words William Wiles

There’s a sense of the epochal about China Design Now at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum – with the Beijing Olympics in August, 2008 is China’s year, and there is no better time for a major exhibition on the country’s burgeoning creative industries. The People’s Republic is not the totalitarian state it once was, and the Party’s grip on the minds of its subjects has dramatically loosened since the 1970s. But there is still a tendency in the West to see China in monolithic terms, ignoring the country’s diversity and treating the state and its citizens as essentially the same thing. China Design Now is a useful antidote to this inclination, driving home China’s plurality, as reflected in its creative output.

The exhibition is ambitious to the point of insanity. It focuses on architecture, fashion and graphic design, but also includes film, photography, product and furniture design, youth culture and digital media. It would be a tall order to do justice to all those areas even if one was dealing with a smaller and less important country. You have to admire the chutzpah of the V&A and the show’s curators Zhang Hongxing and Lauren Parker. Inevitably, China Design Now falls short in some categories. But the areas it does well, it does very well.

The space, designed by London architecture practice Tonkin Liu, is structured as a journey up China’s coast, visiting the cities of Shenzhen, Shanghai and Beijing. The Shenzhen: Frontier City section focuses on graphic design, and digital and alternative media. Shanghai: Dream City looks at China’s mushrooming consumer culture, taking in product design and fashion. Beijing: Future City devotes itself to architecture, looking at the mega-projects changing the face of the Olympic city, and some more modest buildings elsewhere in the country.

In terms of design interest, the show starts on a high note. The Shenzhen section is excellent. China’s 3000-year heritage of the written and printed word is unsurpassed – it’s a milieu of incredible richness for modern graphic design. Much of this work, from designers such as Wang Xu, Teddy Ho and Chen Shao-hua, explores Mandarin ideograms, the semi-pictorial system of Chinese writing. The system’s subtleties of meaning – many of these posters are essentially visual puns – might be opaque to a Western audience, but its extraordinary beauty transcends the language barrier. Some of the work, such as the trade directories produced by the Shenzhen Graphic Design Association, inventively combines contemporary design with traditional bookbinding techniques. The highlight is an exhibition catalogue by Guang Yu, in which the artist’s name is spelled out by the thread that binds the pages together.

On to Shanghai and into the night, as China Design Now is (rather unnecessarily) designed as a journey through times of day as well as through cities. This middle section is the weakest of the three, and suffers most from the show’s broad remit. There’s a minimal amount of furniture and product design. At first this feels like a curatorial shortcoming, but in fact it’s probably an accurate reflection of the situation in China, where the country’s gargantuan manufacturing base has not yet spawned much indigenous design in this area.

The rest of the Shanghai exhibit is taken up with fashion and a selection of displays exploring the rise of consumer culture and the aspirations of the growing middle class. These latter inclusions, looking for instance at Thames Town, an ersatz England being built near Shanghai, are interesting enough, but feel like deviations from the show’s “design now” thrust. Maybe its most effective achievement is in mood, conveying the sense of a society that is not only enjoying its first taste of consumerism, but also experiencing its limitations and disappointments for the first time.

And, finally, into the dazzling Beijing dawn, and the Brave New World of the Future City. Except that a lot of it no longer feels very new. Whether by accident or by intent, the architecture section serves as a microcosm of how Chinese architecture is presently treated by the Western media. Hogging the limelight are a handful of huge projects by Western starchitects: Koolhaas’ cubist doughnut, Herzog & de Meuron’s laundry basket, Lord Foster’s airport. The blaze of exploding flashbulbs around these mega-structures almost obscures a large number of smaller projects by emerging Chinese practices: the Apple Elementary School in Tibet by Wang Hui (icon 059), the Vinxu Museum by the China Architecture Design and Research Group, the Commune by the Great Wall by Atelier FCJZ and Ma Qingyun’s Father’s House, to name just some of the best examples. These Chinese architects are producing excellent work, and it is characterised by dignity, sober formality, material honesty and a sense of lasting value. The Western showpieces are billboards advertising a new China, and are meant to grab the eye, but they can distract from the fact that the domestic league of the profession is strong and getting stronger.

China’s growing global power makes many people in the West nervous, even gloomy. In this context, China Design Now performs an incredibly valuable role: it show us the optimism and dynamism of the country’s new creative class, and the excitement that they are creating. The optimism is contagious, and gives us a view of China beyond the blue-tracksuited version that dominates the media.

images MADA; Zhan Jin

top image Kan Tai-Keung’s poster series for the Communication exhibition, 1996

Kan Tai-Keung’s poster series for the Communication exhibition, 1996

Kan Tai-Keung’s poster series for the Communication exhibition, 1996

Wang Xu’s Chinese Characters poster series for the Taiwan Image exhibition, 1995

Wang Xu’s Chinese Characters poster series for the Taiwan Image exhibition, 1995

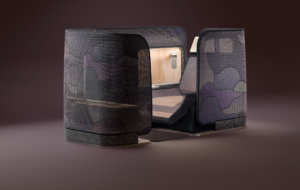

Ma Qingyun/MADA’s Father’s House, 2002

JiJi’s Hi Panda, 2006