|

Villa Nurbs is a mythical beast. Drawings and models of it have been circulating for years, embedding it in the pantheon of possible futures. The house itself, however, has been developing in human time, almost imperceptibly slowly: a growth spurt here, a sprout of facade there. It has become a cult object, so that whenever an architect passes through Barcelona – Winy Maas, Kengo Kuma, Bjarke Ingels – they say, “Take me to Villa Nurbs”. I first encountered the model seven years ago at the São Paulo Biennale and assumed that, as is often the case with such models, it would never be built. However, I knew that if it ever did materialise, I would write about it. But things don’t always transpire as you imagine them. Today, I am standing 20m from the house. Having flown to Barcelona and driven an hour and a half north to Empuriabrava, I have arrived at an opaque metal fence. The owner of Villa Nurbs will not let me onto the property. I spent this morning in Barcelona with the house’s architect, Enric Ruiz-Geli. His practice, Cloud 9, has recently built an office block in the city, a lime green high-tech structure with a facade of ETFE pillows filled with smoke. It looks like the Eden Centre being fed through a grinder, and it proves, if nothing else, that Ruiz-Geli is determined to test unconventional ideas. In fact, the practice is entirely structured around it. Cloud 9 makes most of its money by producing patents that it shares with a small group of investor clients. It’s an ingenious model for an architect’s business, and places Ruiz-Geli in the romantic role of the inventor-architect, a latter-day Buckminster Fuller – he even has one of Bucky’s own patents framed on the office wall. Ruiz-Geli, 42, is a product of what he calls “the Olympics factory”, taught by the generation that revived Barcelona in 1992. But he was always somewhat ambivalent about architecture, studying stage design alongside it. After graduating, he was only one month into Columbia University’s Advanced Design Studio when he dropped out and went to work for the legendary theatre director Robert Wilson. This background in stage design is key to understanding Ruiz-Geli’s work. He wants to translate the “black box” of the theatre – a world of atmospheric effects instantly transformed by light and smoke – into architecture. The irony is that eight years into the Villa Nurbs commission, with the building still inching along, his experimental approach has taken architecture’s inherent slowness to extremes.

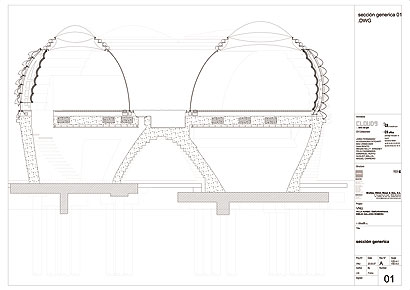

The bespoke Corian facade panels The beginnings were not promising: some restaurateur friends of Ruiz-Geli’s mother wanted a new house. Since Ruiz-Geli was only interested in international competitions, he hoped to deter his potential clients by showing up with a series of photographs of melting ice blocks and asking them to choose which one they wanted to use as a model. It was the dawning of an opportunity. Clients (pointing to a cluster of ice nodules) We want that one. It certainly was, a chance to treat a house as a laboratory. The original idea was for a series of separate pavilions, but as the design evolved these were all amalgamated into one structure organised around a central swimming pool. The result is a blob on legs. It has a heavy concrete base but it gets lighter as it rises towards a roof of ETFE pillows. These employ a system of opening and closing layers that insulate the interior – just one of the six Cloud 9 patents embedded in the house, along with a translucent concrete that allows you to text message your guests on the front door. There are no standard parts, everything in this house is bespoke: the cable system holding together the concrete structure, the car body-like steel frame, each Corian facade panel, every single ceramic tile, every window, the pool and soon the furniture. Therein lies the particular dream that this house represents: a future of mass-customised living. Now that everything can be cut and shaped on CNC milling machines, all you have to do is send your digital files off to their respective workshops. Except it could never be that simple, could it? That’s why the windows alone took nearly two years to manufacture, while the glass walls around the pool – each of which is unique and has an awkward double curvature – broke several times before successfully being installed. No wonder this is taking so long. Critic How will you achieve speed without standardisation Villa Nurbs was one of the first of the digital houses, in the same generation as Greg Lynn’s blobs of the late 1990s. Even the name references that bygone thrill with digital tools and their potential to generate form: a NURBS (or non-uniform rational Bezier spline) is the most complex kind of smooth surface you can create in computer modelling. The form is almost prosaic by the standard of today’s digiterati. It is the strange fate of this house that, though unfinished, it is already a period piece. Like much digital architecture, Villa Nurbs is scaleless since it has no outward relationship to the human body. The interior – and here, from behind the fence, I have to go on photographs and drawings – is more or less a continuous space, except for a separate spa area. There are no corners, but rather the seamless flow of surfaces that was Antoni Gaudi’s bequest to Catalan architecture. The only walls are the curvaceous glass ones around the central pool. Etched with a blue dye by artist Vicky Colombet, they will presumably radiate a blue light. The interior continues down into the geological concrete legs, where there are two cave-like spaces that will be especially useful in the heat of summer, in conjunction with the dramatic 26m cantilever intended as the roof of an outdoor room. Certainly, with its hearth-like pool, this is an extremely introverted house, perhaps the perfect interpretation of the future suburban life. More than anything it reminds me of Frederick Kiesler’s Endless House of the 1950s, a fluid space encased in a Surrealist egg. Interestingly, Kiesler was another architect turned stage designer. Both he and Ruiz-Geli treat the house like a theatre: a protective womb in which a family can play out life’s daily dramas and rituals. Critic How will a family with teenage kids cope with one fluid space? Inside this sanctum will be a world of ubiquitous technology, but one swept clean of technical clutter. With one decisive gesture, Ruiz-Geli removed all the machinery that permeates the modern home into a solar-powered shed in the garden. The motors running the fridge, the kitchen extractor fan and even the vacuum cleaner will be housed in that shed, connected to the house by underground pipes. With the “hardware” removed to this centralised engine room, the house is left to be pure interface. There won’t even be any light switches, just sensors. Ruiz-Geli likens the shed to the astronaut’s backpack, a life-support system removing the whir of technology to preserve the silence of space.As in the theatre, gadgetry clears the stage for the smooth performance of everyday life. All of this has the ring of a Jacques Tati film, like the ludicrous modern house in Mon Oncle, with the latest in dysfunctional mod cons. It’s almost nostalgic for bygone futures. Think of Suuronen’s Futuro House or Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion House and their dreams of space age living. Just as they were distinctly vehicular, Ruiz Geli describes Villa Nurbs as “a bridge between car and boat”. But its predecessors never caught on. Perhaps it’s because designing a house like a car dooms it to rapid obsolescence. What if we want to change the fridge or the vacuum cleaner? The French philosopher Paul Virilio has written an essay about Villa Nurbs in which he describes it as a “cyber bunker”. Enric emailed it to me – in Spanish – but I can guess what it says: that this house is an incubator, a life-support machine for keeping humanity alive through the dirty-bomb fallout of the consummated War on Terror. Such is the future that Virilio trades in. I may not have made it inside the bunker, but it was crucial to experience the context in which it sits. The house’s impact on the surroundings hits you like a groin shot. It’s the spectre at the feast. Empuriabrava, best known for Ferran Adria’s El Bulli restaurant, is a holiday playground beloved of French, German and Russian second-homers. The former wetland has been turned into a Disneyworld of pastiche hacienda-style houses with towers, each with its own yacht or speedboat moored on its adjacent canal. “Not a dream environment”, says Ruiz-Geli. “But we are not interested in dream environments, we are interested in doing architecture as a positive virus in a perverse Disney context. Our strategy here is: we are Tim Burton and you are Disney; we come to you to create monsters inside your system.”

The future used to be light and smooth. The future was a germ-free clean-room. Futurists today talk about contaminating and infecting. They create hybrids and mutants. To Buckminster Fuller we were all astronauts, to Ruiz-Geli we are Edward Scissorhands. Amid these kitsch white villas, Nurbs plays the outsider with aloof ugliness, like the bastard child of a fly and a Fabergé egg. It may be a blob, incubated in the floating space of the computer screen, but those black ceramic tiles give it a distinctly Spanish sensibility. Created by artist Frederic Amat, they’re like dragon scales. It seems ironic that the craft aspect contributes more to the building’s monstrousness than its alien-style digital modelling. But, in this Floridian setting, it is the house that seems sane and the conformity around it that is monstrous. Everything about this project is incongruous. Not just the context but also the clients. Their restaurant, where I ate calamari and grilled octopus, has folksy timbered ceilings and quaint wooden tables. They do not seem like patrons of futuristic architecture. They did, however, display the bloody-mindedness it takes to be a client of the avant-garde. Wandering into what is clearly a tense relationship, I became a pawn, played by the clients against their architect’s desire to publish his work. Two years is a long time to wait for windows, and they are clearly tiring of the constant interest in their unfinished house. Critic But I flew all the way from London. The message was passed on to Ruiz-Geli, who promptly called me. Critic They didn’t let me in.

The house is organised around an open swimming pool with ETFE pillows for a roof |

Image Luis Ros

Words Justin McGuirk |

|

|

||

|

No Entrar (image: Justin McGuirk) |

||