words Daniel Miller

The speculative megastructures of the 1960s weren’t just utopian dreaminess, they were entirely practical. So let’s drop the nostalgia, says Daniel Miller.

Visitors enter Megastructure Reloaded through a polythene tunnel arched over a pale blue floor. This spills into a courtyard, where a number of mysterious water-filled blobs are held overhead by a mesh of cables. Welcome to the future, 1960s style, when communes walked the earth and visionary urban speculation was fevered.

The exhibition design of Megastructure Reloaded is the brainchild of Archigram member Dennis Crompton and the young Berlin firm Raumlabor. Their joint-brief was to convert the sprawling expanse of Berlin’s former State Mint into an improvised exhibition space, showcasing on the one hand original work from the Sixties and Seventies, and on the other, thematically-related contributions from contemporary artists. Hence Kim Swang wittily reinterprets the plans for Plug-In City from Archigram 7 in the form of a model toy kit, while Franka Hornschmeyer focuses on the architecture of the very small, supplying a disquieting labyrinth of many doors that initially disturbed me into thinking it was the entrance to the toilets. But most entrancing of all are Vincent Nieuwenhuys’ visionary video fly-throughs of his father Constant’s New Babylon, still the glittering diamond of all speculative urbanism, and the standard for all of the megastructures that followed.

The second half of the show is taken up with those megastructures, showing the diagrams, films, provocations and pamphlets of all the principal plotters: Superstudio, Archizoom, Yona Friedman, and Archigram itself. There is some danger in conflating all these different groups – as the theorist Kazys Varnelis has pointed out, while Archigram would have been delighted to build if it had only been given the chance, Superstudio and Archizoom thought of architecture principally as a means of critiquing society.

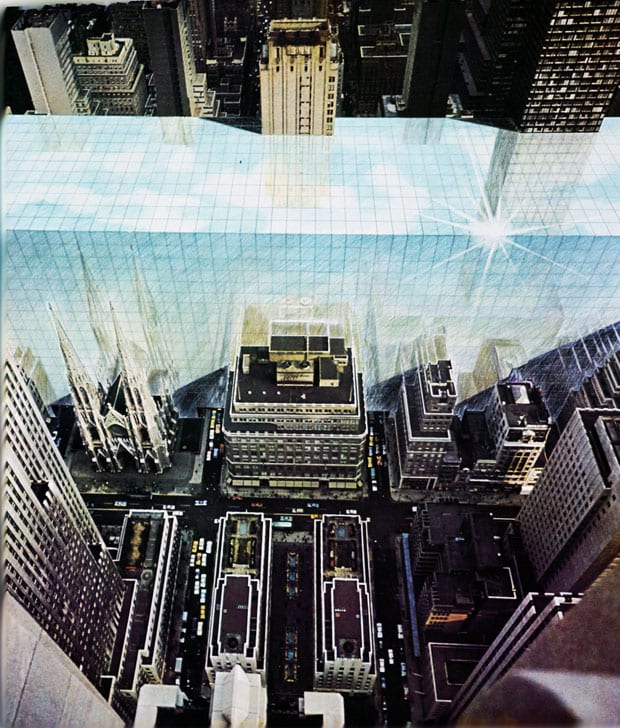

The principal merit of this show is to make clear that the notion of megastructures was never as mad as it has sometimes appeared. Working in the understanding that, as Archigram put it, “cities are first a number of events and only secondly a collection of buildings”, the fundamental ambition that the megastructuralists shared was to envision a large-scale urban logistics capable of supporting more dynamic patterns of social interaction than the obsolete patterns of the past. In this way, the concept was related to the eminently practical way that the really-existing megastructures of the sewage system and the electrical grid provide rational frameworks of sanitation and power.

The irony is that something like this has in fact occurred. Thanks to the internet – perhaps the largest megastructure ever devised – a new urban logic is taking shape, and reformatting all of the old industrial cities around it. “A computer makes a city seem almost unnecessary,” the artist Vito Acconci once noted, and while this is an overstatement, it bears within it a truth.

Megastructure Reloaded is a fascinating and erudite exhibition, but it doesn’t engage with this issue, and thus seems in some ways backward-looking. Although the utopian speculation of the Sixties and Seventies was stunningly fertile, it is nostalgic to excessively privilege it, and this show is about the future as it once was, rather than the present as it is. Visionary planners once thought they could invent new kinds of spaces, but it was new forms of media that actually did invent them. Clearly, the relation between the imaginary and the real is never a straightforward one. Yet programmatically speaking I cannot help feeling that the contemporary challenge is not to reload the megastructures of the Sixties, but to surpass them.

Megastructure Reloaded is at the former State Mint, Berlin, until 2 November megastructure-reloaded.org