words Alex Wiltshire

Bill Mitchell, head of Media Arts & Sciences at the MIT Media Lab, was in London recently promoting his new book, Me++: The Cyborg Self and the Networked City. Icon met him to talk about his ideas on how virtual reality has been superseded by “augmented reality”, in which wireless devices, such as mobile phones and laptops, allow people to interact with more freedom across ever larger networks in the physical world.

What does the speed at which technology is changing at the moment mean for designers?

It’s the business of designers to be able to move into a situation and learn very quickly and make some sense of it. It’s fundamentally what designers are all about. I think specifically in architecture at the moment wireless networking is really challenging traditional ideas of organising a building around a set of spaces that have particular, highly specialised uses. We’re moving to a situation where you try to create very flexible spaces that can be appropriated to a lot of different uses depending on the functionality their users bring to them.

So users bring the technology with them?

It’s interesting; the more genuinely high-tech spaces are becoming, the less they look like what people think of as high-tech, because the really good technology disappears into your pocket, disappears into the woodwork, so you can design these spaces around very basic human things like social interaction. Right through the 20th century, spaces were largely designed around specialised technology. With miniaturised technology we’re able to move to the element of what you might think of as very basic pre-industrial concerns.

In the book you say that miniaturised technology forces designers to work on many different scales in traditionally disparate disciplines. As an academic, how do you teach people to do this?

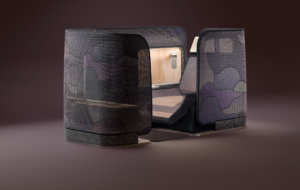

You can’t use the old models that still prevail in a lot of academia in which you accumulate this stock of intellectual capital that you then use for a career. What you have to have now is this capacity for fast learning, for really rapidly moving to new areas and using the resources that are available, and bringing yourself really quickly up to speed. As an example, the latest project I’ve been working on with Frank Gehry is a concept car for General Motors. Neither Frank nor I knew anything about cars before this project. We put together a team of graduate students from a lot of different areas and using all the information resources out there, like Google, what we’re able to do is ask the dumb, basic questions in a very direct kind of way, and very, very quickly learn within a very unconventional framework and then move into a new design domain. Often traditional rofessional categories just don’t make any sense any more.

What’s this car all about?

We’ve been working on it for a couple of months. We’re thinking of it as a car that forms an interface with the resources of the city. It’s as much electronics and software as it is transportation. The idea is for the car to have the sort of intelligence of a taxi driver if you like – knowing the city, knowing what you’re trying to accomplish, and being able to form a relationship between the two.

One of the biggest symbols of this new functionality in the book is the mobile phone. What does the mobile phone mean for you personally?

I use it minimally, frankly. I carry one around, it’s right here in my pocket, but you’ll notice it’s turned off and that’s what I usually do. What’s much more important to me is a wireless laptop computer. You can hook up to your email, to the web and all that sort of stuff anywhere there’s a wi-fi network, and that’s a very, very powerful thing.

You talk about how mobile phones have become more than just phones…

They used to be simple telephones, then they got text capabilities, now they’re getting cameras. Pretty soon the differences between these things and a personal digital assistant disappears, and they become location-aware and a whole load of other things. It’s not just wirelessness, it’s the intersection of wirelessness and miniaturisation, so you can pack a lot of functionality into very small portable packages, then combine them with wireless networking.

What are the effects of these multiple functionalities?

New combinations of functions have very interesting social effects. It’s been obvious for a long time that you could put a digital camera together with a phone. Finally it happened and socially and culturally it’s taken off in an extraordinary way. It opens up real new social and cultural possibilities. Take a simple example – it has revolutionised construction sites. The whole business of being able to put image and voice together in new ways amazingly quickly created a whole bunch of social customs and ways of interacting. Your face can be on a phone on the other side of the world without you knowing it, and that new combination is a very significant thing. Right now, you have those two things side by side in your bag – a phone and a digital camera – but putting them together opens up something fundamentally new.

Me++: The Cyborg Self and the Networked City, MIT Press, £18.95