words Justin McGuirk

“I’m the only artist in the world who does things like this,” says Joep van Lieshout. “In a way I’m building a kind of world.”

The only question is, is it a world that anyone would want to live in? The Dutch designer and artist has been describing a series of large-scale installations that he has embarked on involving cages, wooden bunks, silos and large vats with pipes coming out of them, all of which combine to perform a dehumanising cycle of functions from force-feeding and shit extracting to body-part recycling. In short, van Lieshout has taken to designing concentration camps. The works mark a dark and megalomaniacal turn for a man who made his name designing brightly coloured mobile homes.

But van Lieshout is no doom merchant; he is as affable as can be. Thick-armed and barrel-chested, he might be a wrestler if he weren’t dressed in lime green linen. He is sitting in an office he built himself on top of a shipping container on the end of an industrial pier in the port of Rotterdam.

The room is lined with shelves stacked with his exhibition catalogues and various other effects, like an anatomical model of the male reproductive organ and something pink in a box labelled Cyber Pussy. From here van Lieshout presides over what must be the world’s most eccentric design studio.

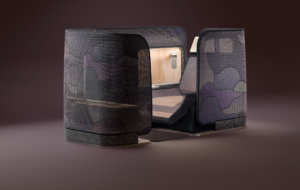

Atelier van Lieshout is a compound of sorts, hidden behind a green wall made of the studio’s trademark fibreglass and topped with barbed wire. The place is littered with van Lieshout’s creations: there are discarded composting toilets in pastel colours, cars sprouting odd fibreglass extensions and faceless mannequins in various positions and states of completion. The workshop itself is in a vast 1920s cotton and spice warehouse whose walls are still dusted with turmeric. Inside it a team of workers is busy sanding down a 50ft-long resin conference table in the shape of an amoeba.

It was at the end of this pier in 2001 that van Lieshout founded the free state of AVL-Ville. This now notorious venture was a year-long experiment in autonomous living – effectively a self-sufficient commune with its own flag, constitution and currency. Van Lieshout and his disciples designed and built everything in it, from the living units to the machine guns. Part art farm and part spectacular publicity stunt, the project was a pregnant piece of post-millennial escapism.

“I think I am a romantic but on the other hand I think I am very well part of our society,” says van Lieshout. “I’m not utopian.” Van Lieshout hates this word, but it is easy to see why people apply it to him. The AVL Ville experiment and even Atelier van Lieshout – where staff share communal meals and where some even live – can be seen as idealistic attempts to shape an alternative environment.

AVL is the kind of place that spawns rumours, some rather far-fetched. According to one that I have heard, the staff have to sleep with each other – a notion that amuses rather than disturbs van Lieshout. “Some people, like interns, live in the containers and mobile homes, and basically it’s like any other company: they fuck together but it’s not a policy.”

Van Lieshout studied sculpture at the Academy of Modern Art in Rotterdam, but he established himself as a cult figure on the edge of Dutch design and architecture at that critical moment in the mid 1990s when the country was leading the world in those disciplines. Like Droog and other key designers of the period, van Lieshout’s creations employed standardised, unfinished materials in inventive ways – multi-gyms made out of scaffolding poles, bars out of shipping containers. The studio produced everything from furniture to moulded room interiors, even designing the toilets for a number of OMA buildings. But while the tendency in Dutch architecture was towards massive housing projects and masterplans and a faith in social cohesion, van Lieshout was designing quirky mobile homes that suggested escape and individualism.

These lurid camper vans, and the Clip-On house extension, spoke of a desire for self-sufficiency, while his Shaker furniture series of the same period emulated the simple, handicraft ethos of the isolationist American religious sect. All of which presents an artistic credo somewhere between DIY and survivalism. At one point in our interview, van Lieshout talks admiringly about the Unabomber – for a time America’s most wanted terrorist – for his “little shack somewhere in the woods” and his “little vegetable garden”.

The answer to why this Waldenesque existence appeals to him can be found in his recent works, which paint a very bleak picture of society.

“This is the biogas installation inside the MAK [Museum of Applied Art, Vienna], and consists of a biogas digester that we designed and developed and which is made for the excrement of a thousand people,” says van Lieshout, explaining a picture on his laptop of a work called The Technocrat. As he clicks through a selection of images, his explanations of the processes at work become a graphic monologue of horrors. “So we have here a big vacuum tank with a thousand hoses … we are collecting shit from the burghers and the gas is used to cook the food for those people … This is the force-feeding … This is the distillery, to produce alcohol which is used to keep them happy or quiet or whatever … there are two hoses: one in the mouth and one in the back … storage of waste liquids that still have a nutritious value … silos …” As he talks, getting up occasionally to fetch one of his hand-drawn plans, what is striking is the emphasis on details and precise measurements. These things aren’t meant to be used, but they are meant to work.

Van Lieshout admits that he has “a love-hate thing” with design. Design comes across as almost a necessary evil in the undertaking of what has become his grand artistic project, which is the creation of his own world, one that both mirrors and parodies the larger one.

The Technocrat has a companion piece called The Disciplinator, which is a cage in which theoretical (and occasionally live) inmates sleep on wooden bunks and undertake the useless job of filing away at tree trunks. It’s a miniature concentration camp. Both pieces purport to demonstrate how easily society’s obsession with order and control, even in supposedly benign systems like recycling, can be taken too far – how extreme rationality becomes insanity. “The title of this one is the Total Faecal Solution,” he continues, pointing to another work on his computer, which involves a series of vats for turning excrement into cooking gas. “So it has very much to do with, for example, the Holocaust.”

All these modular systems and organising principles seem to tap into something very Dutch. In fact, they almost lampoon Dutch sensibleness. The Holocaust, after all, didn’t happen that far away from here. “It’s happening here at the moment,” states van Lieshout with deadpan alarmism, “it’s just that we don’t see it.”

He starts railing against proposals for ID cards and high-tech passports. “Everything is very clean, nobody is killed, but it’s very easy to track down people who do something wrong, and I like to do something wrong. Well, not that I like to do something wrong… but this can go out of hand. Maybe one time you have a fight or a disagreement or you say to a policeman ‘Fuck you’ or whatever, the rest of your life you’re looking at this…” In essence, he is an old fashioned anti-authoritarian.

It is not just insidious social systems that put the fear in him, but also economic ones. His latest work is called The Call Centre, which he describes as “a business plan”. It’s a masterplan for a town of 200,000 people engaged in telemarketing. The town is completely self-sufficient, recycling everything and generating its own energy. And this efficiency extends to the inhabitants, who have targets to meet. “If you drop under a certain level you will be recycled,” he chuckles. “But then, you know, it’s not just that you will be burnt or something but they’ll take your blood, take out your organs. So you could say that to kill one of those persons you could maybe save five other people.” Save them for what, though, is the obvious question.

Van Lieshout produces a spreadsheet on which he has calculated that the plant would generate €7.5bn in profit a year. “You can imagine that if you had maybe five of those call centres you’d become like a really big player on our planet. You could buy Microsoft for example, you could have an army – I think you could really make a very big, scary, dangerous army.”

Van Lieshout has some small experience in warfare, since at AVL Ville he and his disciples created home-made guns and mortars. The exhibited drawings evoked Ikea-style assembly instructions. “I was saying, ‘Okay, you guys out there, you want some power? Buy the drawings and go shoot some people!” He breaks into a laugh and then turns serious again. “No, basically it’s about facilitating other people.”

For van Lieshout, the ordering impulses of society are there to be fought, while the systems of global capitalism are there to be parodied. For him, design and art, or the creative life in general, are a means towards independence and setting one’s own rules. Unusually for a designer, this extends to deliberately exempting himself from the processes of mass production. His romantic faith in making things by hand has led to a fusing of artwork and commodity – essentially, AVL produces utilitarian art. “I don’t use computers to design,” says van Lieshout. “I use computers to calculate how much profit you can make in a concentration camp.”

Another rumour I’ve heard about van Lieshout is that the only book he has ever read is Machiavelli’s The Prince. At the very, least you would expect him to have read some Kafka. “I never read fiction,” he says. “I’m more interested in research into how architecture and design is used to have a goal.” Lately he’s read two biographies of the Nazi architect Albert Speer, and a book that raises a genuine flush of enthusiasm. “I bought this book, it’s about 1,200 pages of Nazi architecture – a guide. Its like 1,200 pages,” he repeats excitedly, “there’s thousands and thousands of buildings built by the Nazis for different goals.”

The man is a bundle of contradictions, or, at least, it’s fair to say that his work plays on oppositions: the rational and the irrational, the good and the bad, the utopian and the dystopian. He can empathise with the cold rationalism of Nazi architecture and yet he will also produce works that are humorous, scatological, sexually liberated and a poke in the eye of middle-class embarrassment. Among these is a series of sculptures of human organs, giant anatomical models of a liver, a penis or a vagina. They are provocative in their bad taste.

“Did you see the Bar Rectum?” asks van Lieshout with a mixture of mischief and pride. This self-explanatory piece is a new installation in the forecourt of Rotterdam’s Boijmans van Beuningen Museum. Somehow, it’s very Dutch. It also adds to the growing sense I am getting that – with the focus on sex and death, the profane and the absurd and imaginatively gruesome punishments – that van Lieshout is a latterday Hieronymous Bosch.

Van Lieshout is one of the few artists or designers with such an obviously moral dimension to his work, ambiguous though it often is. The obvious question to ask a man with his creative ambitions and a secessionist tendency to boot, is how far can he take his vision? If it weren’t for the commercial pressures of having to sell work and sustain such a large studio then, he says, “it would be really fantastic to build this world. Some king or queen should gives us a couple of million a year … that would be the best. They would probably have something fabulous after 20 or 30 years. There’s no place in the whole world that would look like this.”