words Sam Jacob

The pageantry surrounding the funeral of a reality television star laid bare the mechanisms of our manufactured social realm, says Sam Jacob.

As was fitting for Britain’s biggest reality TV star, Jade Goody’s funeral played out publicly, live on Sky News, bookended by OK special issues, pontificated on by commentators. Goody was a modern media persona, famous, famously, for doing nothing apart from being herself in front of cameras. From her appearance in Big Brother through her evolution into celebrity, she projected a peculiar kind of charisma – a sensation of authentic personality. She, among the obvious falsities of celebrity culture, was somehow more real. Through her clumsiness, mistakes, faux pas, Jade became a kind of gonzo-media-democratic figure, representing the lumpen, ill-educated and dispossessed in the pantheon of glossy celebrity.

Authenticity is complicated in the age of reality television. Her ordinariness, multiplied by media saturation, made her extraordinary. Her real-ness was as much manufactured by the media as it was authentic. As in life, so in death. Her death was the ultimate, undeniable moment of the reality concept. Yet even in this moment of truth, complexities of authenticity swirled around her.

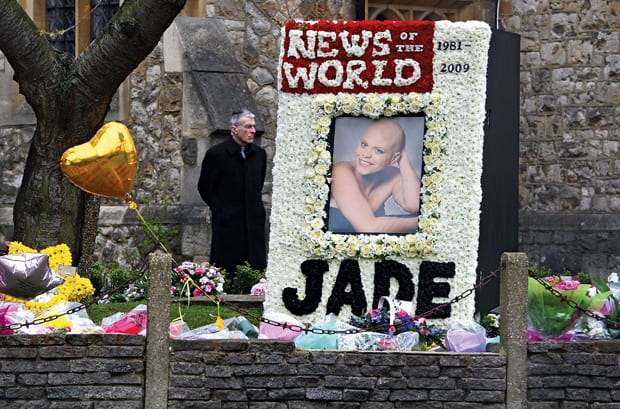

As her white coffin was loaded into the vintage Rolls Royce hearse, paparazzi bulbs flashed. On top of the hearse, a wreath spelled out “Jade” “From” “Bermondsey” in pink carnations. On its side an effigy of a camera was formed out of flowers. Jade-isms adorned the hearse: “East Angula”, a floral jar of Marmite. Outside the church, a front page of the News Of The World in carnations might have been a tribute, an advert or a comment – or perhaps all of these things. The ancient language of flowers mutates into a folk-pop media. Here, wreaths acted like standfirsts and pull-quotes. They were text, image, caption and soundbite. The subtext of the funeralia suggested mourning for the mediated, represented Jade as much as for her as a human being.

As the cortege passed from Bermondsey to Essex, it also traversed a landscape of media and a range of different realities. Along the route, people held signs saying “Goodbye Jade” in felt-tip bubble writing. Well-wishers wore homemade T-shirt tributes, a woman wrote “RIP Jade” on her cheek in eyeliner. Outside the church, big-screen TVs relayed the events to the crowd. Their presence was a form of participation, as if being there somehow made their relationship with Jade real, and allowed their virtual feelings to find physical purchase. In the signs and souvenirs which express a shared emotion – like AIDS ribbons, or tour T-shirts – we see ways of participating, efforts to connect.

We might trace compassionate participation back to Live Aid, or the big-screen public patriotism of Euro ’96, where display became a means of taking part, and Diana’s funeral, which hitched hysterical sentimentalism to a public event. These are moments of collectivism in an era of atomised social relations. The tragedy of the situation is that our normal alienated condition is an effect of the very devices that allow us to participate: the mechanisms of media. This is a simulated collectivism that gives us sensation of participatiing without any traction.

Jade’s funeral exemplifies this condition. Though it feels like a grassroots welling-up of sentiment it is also a synthetic, artificial construct – like those hand-written placards at political rallies that are authored by the singular hand of a campaign staffer. This folk pageantry and mass sentimentality might perversely be a function of detachment.

This twin sensation – true/not true – is at the heart of the Reality phenomenon. In the effort to show reality, fictions emerge. Reality TV is real not because it shows us life transparently, but because it reveals the qualities of the lens through which we see the world.

Media creates a shared public space, or at least a shared environment. The traditional idea of the piazza is now a fizzing, pinging cloud of data. If Venturi argued that we should be at home watching TV in order to experience “the public”, now we might be anywhere. As the ubiquity of traditional media diffuses into multiple channels and formats, it is no longer the medium that creates shared space but the content that binds us: a story, a personality played out multiply and simultaneously.

We seem to be in a realm of the mechano-celeb-horror of JG Ballard’s Atrocity Exhibition. Jade’s body becomes the site of a manufactured public realm. The corpse of a 27-year-old becomes a landscape over which a range of concerns and interests are played out. Born out of media, Jade’s skin seemed to photosynthesise the gaze of the cameras. “I don’t know where I end and you begin” read the old perfume advert – back when perfume was a branch of fashion, not celebrity spin-off – and that might be the real epitaph for Jade and her multiple realities.