words Rick Poynor

This classic call for everyday beauty is as fresh and vital as ever, says Rick Poynor.

Bruno Munari’s Design as Art, first published in English in 1971, has been out of print for much too long and Penguin’s decision to reissue it as a Modern Classic couldn’t be timelier. Inevitably, some elements of this collection of short writings have dated, but Munari’s way of thinking stands revealed – not for the first time – as extraordinarily prescient and relevant to many of the design problems we face today. His playful, inquiring, socially aware intelligence mark him as what we would now call a “critical designer”. The great charm and delicacy of his writing makes the humanity and good sense of his arguments even harder to resist.

By the 1960s, Munari was convinced that design had become the most significant visual art of its time. He had started as an artist himself, joining the Futurists in the late 1920s, and his own transformation into a designer gives his position added authority. Munari wanted to tear down the myth of the star artist who produces work for the intelligentsia. “It must be understood that as long as art stands aside from the problems of life it will only interest a very few people,” he writes. “Culture today is becoming a mass affair, and the artist must step down from his pedestal and be prepared to make a sign for a butcher’s shop (if he knows how to do it).”

Munari shared the Bauhaus ideal that art and life should be fused back together. The designer’s job was to respond to the needs of the time. Art should not be divorced from the everyday, an ideal world where we go to find beauty; visual quality should be part of everyone’s ordinary experience. Only when the objects we use and the places we inhabit have become works of art will life be in balance. Hand in hand with this goes a rejection of the idea of the designer with a personal style, which Munari regarded as a remnant of romanticism and a contradiction in terms.

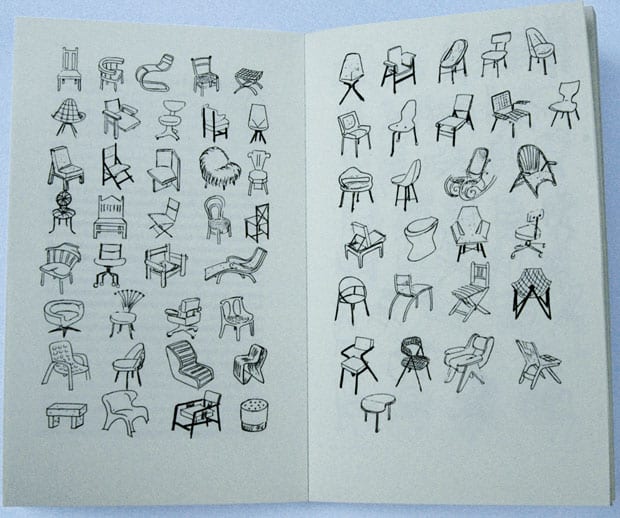

His activities ran from graphic design to industrial design, by way of children’s books, and his observations are similarly elastic – such breadth of thinking is now rare. The book is sprinkled with Munari’s sketches of faces, chairs and letterforms, diagrams of his “useless machines” (aerial mobiles), theoretical reconstructions of imaginary objects, designs for lamps, and photos of his experiments with projected imagery. He points out that the ancient Japanese word for art, asobi, also means game, and this was the way he proceeded, as if playing a game, trying things out to see what would happen. Commentators have pointed out the Zen-like nature of his thinking and his passion for Japanese culture lies behind some of his most absorbing writing, including a lovely essay on the simplicity, lightness and adaptability of a traditional Japanese house. He concludes by contrasting this sarcastically with the uncivilised dirty marble of Italian homes.

Another essay directed at Italian readers begins by appearing to offer advice about knives, forks and spoons to young married people about to equip their kitchens. He runs through three pages of indispensable implements before suggesting, if all this seems a little expensive, a last resort – chopsticks. “Millions of people have been using them for thousands of years. But not us! No! Far too simple.” Fancy goods such as corkscrews like pigs’ tails and ashtrays in the form of little houses provoke similar ironies. Munari is everywhere opposed to excess. “Subtract rather than add,” he advises.

If this makes him sound like a killjoy moralist, he was anything but that. Andrea Branzi has described Munari’s method as a kind of jiu-jitsu, turning an adversary’s force against himself. He was able, notes Branzi, to find drops of goodness in even the driest places. “To do this he does not need to be ‘against’ reality, but ‘within’ it.” This is a gently subversive style of thinking that might still strike a chord with any designer trying to find ways to tilt practice in new directions while maintaining a position of leverage on the inside.

It’s sobering to be reminded that most of these essays were first published in a daily newspaper, Il Giorno. It would be impossible now to find writing this speculative outside the design press. In one of the book’s most inspired mind games, Munari describes an orange, peas and a rose as though they were industrial products. Pursuing the logic of production for purpose – a logic he might seem to condone – he proposes that the rose is “an object without justification, and one moreover that may lead the worker to think futile thoughts. It is, in the last analysis, even immoral.” Impeccable reasoning, absurd conclusion: a perfect illustration of Munari’s mental jiu-jitsu in action.

Design as Art, Bruno Munari, Penguin, £8.99