words Anna Bates

portraits Annie Collinge

What is Marije Vogelzang? “I think I’ve got it, you’re a visual artist,” says chef Michael Smith, Canada’s answer to Jamie Oliver. “Actually, I think of myself as a story artist,” says Vogelzang. Later on, she gives me a completely different answer. Either she’s playing games or she’s still trying to figure it out. Her business card says “designer”.

Smith is in Vogelzang’s Amsterdam studio with a Canadian TV crew making a programme about food, not design. They’re using her to represent the Netherlands in

a show about global cuisine and they want to film her preparing a dinner. Food is Vogelzang’s raw material, but she’s not interested in merely shaping it. “I’m not a person who makes shapes – like Starck and his pasta,” she says. “And I don’t decorate it – I’m not a food designer.” Instead, she styles herself as an “eating designer”. It’s about the way we experience food. “I use food to communicate my ideas. It’s about the verb of eating. It could be the harvesting, cooking, eating or going to the toilet afterwards.”

Perhaps it’s easier just to describe what Vogelzang does. She recently used an empty reservoir basin to host a tasting of the Netherlands’ 12 different tap waters. She likes to subvert the way we think about our daily rituals – treating water we flush down toilets as a wine-like delicacy. In a project for a physics conference she made a wooden tree covered with anglepoise lamps on which small dough pancakes were baked, exploring the process of photosynthesis. “Instead of turning carbon dioxide and water into carbohydrates and oxygen using sunlight,” she says, “we turned electric light into crispy, edible leaves by baking the dough on the lightbulbs – it’s a poetic approach to physics.” Each project involves extensive research so she can prepare food that is relevant to the eaters. There’s no doubt that her working process is that of a designer’s.

Vogelzang’s studio – a converted gasworks in the middle of a park – smells of apples and cinnamon (a dish we eat for dinner). The TV crew has given us half an hour to shoot her. She’s in a playful mood and convinces us to photograph her with Arianne the chicken on her head. There’s a brief kerfuffle – Arianne flies clumsily at the flash, knocking it to the floor – before the two settle down, posing comfortably in position for 20 minutes.

But it’s not until midnight that we get to talk at length. She pours us a whisky: “I was doing the food at Jurgen Bey’s wedding and this entrepreneur asked if I wanted my own shop. I quit my job with Hella Jongerius, but the site for the shop fell through. I had no money, no job, so I thought – let’s get pregnant. Then the entrepreneur found another space.” This is typical Vogelzang dialogue. The 29-year-old designer switches between characters – sometimes she’s your stereotypical eco-concerned vegetable grower, sometimes she’s like a mischievous pixie, smiling cheekily while you ask her questions and replying with a string of flippant remarks. She brings both of these personalities to her work – at once trying to help obese children curb their eating addiction, while simultaneously making extremely sugary sweets for toothless elderly people, “because, what the heck, they have no teeth.”

Her first shop – called Proef (meaning “to taste/test” in Dutch) – opened in Rotterdam in 2004. The cafe serves good, plain food, with an occasionally conceptual approach, but mostly it gave Vogelzang an income and an opportunity to work on projects. In 2006 she moved to Amsterdam and opened her second Proef, this time using the space solely to work on projects (and renting it out for dinner parties at a hefty fee).

Vogelzang was born in Enschede, a city in the eastern Netherlands, and she wasn’t brought up to be concerned with food. She enrolled in the heavily conceptual “man and leisure” course at Design Academy Eindhoven in 1995 to get away from home. “I was completely adolescent, I had no idea what I was doing – I nearly got kicked out,” she recalls. “That’s when I realised I had to start doing things that would make me happy rather than trying to please the teachers.” So she ignored “technical” materials such as wood and metals and started working with food.

In her final year, Vogelzang designed a funeral. “I wanted it to be an alternative to the Dutch ritual of coffee, sponge cake, everyone in black,” she says. Instead she presented a dinner where the food, clothing – everything – was white. Choosing a colour many non-Western cultures associate with death, she created a more serene, spiritual environment. Whether grievers would care for a quail’s egg and bean sprout snack is besides the point – the important thing is that Vogelzang created an environment that encouraged interaction, where people could share memories and stories of the deceased, and she lifted the heavy gloom normally surrounding funerals to a feeling of spirituality and togetherness: “It’s about sharing food together,” she says. “Which I think is healing for the body and the soul.”

The funeral was archetypal Vogelzang – she far prefers experiences to objects: “I always want things to be used, I’m really happy I’m not just making more stuff.” By using food she can bypass materialism and work directly on people’s emotions. Food is, after all, filled with emotional associations. “It’s comforting,” she says. “It’s very much related to childhood – when it was your mum who fed and comforted you. That’s why people have so many eating disorders. Because when you were sad your mum comforted you with food. As a designer, to come so close to someone’s personal emotion is something I don’t think you can do with any other material.”

Despite her unique choices when it comes to the raw materials for design, Vogelzang is still the product of a scene. She studied alongside fellow Dutch designers Wieki Somers and Chris Kabel; around her neck is a piece by Amsterdam-based designer Ted Noten (icon 052) – a fly and a pearl encased in acrylic and hung from a silver chain. She says she feels “quite strongly rooted” in the second generation of heavily conceptual Dutch designers to have emerged from Eindhoven. “I don’t know if that’s a good thing,” she adds, because the Dutch, or more precisely Droog, approach has been criticised for producing ideas over usable products. But her work is anything but purely theoretical – there’s nothing more functional than eating.

So dinner at Vogelzang’s this evening is a trademark combination of the prosaic and the exotic. She has decided to treat the Canadians to the traditional staples of the Dutch peasant – salsify (poor man’s asparagus), a damp mackerel and a small, cold onion. It’s not a gastronomic delight, but Vogelzang isn’t aiming for a Michelin star, she’s aiming to tell a story. Our dinner could be one that her ancestors ate hundreds of years ago – a thought that a heavy garlic and butter dressing would completely distract you from. The dinner plays heavily with ritual – we were welcomed with strings of apple peel placed around our necks, to wish us long healthy lives. For Vogelzang the sense of ritual is closely linked with a sense of play – she likes to use objects in an unconventional, whimsical way. She frequently uses office lamps as cooking tools – for the dessert, we place chocolate pots of whipped cream under anglepoise lights to melt them, just because it’s fun.

People are always the key to Vogelzang’s projects. She was recently invited to do a project in Beirut by Kamal Mouzawak, founder of Lebanon’s first farmer’s market. “Everything is destroyed in Lebanon,” says Vogelzang. “People lost their culture, their heritage, their background. Mouzawak wanted to give people back their sense of culinary culture, and make inhabitants proud of their country again.” Instead of coming up with the story herself, Vogelzang asked the locals to provide it – she asked 100 people about their food memories, and specifically what food they associated with war. “Lots of people said bread was a war food,” she says. So with a small group of “rich, poor, Christians, Muslims, farmers and shop owners”, Vogelzang orchestrated a “green line” of bread bowls (coloured with parsley juice – a Lebanese staple). The green line was the border that separated the mainly Muslim factions in West Beirut from the Christian Lebanese Forces in East Beirut during the Lebanese Civil War until 1990. In Vogelzang’s event, the participants inscribed their bowls with a personal story. “Everybody was talking to each other,” she says. “It really bonded them together. The green line is still a very negative thing, we wanted to fill it with positive stories.” The bowls were presented to market-goers, who responded enthusiastically, eating them with the staple accompaniments of ricotta and cedar honey. This wasn’t a spectator sport – everyone was involved, and the barrier was broken down, literally consumed. “No matter what political background you have – food is the thing that combines us. We all have to eat.”

Vogelzang likes to concentrate her work on difficult emotions. She prefers funerals to weddings “because painful emotions are more interesting to combine with food”, and says tears are her biggest compliment. In this respect Vogelzang is using food as a therapeutic tool. It’s in this area that her work has its most powerful practical applications. For instance, obese children know that they shouldn’t be eating fast food, but don’t have happy feelings about healthy food. So she designed an entirely new way for them to look at eating based on Leonardo Da Vinci’s colour wheel, in which different colours tally with different emotional states – blue means tired, orange is happy and red equals energy. Children would pick how they wanted to feel, and eat the food of that colour. The scheme ran out of money before it could be piloted, but Vogelzang has just met with a hospital to put some of her ideas into practice.

However, it’s not about finding a “cure”. “I’m curious about food and what it does to people,” she says. “My aim is to explore it, rather than use it. I don’t know enough about it to use it – I’m a temporary expert.” Vogelzang finishes off her whisky. It’s been a long day for her and her staff. She currently has around 25 people working for her – including a cook and a business manager. But she’s not interested in expanding the Proef franchise – she’s actually considering closing the cafe down. It’s the social projects that she’s finding interesting – “that’s the focus point for me,” she says. “Sometimes I stumble across something that could be curing. It’s not my aim, but maybe it could be nice.”

Chef Michael Smith helps Vogelzang decorate the table top with forgotten vegetables for the March 2008 dinner

The first course was a mackerel and a small cold onion

For a pre-dinner snack, small coloured doughs were baked on angelpoise lamps attached to a wooden tree installation (designed around the concept of photosynthesis)

Taste of Beirut, 2008. A “green line” of bread bowls was lined up at the farmer’s market in Beirut. The handmade bowls were served to market-goers with cedar honey (referencing the Cedars of Lebanon) and ricotta (made from yoghurt – from which the country “land of yoghurt” got its name)

The National Tapwatertasting, 2007. Using an empty reservoir basin Vogelzang orchestrated a tasting of the Netherlands’ 12 tap waters – some known to be purer than bottled water

Vogelzang with Arianne the chicken on her head

How to Impress your Children, 2007. Vogelzang’s daughter is taught to like vegetables with carrot “witch fingers”

Stew, 2006 – bread is scooped out to create a pouch for food

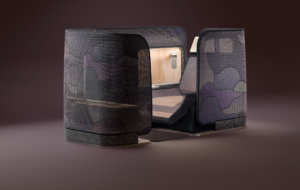

Droog Christmas Dinner, 2006. Dinner guests had to eat their way through a dough tablecloth, cooked using angelpoise lamps, before they could get to the bowls beneath

One of the many experiments Vogelzang is working on for a book

Burns Night for Glenmorangie whisky, 2008. Vogelzang created a dinner using traditional Burns Night ingredients encased in ceramic eggs that had to be broken open

Another Droog Christmas Dinner, 2006. Vogelzang reversed the tablecloth so it went up around guests’ necks rather than falling on their laps

White Funeral Lunch, 1999. Vogelzang made a funeral dinner using white fish, rice paper, potatoes, almonds and other white food Ingmar Swalue

Toothless, 2008. Exceptionally sugary sweets for people who have no teeth