalik. “But they also have a bit of vision.”

Lodz Design 2008 was a sure example of this enthusiasm. Like a jumbo version of Milan’s young designers showcase, Salone Satellite, the fair was full of hope, despite the conspicuous absence of Polish manufacturers. Curated by the former editor of the Polish Elle Decor, Agnieszka Jacobson-Cielecka, it showed several products by Polish designers that were already in production with companies outside Poland – such as Oskar Zieta’s Plopp Stool for Danish company HAY.

Educational institutions seem to have tweaked their philosophy – there were a surprising number of practical ideas on display from the country’s younger designers. Rygalik, who teaches Design and Design Management at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, has been working hard to change the way Polish designers think, encouraging students to work in a way that will make them more accessible to the industry.

Rygalik is also working on the flip side, giving lectures to manufacturers on the importance of designers in industry. Something seems to be working: in a recent poll by the government, 76 per cent of manufacturers in Poland said design was vital to their future. “Even companies that produced furniture for the high street are starting to build new brands and use designers,” says Krzywonos.

There’s still a lot of work to do – the furniture being produced by Poland’s most avant-garde manufacturers is still not ready for the Milan furniture fair. But it’s in confidence that the biggest development can be seen. Polish manufacturers are starting to assert themselves. Until now, Poland hasn’t even branded its wares with a “made in” sticker – one high street design company even gave itself an Italian name. What’s more, the European brands that commission the manufacturers are secretive about who they work with.

“Poland has been in a state of war for a long time – it is embedded in local psychology,” says Rygalik. “But sooner or later, it’s going to come out of it. It’s just a matter of gaining confidence – maybe design is a good tool to create this confidence.”

Illustration Anthony Burrill